By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

The General Court of the European Union’s ruling on July 14 declining to annul the European Commission’s launch of a state aid investigation regarding Nike’s transfer pricing arrangement with the Netherlands hints at some of the issues involved in the underlying transfer pricing dispute. Combining this information with Nike’s public financials creates a picture of the dispute and highlights parallels with current pending US litigation.

General Court’s ruling

The General Court of the European Union on July 14 accepted the assessment of the European Commission with respect to intercompany royalties paid by Nike’s Netherlands distribution affiliates. Nike requested that the European Commission’s ruling be annulled, but the General Court agreed that the intercompany royalties agreed to in various Dutch Advance Pricing Agreements (APAs) left these distribution affiliates with less profits than would have occurred under arm’s length pricing.

Nike designs, markets, and sells athletic footwear and apparel, relying on third party contract suppliers to produce their products. For the three-year period ended May 31, 2020, its worldwide sales have averaged almost $38 billion per year with 26 percent of those sales being to European, Middle Eastern, and African (EMEA) customers. Nike European Operations Netherlands BV is the EMEA distribution affiliate for legacy Nike products, while Converse Netherlands BV is the EMEA distribution affiliate for Converse products.

The General Court ruling noted a series of APAs between these two affiliates and the intangible holding affiliates that were designed to leave these affiliates with operating margins between 2 percent and 5 percent. The agreements also noted that the intercompany royalty payments could range between 5 percent and 20 percent of sales.

The General Court ruling provided no other financial data.

Illustrative allocation of income

Over the three-year period ending May 31, 2020, the financial filings for Nike note that its cost of products represent 56 percent of sales, while its total operating expenses represent 33 percent of sales. As such, its operating profits represent 11 percent of sales. The allocation of these profits between the distribution affiliates and the intangible holding affiliates depend on Nike’s intercompany pricing policies.

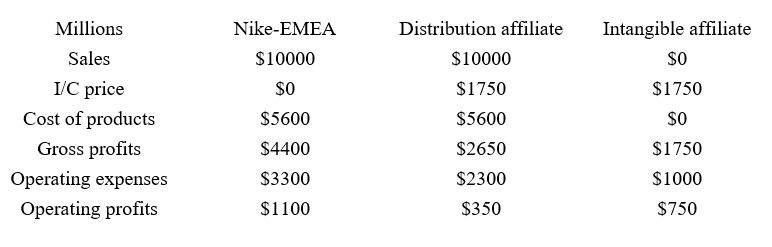

The following table illustrates the allocation of income under one possible set of transfer pricing policies. The table assumes EMEA sales of USD 10 billion, which are booked by the distribution affiliate and cost of products equal to USD 5.6 billion, which is incurred by the distribution affiliate. Overall gross profits equal USD 4.4 billion, while total operating expenses equal USD 3.3 billion. The distribution affiliate incurs USD 2.3 billion in selling expenses, while the intangible affiliate incurs USD 1 billion in design and marketing expenses.

The key intercompany (I/C) price is a USD 1.75 billion payment by the distribution affiliate to the intangible affiliate to cover the latter’s expenses and provide profits for the intangible asset affiliate of USD 750 million. Under this intercompany pricing policy, the distribution affiliate’s gross margin is 26.5 percent, and its operating margin equals 3.5 percent.

Nike EMEA Transfer Pricing and Allocation of Income

These transfer pricing policies have resulted in more than two-thirds of consolidated EMEA profits being sourced to the intangible asset affiliates. The Dutch authorities agreed to having its tax base be limited to only 3.5 percent of sales through the APAs.

Transfer pricing method

Multinationals often justify such limited profits sourced to the distribution affiliate with a transfer pricing report based on the Transactional Net Margin Method (TNMM), which is based on several key assumptions. TNMM reports often assert that all intangible assets are owned by the foreign intangible asset affiliate with the local distribution affiliate performing only routine functions and limited tangible assets. A 3.5 percent operating margin represents only a 15 percent markup over the operating expenses borne by the distribution affiliate. This modest markup would be compared to the profitability of third-party distributors that are deemed to be comparable to the distribution affiliate.

The European Commission asserted that the profitability of the Dutch distribution affiliate was below what would have been expected under arm’s length pricing. The General Court ruling did not detail the reasons for this assertion. If the general premises of TNMM were accepted, another set of alleged comparable distributors would likely suggest only a modest increase in the operating margin unless a claim that the distribution affiliate was asset-intensive.

If the European Commission asserted that the distribution affiliate-owned a portion of the valuable intangible assets, then the premises of TNMM would be challenged. A residual profit split analysis could be used to assert a significantly higher operating margin.

US litigation parallels

This debate between TNMM and the residual profit split approach is also at the heart of the debate in two important US litigations – one involving royalties paid by Coca-Cola’s foreign affiliates to the US parent and the other involving royalties paid by Medtronic’s Puerto Rican affiliate to the US parent. In both litigations, the IRS argued for higher royalty rates using the logic of TNMM, which is also known as the Comparable Profits Method. The taxpayer on the other hand is arguing that the licensee affiliate deserves a share of residual profits.

Before the passage of the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA) in the US, Nike sourced the profits from foreign-owned intangible assets in Bermuda tax haven affiliates. The European Commission’s State Aid claim was based on this shifting of profits to tax havens. TCJA included a provision for foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) to face a tax rate of only 13.125 percent if the US parent owns the intangible assets. Nike’s 10-K filing for fiscal year ended May 31, 2020, notes:

The foreign-derived intangible income benefit reflects U.S. tax benefits introduced by the Tax Act for companies serving foreign markets. This benefit became available to the Company as a result of a restructuring of its intellectual property interests.

For this fiscal year, the vast majority of Nike’s income was sourced to the US parent as the parent-owned all of the worldwide intangible assets. Nike received significant tax benefits from the FDII provision. For its latest fiscal year and going forward any claim by foreign tax authorities that the intercompany royalties are excessive becomes a double tax issue between the foreign tax authorities and the IRS.

Be the first to comment