By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

On April 22, Chris Newlands reported in inews on the release of Google UK’s 2020 financials, noting that it reported £1800 million in revenue and £225 million in profits. This report also noted an often-heard complaint with regards to Google’s transfer pricing:

Google’s UK operation is primarily used as the marketing and sales division of its European operation, which is headquartered in Dublin, where taxes are lower. The Government has attempted to crack down on the use of profits and cash being shifted to countries with lower tax levels, and has introduced a 2 per cent digital service tax.

A Google spokesperson offered the following reply:

Our global effective income tax rate over the past decade has exceeded 20 per cent of our profits, in line with average statutory tax rates. Approximately 80 per cent of that tax has been due in the US, where Google was founded and where most of our products are developed.

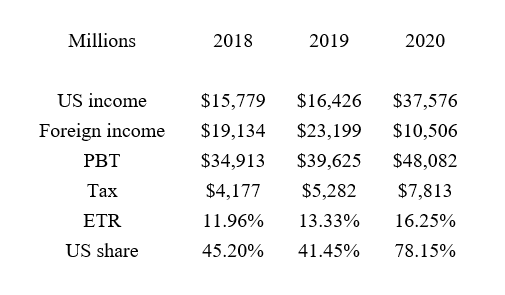

Google’s 10-K filing for fiscal year ended December 31, 2020, offers insights into these apparently contradictory statements. Table 1 shows profits before taxes (PBT) and how these profits were allocated between US income versus foreign income over the 2018 to 2020.

Table 1 also shows worldwide income taxes. The effective tax rate (ETR) is the ratio of worldwide income taxes to worldwide income. ETR was less than 12 percent in 2018, 13.33 percent in 2019, and 16.25 percent.

Table 1: Key Income Tax Information

The share of income sourced in the US was less than 46 percent in 2018 and 2019, even though 46 percent of worldwide sales were to US customers. This share rose to over 78 percent in 2020. The 10-K filing noted:

Our effective tax rate for 2018 and 2019 was affected significantly by earnings realized in foreign jurisdictions with statutory tax rates lower than the federal statutory tax rate because substantially all of the income from foreign operations was earned by an Irish subsidiary. As of December 31, 2019, we have simplified our corporate legal entity structure and now license intellectual property from the US that was previously licensed from Bermuda resulting in an increase in the portion of our income earned in the US.

Before 2020, the provision of income taxation showed a significant benefit from “foreign income taxed at different rates.” While this benefit was very modest in 2020, a significant benefit was received from a foreign-derived intangible income deduction.

One of the goals of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act was to encourage US-based multinationals to relocate the ownership of intangible assets from foreign tax havens to the US by granting a 13.125 percent tax rate to any foreign-derived intangible income.

While Google had located the foreign rights to its intangible assets to the classic Double Irish Dutch Sandwich structure, this structure often has an Irish affiliate acting as the distributor for foreign operations with the assistance of related party commission agents such as the UK subsidiary. The Irish affiliate would, in turn, license intangible assets from a Bermuda affiliate.

Google’s 2020 structure reassigned the foreign rights for its intangible assets to the US parent, which has resulted in a large increase in the US share of worldwide income. While intangible profits faced no Bermuda taxes under the original structure, the effective tax rate for 2020 was 13.125 percent. As such, the restructuring increased Google’s effective tax rate by a modest amount.

Google UK’s transfer pricing

The UK tax base is not affected by whether the Irish affiliate pays intercompany royalties to the US parent or the Bermuda affiliate. The transfer pricing between the UK and Irish affiliates has been controversial for several years.

When the UK government introduced its diverted profits tax in 2015, it was dubbed the Google tax. Saumyanil Deb and I discussed a possible alternative approach to the transfer pricing for the UK affiliate of Google (“The Google Tax: Transfer Pricing or Formulary Apportionment?”, Journal of International Taxation, June 2015).

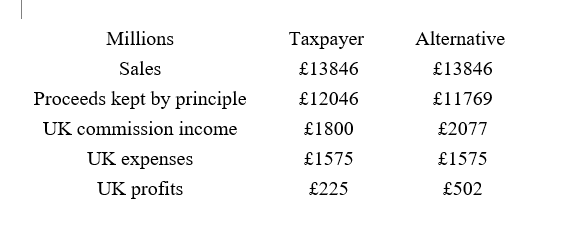

The £1800 million in revenue recorded on the financial accounts of the UK affiliate represents intercompany commission payments from the Irish principle.

Google sales in the UK have tended to be 10 percent of worldwide sales, so they were likely $18 billion in 2020 since worldwide sales exceeded $180 billion. Since the exchange rate for 2020 was $1.3/£, the Irish affiliate received £13,846 million in customer sales, remitting 13 percent of these sales to the UK affiliate in the form of intercompany commission payments.

UK expenses represent 11.375 percent of sales, so its operating profits present 1.625 percent of sales or a 14.28 percent markup over expenses. This intercompany compensation is reasonable for a limited function commission agent.

UK expenses represent 11.375 percent of sales, so its operating profits present 1.625 percent of sales or a 14.28 percent markup over expenses. This intercompany compensation is reasonable for a limited function commission agent.

Table 2 also considers an alternative transfer pricing policy where the UK commission rate is 15 percent. Under this alternative intercompany policy, operating profits represent 3.625 percent of sales or a 31.87 percent markup over expenses.

Table 2: Two Alternative Commission Rates for Google UK

Deb and I contrasted the implication of a commission agent structure versus a structure that converted the UK affiliate to a distribution affiliate.

The profits for a distribution affiliate would exceed the profits for a commission agent under arm’s length pricing by the appropriate return to any working capital held by the distribution affiliate. Working capital represents inventories plus trade receivables net of trade payables. Google’s working capital represents less than 15 percent of sales.

Under any reasonable estimate of the routine return for distribution, the alternative transfer pricing policy would generate a more than generous return for the UK affiliate.

Tax authorities in Australia, New Zealand, and South Korea are also scrutinizing the transfer pricing for distribution affiliates of hi-tech multinationals. In my recent Edgarstat blog post (“Comparability in Benchmarking Hi-Tech Distribution Affiliates”, February 8, 2021), I note a very aggressive transfer pricing challenge by New Zealand Inland Revenue with respect to Oracle’s distribution affiliate.

While part of these controversies may involve how to estimate the routine returns for sales affiliates, the aggressive stances of tax authorities can be seen as attempts to capture a portion of intangible profits as belonging to the sales affiliate.

In the case of Google UK, the debate over how to allocate intangible profits used to be a battle between the UK tax authority versus sourcing such profits in a tax haven. With its restructuring in 2020, the battle over the allocation of intangible profits is now a double tax issue between the IRS and the UK tax authority.

Be the first to comment