By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

The Korean affiliates of hi-tech multinationals such as Facebook, Google, and Netflix have recently provided 2020 financial statements to Korea’s Financial Supervisory Service according to recent news accounts in Pulse and KoreaJoonAng Daily. Netflix recorded 415.5 billion won, which translates into approximately USD 352 million at the average exchange rate for 2020. Netflix’s operating profits were approximately 2.1 percent of sales.

The South Korean tax authorities have also been questioning the transfer pricing practices of these multinationals as I discussed in my September 1, 2020, MNE Tax article with respect to Netflix. This new financial reporting offers a chance to revisit the possible issues for Netflix’s transfer pricing issues in South Korea.

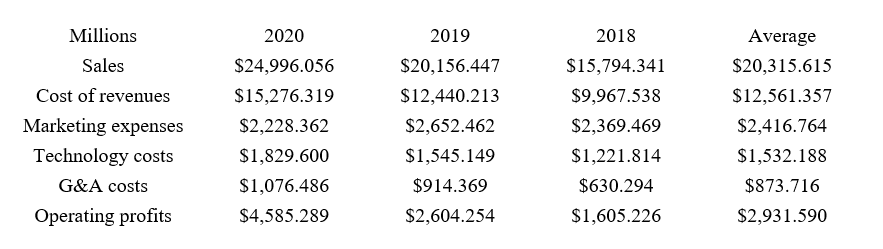

Table 1 presents Netflix’s consolidated income statement for the last three fiscal years. In 2020, worldwide sales were almost $25 billion with approximately 9.5 percent of those sales from the AsiaPac region. The reported sales in South Korea were 1.4 percent of worldwide sales.

Table 1: Netflix Income Statement – 2018 to 2020

Netflix’s operating margin rose from 10.16 percent in 2018 to 18.34 percent averaging more than 14.4 percent during this period. If consolidated profits from South Korean sales represented 14 percent of sales, the 2.1 percent operating margin retained by the South Korean affiliate would be only 15 percent of these consolidated profits.

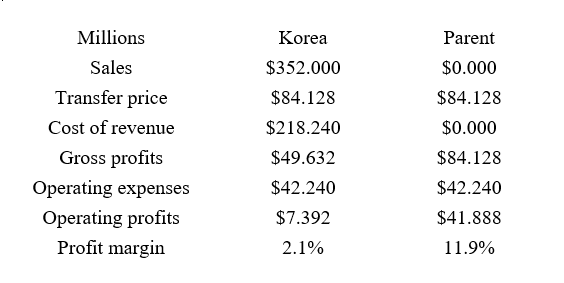

Table 2 illustrates the transfer pricing issues using a hypothetical set of income statements that assumes:

- South Korean sales = $352 million;

- Cost of revenues borne by the local affiliate = 62 percent of sales;

- Marketing expenses borne by the local affiliate = 12 percent of sales;

- Technology costs borne by the parent = 7.5 percent of sales; and

- General and administrative (G&A) costs borne by the parent = 4.5 percent of sales.

Consolidated operating profits = 14 percent of sales, which is allocated between the South Korean affiliate and the parent according to the transfer pricing policy. Table 2 assumes that the South Korean affiliate pays the parent intercompany fees for management and the value of licensed intangible assets = 23.9 percent of sales. Under this transfer pricing policy, the South Korean affiliate’s gross profits (sales minus cost of revenue minus intercompany fees) represent 14.1 percent of sales and its operating profits (gross profits minus marketing expenses) represent 2.1 percent of sales. The parent retains profits that represent 11.9 percent of sales from the South Korean operations.

Table 2: Illustration of Netflix Korea’s Transfer Pricing

The 2.1 percent operating margin for the South Korean affiliate represents a 17.5 percent markup over its operating expenses. Transfer pricing practitioners often defend such positions using an application of the transactional net margin method (TNMM), which make a host of assumptions that require scrutiny. One assumption is that the parent owns all of the valuable intangible assets. A reliable defense of a 17.5 percent markup would also require that the distribution affiliate has a very modest tangible asset to sales ratio.

Netflix notes that it obtains content through its own production of original programming, acquisition of content, and licensing. For content that is either produced or acquired, Netflix records on its balance sheet the capitalized cost of the content. For license content, the balance sheet records both an asset value for the fee per title as well as a liability for the license fees that it will incur. Content assets net of content liabilities is approximately 80 percent of revenue.

If the parent owns these content assets, then a TNMM analysis that focuses only on the working capital of the South Korean distribution affiliate would be reasonable. If the distribution affiliate, however, takes title to these content assets, then the appropriate operating margin must consider the profits to these content assets. Given that the assets net of liabilities represents 80 percent of sales, the additional compensation could be considerable.

My September 1, 2020, discussion of Netflix South Korea’s transfer pricing noted that this affiliate incurred operating losses during its initial years of operations. While the Korean tax authorities argued that operating losses were evidence that the intercompany fees from the parent were excessive, I noted the possibility that the losses were due instead from temporarily high marketing expenses relative to sales under a market share approach.

Market share strategies under arm’s length pricing often witness periods where the upfront market expenses are very high relative to early sales such that overall operating expenses exceed gross profits. As sales grow, the operating expense to sales ratio declines below the gross profit margin. Hence, the local affiliate enjoys sufficient long-run profits to compensate it for both its routine return and a reasonable return on its initial investment by incurring the upfront marketing.

This market share defense of early operating losses, however, would not be consistent with the use of TNMM to defend modest operating margins under the premise that the distribution affiliate deserves only routine returns to current marketing expenses. A consistent approach would require some mechanism for the South Korean affiliate to be compensated for its upfront marketing expenses.

Be the first to comment