By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

The UN, on April 27, released a new edition of the United Nations Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries, including its latest chapter on transfer pricing for the extractive industries.

The release of the updated manual followed a UN Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters virtual meeting, held April 21. At that meeting, the Committee noted ongoing controversies in the extractive sector regarding the intercompany interest deduction, specifically, how to determine if intercompany financing represents debt versus equity and what would represent an arm’s length interest rate.

The examples presented in the United Nations practical manual’s chapter on intercompany financing illustrate the issues surrounding the appropriate credit rating and the terms in an intercompany contract in a straightforward way.

The extractive sector would benefit from following this guidance and applying a similar focused and principled approach when evaluating intercompany interest rates.

Arm’s length intercompany interest rates

A standard model for evaluating whether an intercompany interest rate is arm’s-length can be seen to have two components — the intercompany contract and the credit rating of the related party borrower. Properly articulated intercompany contracts stipulate:

- The date of the loan;

- The currency of denomination;

- The term of the loan; and

- The interest rate.

The first three items allow the analyst to determine the market interest rate of the corresponding government bond. This intercompany interest rate minus the market interest rate of the corresponding government bond (GB) can be seen as the credit spread implied by the intercompany loan contract.

UN practical manual examples

Chapter 9 of United Nations Practical Manual on Transfer Pricing for Developing Countries includes sixteen examples illustrating the determination of intercompany interest rates and loan guarantees.

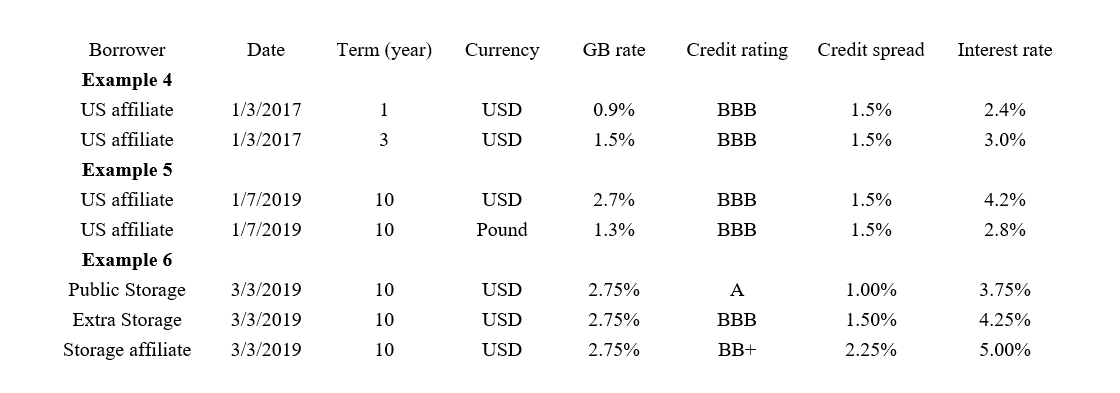

The following table provides information to illustrate examples 4, 5, and 6. Example 4 focuses on the term of the loan, and Example 5 focuses on the currency of denomination, and Example 6 addresses the role of the estimated credit rating of the borrowing affiliate. For both Example 4 and 5, assume a US affiliate with a BBB credit rating.

Example 4 provides that the loan agreement was made in January 2017 at a fixed interest rate of X% with a twelve-month term. The principal was repayable at the end of the term. The example specifies that BCo has continued to pay interest at X% on the loan in its 2018 and 2019 financial periods. BCo and LCo exchanged letters in January 2018 to confirm the extension of the loan for a further period of twelve months and repeated the exchange in January 2019.

Consider a German parent extending an intercompany loan to its US affiliate on January 3, 2017. At the time, the one-year US government bond rate was only 0.9 percent, while the three-year US government bond rate was 1.5 percent. Assume that the original intercompany loan was 2.4 percent, which would be consistent with the BBB credit rating and 1.5 percent credit spread.

As the example noted, however, this 2.4 percent interest rate was used for an extension of the loan through 2018 and again through 2019 even though interest rates in the US rose during this period.

The German tax authorities could recast the intercompany loan as a three-year fixed interest rate loan. Under this recharacterization, the arm’s length interest rate would be 3 percent.

An alternative interpretation would be to see this arrangement as akin to a floating rate loan with the one-year government bond rate on the first business day of each year as the base and the 1.5 percent credit spread as the loan margin.

While the 2.4 percent interest rate would be arm’s length for 2017, the arm’s length interest rate for 2018 would be 3.33 percent since one-year government bond rates had risen to 1.83 percent. For 2019, the arm’s length interest rate would be 4.1 percent under the floating rate interpretation since one-year government bond rates had risen to 2.6 percent.

Loan currency

In Example 5, Borrowing Company, BCo, pays loan interest to Lending Company, LCo. BCo and LCo are associated enterprises. The loan agreement specifies that the advance is denominated in currency X. On further examination, it is found that the advance was made in currency Y, and regular interest payments have been made in currency Y computed on the outstanding balance expressed in currency Y.

To illustrate this example, consider a ten-year fixed interest rate intercompany loan from a UK parent to its US affiliate on January 7, 2019. The interest rate on ten-year US government bonds was 2.7 percent. If the appropriate credit spread were BBB, so the credit spread is 1.5 percent, then the arm’s length interest rate would be 4.2 percent.

Example 5, however, suggests that the appropriate currency of denomination should be the UK pound. The interest rate on ten-year UK government bonds was 1.3 percent. If the appropriate currency of denomination were the UK pound, then the arm’s length interest rate would be 2.8 percent.

Credit rating

Example 6 describes a loan agreement where $5 million was advanced by LCo to associated enterprise BCo on March 3, 2019, at a fixed interest rate of 5% and for a ten-year term. BCo, part of the MNE, XtraStore, rents storage to customers and owns storage premises. On March 3, 2019, BCo completed the purchase of two premises for $6 million. At the same time, BCo repaid the outstanding principal of $1 million on a loan from a third-party bank.

After repayment of the bank loan, BCo does not have any remaining third-party borrowings, and none of its assets are pledged in security. LCo has several bank loans, all of which (apart from short-term facilities) are secured on its storage premises. Similarly, most other term loans of the MNE from banks are secured on the storage premises assets of the borrower entity. The previous bank loan that BCo repaid in March 2019 was secured on its assets held before that date.

The interest rate on ten-year US government bonds was 2.75 percent. The 5 percent intercompany interest rate paid by the storage subsidiary implies a 2.25 percent credit spread for the borrowing affiliate. This credit spread is consistent with a credit rating of BB+.

Example 6 appears to be based on assigning the multinational’s group credit rating as the appropriate credit rating for this analysis. Consider two publicly traded US storage companies, Public Storage’s credit rating is A, which implies a credit spread of only 1 percent. Extra Storage’s credit rating is BBB, which implies a credit spread equal to 1.5 percent.

If the tax authority for the borrowing subsidiary asserts a credit spread between 1 percent and 1.5 percent, the arm’s length interest rate would be between 3.75 percent and 4.25 percent.

Loan pricing

Example 9 from the Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters is entitled “Transfer Pricing Issues of Loan Pricing.” The example posed a five-year fixed interest rate intercompany loan with an interest rate equal to 12.5 percent. The date of the intercompany loan was January 30, 2018, and the currency of denomination was the Euro. The interest rate on five-year German government bonds at the time of this intercompany loan was approximately 0.5 percent, so the intercompany loan had an implied credit spread equal to 12 percent.

The example stated that the borrowing affiliate’s credit rating was BBB. Credit ratings are letter grades, which require translating into a numerical credit spread. The example claimed that the representatives of the taxpayer argued for a 9 percent credit spread.

Credit spreads for BBB-rated corporate bonds were only 1.5 percent in early 2018. Even during the period after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in late 2008, credit spreads peaked at only 5 percent for BBB-rated corporate bonds.

The fallout from the COVID-19 crisis saw a temporary spike in credit spreads, but the peak spread for BBB rate corporate bonds was only 4 percent. If the credit spread on the intercompany loan was BBB, any claim that the credit spread should be 9 percent has no merit.

Even if one could argue for a 9 percent credit spread, this assertion would justify a 9.5 percent interest rate, not the 12.5 percent intercompany interest rate. The example also stated that the representatives of the taxpayer had a transfer pricing study for another intercompany loan where the interest rate was 3.5 percent. This intercompany loan was denominated in US dollars, not Euros, and involved a 10-year fixed interest rate issued sometime in 2017.

Interest rates on ten-year US government bonds averaged 2.3 percent during 2017 but were 2.5 percent as of January 8, 2018, and continued to rise to 2.75 percent by January 30, 2018. The precise date of this other intercompany loan is an important fact to know.

Assume that the loan was issued on October 17, 2017, when the interest rate was 2.3 percent. A 3.5 percent interest rate is consistent with the A- credit rating of this particular borrowing affiliate, which would imply a 1.2 percent credit spread.

The example also stated that the parent corporation had a credit rating of A+, which implies a group credit spread of 0.7 percent and a 3 percent interest rate. If the parent granted an explicit loan guarantee to this other borrowing affiliate, then it could charge a guarantee fee under the arm’s length standard and not the example’s 1 percent fee.

If the taxpayer were using the 3.5 percent intercompany interest rate as some sort of base rate for the 12.5 percent intercompany interest rate, this characterization injects all sorts of confusion, if not misrepresentations. Interest rates on ten-year US government bonds are not the same as interest rates on five-year Euro-denominated bonds.

Interest rates also vary over time as well as with respect to the credit rating of the borrowing affiliate. As such, the information in the other intercompany pricing study would have little to offer for the Euro-denominated intercompany loan, even if that information was reasonable.

While an appropriate analysis of the intercompany interest rate in this example simply combines the 0.5 percent interest rate on the corresponding government bond rate and the 1.5 percent credit spread given the BBB credit rating, it appears that the taxpayer’s representatives present a confusing evaluation, hoping to defend a clearly excessive intercompany interest rate.

These types of controversies are also occurring between European taxpayers and the French tax authority. In a recent Edgarstat blog entitled “Challenges to Intercompany Loan Rates by French Tax Authority and IRS,” I discuss this European controversy.

Be the first to comment