By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

Medical equipment company ResMed has reached a settlement with the Australian Tax Office (ATO) for USD 381.7 million in additional taxes in connection with an ATO audit over certain transfer pricing issues between the company’s Australian affiliate and its Singapore affiliate, according to the company’s most recent 10-Q filing released October 28.

Based on a review of ResMed’s previous 10-K filings, we suggest that the transfer pricing issue – which has not been disclosed in the various press accounts – may have been an intercompany royalty rate dispute similar to what the US Internal Revenue Service (IRS) raised in the Medtronic and Guidant cases.

This discussion presents the history of ResMed’s operations as a prelude to a reasonable financial model for its intercompany pricing issues.

ResMed’s operations

ResMed Holdings Limited began in 1989 as an Australian company that acquired the Baxter Center for Medical Research Pty Limited, which owned the rights to certain technology relating to a treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. ResMed Inc., a Delaware corporation, was formed in March 1994 as the ultimate holding company for its operating subsidiaries.

For its first 20 years, the Australian operations owned all product and process intangibles and conducted all manufacturing activities. The US parent and other affiliates acted as distributors of its products in the Americas, Europe, and Asia. ResMed continued to update its product intangibles and expanded its product offerings as well as grow its customer base reaching sales near USD 3 billion per year in the two years ended June 30, 2021.

ResMed opened production facilities in Tuas, Singapore, and Johor Bahru, Malaysia. Both nations provided tax holidays for these affiliates. The manufacturing consists of specialist component production, as well as assembly and testing of its devices, masks, and accessories. The numerous raw materials, parts, and components, including uniquely configured components, that are purchased for assembly of its therapeutic and diagnostic sleep disorder products are sourced from multiple third-party vendors.

An illustrative transfer pricing model

ResMed’s operating profits have been approximately USD 900 million per year or 30 percent of sales, as its cost of goods sold have been approximately 40 percent of sales and operating expenses have been approximately 30 percent of sales. These operating expenses consist of research and development (R&D) expenses near 7 percent of sales and selling expenses near 23 percent of sales.

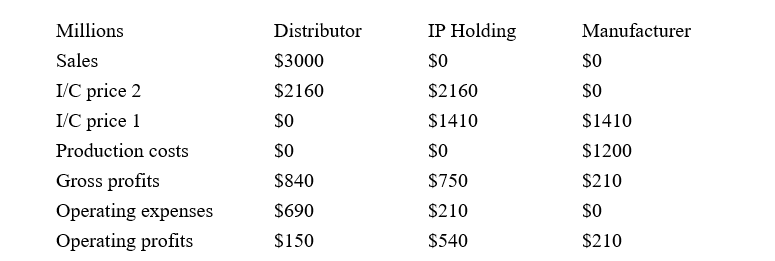

The following table illustrates a transfer pricing structure that assumes that manufacturing affiliates act as contract manufacturing affiliates for an intangible holding affiliate, which sells the finished products to distribution affiliates. For every USD 100 in customer sales, our illustration assumes the manufacturer incurs USD 40 in production costs and sells the product to the intellectual property (IP) holding affiliate for USD 47 (I/C price 1). The IP holding affiliate in turn sells the product to the distributors for USD 72 (I/C price 2). The IP holding affiliate retains USD 25 in gross profits but incurs USD 7 in R&D expenses. The distributor is afforded a 28 percent gross margin and incurs operating expenses equal to 23 percent of sales. Under this transfer pricing policy, the distributor’s operating margin is equal to 5 percent for total operating profits or USD 150 million. The manufacturer’s profits represent 7 percent of customer sales or USD 210 million. The IP holding affiliate’s operating profits represent 18 percent of sales or USD 540 million.

Simple transfer pricing illustration

This simple illustration differs from the actual ResMed operations in several important ways. While the illustration assumes a single manufacturing affiliate, ResMed’s manufacturing operations span several nations, including Australia, Malaysia, and Singapore. It is also possible that the Singapore affiliate sells products directly to the distribution affiliates.

If the Singapore affiliate sells products to the distribution affiliates for 72 percent of customer revenue and neither incurred R&D expenses nor intercompany royalties, its operating profits would be 25 percent of sales, leaving the IP holding affiliate with operating losses equal to its R&D expenses. Clearly, an intercompany royalty would be due from the Singapore affiliate to the owner of intangible assets. The issue becomes what should be the intercompany royalty rate.

The US IRS approach in similar cases such as Guidant and Medtronic has been to assert applications of the Comparable Profits Method (CPM), which increases the royalty rate to capture all operating profits beyond a routine return to distribution and a routine return to contract manufacturing. In our ResMed illustration, CPM would suggest that the intercompany royalty rate should be 25 percent. In my critique of the IRS use of CPM in the Medtronic litigation, I noted:

the Puerto Rican affiliate deserved much more than a routine return for two reasons:

-

- Possible ownership of some of the valuable intangible assets.

- Reward for licensee risk-taking.

(“Medtronic’s Intercompany Royalty Rate: Bad CUT or Misleading CPM?”, Journal of International Taxation, February 2019.)

The Singapore affiliate would likely deserve a share of residual profits for several reasons, including a premium for bearing licensee risks, as well as the possible ownership for intangibles, including not only process intangibles but also any product intangibles it may create by incurring ongoing R&D.

The available public information does not disclose either the initial intercompany royalty rate or the eventual royalty rate implied by the settlement with the ATO. The role in ResMed’s manufacturing played by this Singapore affiliate has grown over time so what represents an arm’s length royalty rate remains an important issue. The issues in the US controversy over what represents an arm’s length royalty rate for medical device multinationals may be relevant for this Australian transfer pricing issue.

Be the first to comment