By Dr. Harold McClure, New York City

The Canada Revenue Agency filed an appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada on October 30, seeking to overturn its loss in the Federal Court of Appeal in its transfer pricing dispute with Cameco, as reported by Warren Novis in his recent MNE Tax article.

At issue is the Canadian parent’s transactions with its Swiss subsidiary. In particular, the Canadian tax authority disputes an intercompany contract that specified that the Swiss affiliate would pay the Canadian mining affiliate USD10 per pound for uranium for eight years beginning in 1999.

The USD10 per pound price set under this intercompany agreement was the lowest price paid for uranium production globally in 2003, 2005, and 2006, Cameco’s tax years at issue.

The Canada Revenue Agency’s attempt to recharacterize the intercompany transaction has failed so far. While it is not known on what basis it has appealed to the Supreme Court, a close look reveals that the tax agency may have an argument that the economics do not necessarily support Cameco’s USD10 per pound intercompany price.

Uranium transfer pricing

In 1999, Cameco established its Swiss affiliate to market uranium produced by its mines as well as to purchase the uranium that Russia had formerly used in its nuclear arsenal for distribution.

During the early years of the intercompany arrangement, uranium prices fell below USD10 per pound as Russian inventory sales dominated the market. In 2003 and 2004, uranium prices rose, with the average price over the 1999 to 2004 period being USD11 per pound.

Uranium prices continued to rise, averaging USD27.93 per pound in 2006 and USD47.68 per pound in 2006. As such, the Swiss affiliate received substantial profits under the intercompany pricing policy, while the Canadian affiliates earned very little profit.

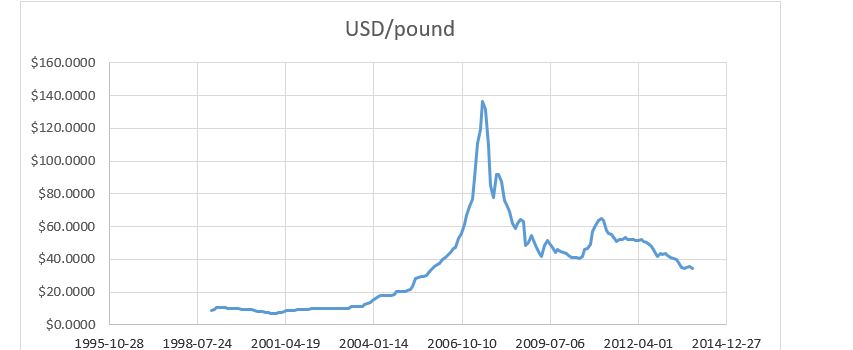

The following table illustrates the volatility of uranium prices during the years at issue in Cameco and beyond.

Uranium prices: 1999 to 2013

The Canada Revenue Agency challenged Cameco’s intercompany pricing arrangement using several approaches to argue that most of the Swiss-based profits should represent Canadian taxable income.

The Canada Revenue Agency’s argument was, basically, that the Swiss affiliate should be seen as a mere distributor that deserved a modest gross margin.

Gross margin for routine distribution

One of the Canada Revenue Agency’s expert witnesses testified that the Swiss affiliate’s gross margin should be only 3.5 percent of sales, which represents a reasonable routine to distribution since the marketing costs of the Swiss affiliate, including the efforts of a US sales affiliate, represented 2.5 percent of sales.

Other expert witnesses argued for somewhat higher gross margins under the theory that intercompany contracts represented a standard distributor model.

The primary argument from the taxpayer’s experts, however, was that the Swiss affiliate was the entrepreneurial risk-taker taking on the downside risk during the 1999 to 2002 period and entitled to upside potential during periods when uranium prices were higher than expected.

The volatility of uranium prices was emphasized by the expert witnesses for Cameco during the trial. The Canada Revenue Agency noted the implications of the commodity boom that started in 2003.

Off-take arrangements

These experts, however, offered very little in terms of how the intercompany contract compared to third party contracts in the uranium sector.

These experts, however, offered very little in terms of how the intercompany contract compared to third party contracts in the uranium sector.

The claim that the intercompany transaction must be structured as a limited risk distributor arrangement is faulty as third-party off-take agreements exist in the uranium sector, as I pointed out in my 2014 publication on the gross margins for mining marketing affiliates: (“Evaluating Whether a Distribution Affiliate Pays Arm’ s-length Prices for Mining Products,” Journal of International Taxation, July 2014).

The ability to extract natural resources requires significant upfront commitments of capital. If the owner of natural resources is uncertain as to whether the future economic rents will cover these upfront commitments and provide a reasonable return, he will be reluctant to incur the upfront costs.

Off-take agreements guarantee the owner of natural resources that his future revenues will provide a reasonable return on investment. The buying entity in an off-take agreement agrees to pay a certain future price to the producing entity for its production. The distributor becomes the entrepreneur. Since the distributor takes the downside risk that spot prices will be below the agreed-on future price, it also should receive the upside potential.

Off-take agreements in the uranium sector often cover periods from five to seven years. A recent example is the agreement by Curzon Uranium Trading Limited to purchase 800 thousand pounds of U₃O₈ from Aura Energy’s Tirus Uranium Project at a fixed price of CAN44 per pound. The agreement was concluded on January 29, 2019, and continues through the end of 2025.

The fixed price was significantly above the mine’s cost of production, so this agreement provides Aura Energy with significant economic rents. Uranium prices in early 2019 were less than CAN29 per pound, so the contract suggests that the two parties expected a significant rise in uranium prices over the life of the contract.

Risk shifting

It could be argued that Cameco’s arrangement with its Swiss affiliate operated in the same way as an off-take arrangement by shifting risk the risk of uranium pricing changes to the marketing entity and away from the producer.

Veritas Investment Research discussed uranium pricing volatility and Cameco’s transfer pricing issue in an April 2, 2013, report. The report said that Cameco’s long-term contract with its Swiss marketing affiliate exposed the Swiss affiliate to the downside risk when uranium prices were low as well as the upside potential if uranium prices rose.

The Veritas report also said, however, that the Cameco 1999 Annual Report suggested that there was significant potential for higher uranium prices over the next ten years. Under arm’ s-length pricing, such expectations would imply that the producer would expect economic rents, which should have been reflected in any long-term negotiations.

The Veritas report also said, however, that the Cameco 1999 Annual Report suggested that there was significant potential for higher uranium prices over the next ten years. Under arm’ s-length pricing, such expectations would imply that the producer would expect economic rents, which should have been reflected in any long-term negotiations.

Anticipated uranium prices

The Cameco court focused on disagreements between the expert witnesses for both sides on how much downside risk that the Swiss affiliate faced but spent little time discussing the expectations of uranium prices in 1999 for the period of the intercompany contract were.

The one possible exception was the valuation method provided by Dr. Barbera:

Under the [valuation method], Doctor Barbera computes a fixed price for the terms of [certain long-term contracts (BPCs)] based on the discounted present value of the profit expected to be earned over the terms of the BPCs. The expected profit is in turn based on the Appellant’s forecast of future realized price around the times the BPCs were entered into. To determine this profit, the expected revenues are discounted by 10% to reflect the risk of the hypothetical arrangement and are also reduced by the costs of [the Swiss subsidiary] and Cameco US and by a routine profit (based on certain arm’s length indicators) for their functions and capital investments. These costs and routine profit collectively required a further discount of 3.5%. The result is a fixed price of $14.96 for the two BPCs dated October 25, 1999 and May 3, 2000 and $12.43 for the balance of the BPCs. These prices are then increased each year by the rate of inflation. The revenues computed using these prices are then compared to the actual revenues from the BPCs to determine the adjustment. The total adjustment for the Taxation Years is an increase in the income of the Appellant of CAN $241.3 million.

A footnote to this passage from the court decision noted:

The forecasts are taken from a September 1999 strategic plan and slides prepared by the Appellant in November 2000. The slides had forecasted spot prices which Doctor Barbera discounted by 5% to generate a proxy for forecast realized prices.

The Veritas Investment Research report noted that Cameco told shareholders in 1999 that it anticipated uranium prices to rise.

Contract length

The idea that this intercompany contract was extended for such a long period of time begs the question as to what was the market’s expectation of uranium prices over the life of the intercompany contract.

The idea that this intercompany contract was extended for such a long period of time begs the question as to what was the market’s expectation of uranium prices over the life of the intercompany contract.

Without addressing this key issue, evaluating how much expected economic rent was transferred would not be possible.

It is interesting to note that uranium prices averaged USD47.27 per pound over the 2009 to 2013 period but averaged only USD28.68 per pound over the 2014 to 2018 period.

It is also interesting to note that uranium prices averaged USD11 per pound over the 1999 to 2004 period.

Had the intercompany contract been a six-year fixed price agreement at USD10 per pound, the Swiss affiliate’s early losses would have been fully recouped in 2003 and 2004 when uranium prices exceeded the intercompany contract.

It seems that the economics of Cameco’s agreements do not necessarily support the USD10 per pound intercompany price, at least for years after 2004.

Be the first to comment