By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

The latest edition of the United Nations Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries, released April 27, includes some useful observations on the nature of intangible assets, their creation, and the key issue of ownership among multinational group affiliates.

The chapter, however, has a very sparse discussion of the evaluation of intercompany royalty rates. As affiliates in developing nations are often licensees and not owners of valuable intangible assets, a more thorough discussion of what constitutes an arm’s length royalty rate would be welcome.

Valuing transferred intangibles

Section 6.3.3 is entitled the significance of DAEMPE, where DAEMPE stands for development, acquisition, enhancement, maintenance, protection, and exploitation of intangible assets. Other discussions have coined the term DEMPE by leaving out the important aspect of where one affiliate acquires intangible assets originally developed by another affiliate.

The UN manual provides several examples of the valuation of acquired intangible assets, including an example of the probability-weighted discount cash flow model.

Consider the UN manual’s example of a pharmaceutical multinational with a Swiss parent, a Hungarian affiliate that does both early-stage R&D and contract manufacturing, and distribution affiliates in Western Europe.

The Hungarian affiliate developed viral treatments through phase II trials which were concluded at the end of 2018. This in-process R&D was sold to the Swiss parent, with the Swiss parent conducting phase III trials in 2019 and 2020. The hope was to license the product intangibles starting in 2021, where the Hungarian affiliate would act as a contract manufacturer, and the Western European affiliates would act as distributors on behalf of the Swiss owner of the fully developed production intangibles.

R&D expenses were $100 million per year both in 2019 and in 2020. There were three sets of sales projections. There was a 25 percent chance that no sales would be made as the probability of obtaining regulatory approval was only 75 percent. There was a 25 percent chance that this new treatment would be a blockbuster, generating $750 million per year. The most likely scenario with a probability of 50 percent was that sales would be $250 million per year. The probability-weighted scenario had expected sales equal to $312.5 million per year.

Production costs were estimated to be equal to 40 percent of sales, and selling expenses were estimated to be equal to 20 percent of sales. As such, projected operating profits from 2021 through the life of the product intangibles represent 40 percent of sales or $125 million per year. The UN example assumed that the product’s intangible life extends only to 2023. A more likely scenario would be to consider that the product’s intangible life extends to 2028.

The UN example assumes that the combined routine returns for production and distribution is only $10 million per year, which it notes represents a 5.33 percent markup over the sum of production costs and selling expenses.

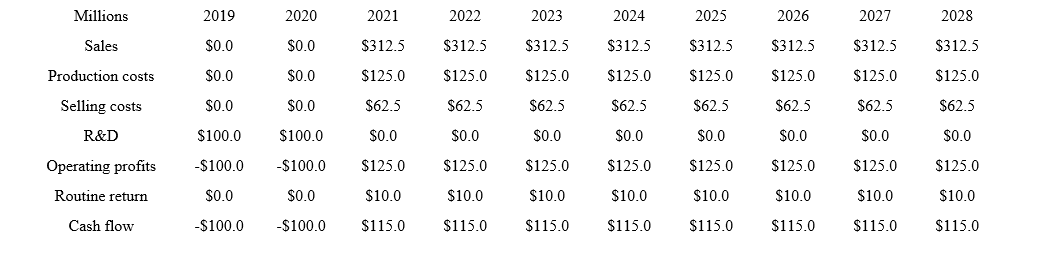

Table 1 shows projected income and cash flows (CF) under these assumptions, where cash flows represent operating profits minus routine returns. Cash flows are negative $100 million per year for 2019 and 2020 and are $115 million per year from 2021 onwards. The routine returns in the UN example represent only 3.2 percent of sales (S), with cash flows representing 36.8 percent of sales.

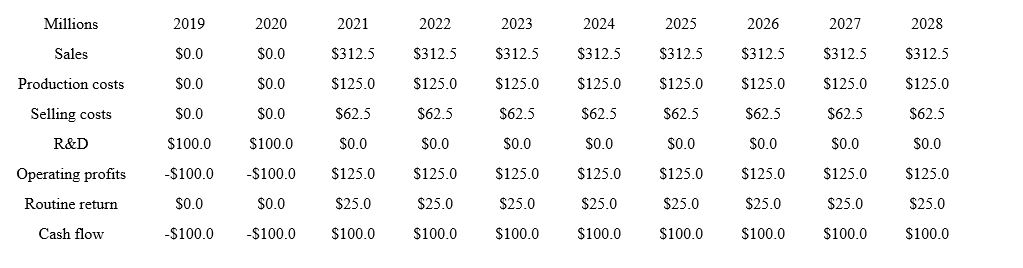

Table 2 presents an alternative model where routine returns represent 8 percent of sales, so cash flows are 32 percent of sales. If the routine return to production represents a 10 percent markup, then this routine return alone is $12.5 million per year or 4 percent of sales.

If the routine return for distribution represents a 20 percent markup over its selling costs, then this routine return alone represents another $12.5 million or 4 percent per year.

The tax authorities in Hungary and Western Europe would likely argue for higher routine returns than those assumed in Table 1.

Table 1: Projected Profits and Cash Flows Assuming Modest Routine Returns

Table 2: Projected Profits and Cash Flows Assuming Higher Routine Returns

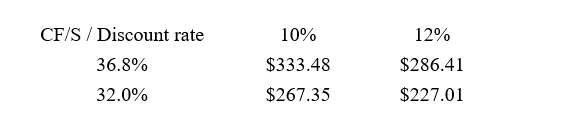

The fair market value for the transferred intangible depend not only on the assumed projected income but also on the estimate of the routine returns, the economic useful life of the product intangibles, and the appropriate discount rate.

The UN example assumed the lower estimate of routine returns, as well as a rather short economic useful life, as the projections were extended only through 2023. If the discount rate were 12 percent, the estimated value would be only $51.2 million. If the discount rate were 10 percent, the estimated value would be only $62.8 million.

If the economic useful life extends through 2028, the estimated value would be $333.48 million if the discount rate were 10 percent. If the discount rate were 12 percent, the estimated value would be $286.41 million.

The issue of the economic useful life is a crucial and often contentious issue between multinationals and tax authorities.

We also noted that the UN example assumes a low estimate of the routine returns for the Hungarian contract manufacturer and the distribution affiliates.

Table 2 assumes that the combined routine returns for manufacturing and distribution represent 8 percent of sales, so cash flows are only 32 percent of sales. If the economic useful life extends to 2028 and the discount rate is 10 percent, the value estimate is $267.35 million. If the discount rate is 12 percent, the value estimate is $227.01 million.

Table 3 summarizes how the value estimate depends on the ratio of cash flows-to-sales and on the discount rate.

Table 3: Fair Market Value Under Alternative Assumptions

Longer assumed economic useful lives and lower discount rates tend to increase the estimated fair market value for transferred intangible assets. The probability-weighted discounted cash flow model also stresses the prospect that the phase III trials will not succeed in developing a commercially viable treatment.

The UN example put this probability at only 25 percent, which may seem low given the frequency of failure for previous pharmaceutical R&D projects. However, the remarkable success at developing vaccines for COVID-19 suggests that pharmaceutical multinationals are more adept at creating new breakthroughs.

Licensing structures

Our discussion of the estimation of the fair market value of the transferred intangible assets assumed a structure where the Swiss parent exploited the intangible assets that it had acquired by separately contracting with the Hungarian contract manufacturer and with the Western European distribution affiliates.

In many cases, however, the Swiss owner of the intangible assets licenses its product intangibles to the operating affiliates as licensees paying intercompany royalties.

The UN manual provides little guidance on the appropriate royalty rate. While it does note the use of the comparable uncontrolled price approach, this approach is often not viable if the product intangibles are unique and very valuable.

The guidance also appears to endorse the use of the transactional net margin method (TNMM). If we use the assumptions in Table 2, where consolidated profits represent 40 percent of sales, the routine return to production is 4 percent of sales, and the routine return for distribution is 4 percent of sales, then residual profits would be 32 percent of sales. A TNMM approach would therefore suggest a royalty rate equal to 32 percent of sales.

Tax authorities in developing nations are likely facing transfer pricing reports from multinationals that justify very high royalty rates based on such applications of TNMM. These tax authorities may wish to challenge the implicit premise that the formal owner of the intangible assets deserves 100 percent of residual profits. The UN manual also makes this brief statement:

A profit split method may be the most appropriate method if each party to a transaction makes unique and valuable contributions, the parties are highly integrated, or they share significant risks.

The IRS is contending that the licensor should get all the residual profits in recent high-profile disputes over intercompany royalty rates where consolidated profits are 40 percent of sales or more.

The multinational’s position in these litigations is that the licensee deserved a considerable portion of residual profits because it allegedly owns a portion of the valuable intangible assets. The role of upfront marketing is often an important consideration in the pharmaceutical sector.

Even if the licensor owns not only the product intangibles but also the marketing intangibles, third-party licensees still bear considerable entrepreneurial risk when exploiting valuable intangible assets owned by another entity.

This brief statement in the UN manual on the appropriateness of the profit split method warrants more consideration.

Be the first to comment