By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

The European Commission launched an initiative on May 20 to address the use of shell companies in international arrangements to reduce income taxes. The initiative hopes to define substance requirements for arrangements operating in the European Union.

The question becomes, what is a shell company and how do they reduce income taxes?

The initiative defines shell companies as “legal entities with no or only minimal substance, performing no or very little economic activity continue to pose a risk of being used in aggressive tax planning structures.”

Edward Kleinbard coined the term “stateless income” as the use of intercompany interest, rent, and royalty charges to shift income to tax havens. While the use of such intercompany charges is commonplace, are the recipients of such intercompany income shell companies, or are they affiliates with substance, as defined by the OECD and the Court of Justice of the European Union?

Intercompany Financing

The only litigation noted by the initiative is the September 12, 2006 judgment by the Court of Justice of the European Union in Cadbury Schweppes plc and Cadbury Schweppes Overseas Ltd v Commissioners of Inland Revenue.

Cadbury Schweppes plc was a UK-based multinational producing and selling chocolates and carbonated beverages. Cadbury established a financing affiliate in Ireland that earned approximately £9 million in income during 1996.

While the UK tax rate was 30 percent, the Irish tax rate was only 10 percent. The UK government established tax rules that would allow the UK tax authorities to include this Irish income in the UK tax base.

The EU Court of Justice ruled against the UK government even though it did recognize the concept of “wholly artificial arrangements” to be considered in the context of anti-abusive tax measures. This Irish affiliate, however, was seen as having substance.

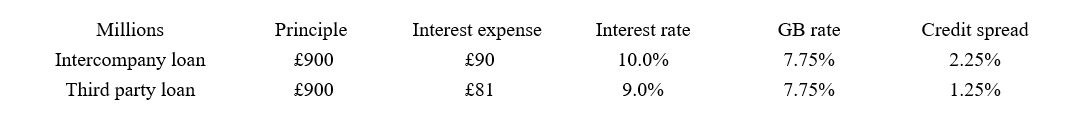

While the Court’s decision did not discuss how the Irish affiliate generated its income, Table 1 lays out an illustration of the typical intercompany financing arrangement.

Financing affiliates incur third-party debt for the multinational and then extend intercompany loans to the operating affiliates. In 1996, the exchange rate was such that one British pound was worth approximately $1.67 and the interest rate in 10-year UK government bonds (GB) was 7.75 percent.

Table 1 assumes that the financing affiliate borrowed £900 million at an interest rate equal to 9 percent and extended intercompany loans to its operating affiliates at an interest rate equal to 10 percent.

The financing affiliate’s intercompany revenue would be £90 million while its expenses would be £81 million, thus generating £9 million in profits.

Table 1: Illustration of Cadbury Schweppes Intercompany Financing

Tax authorities could have challenged the 10 percent intercompany interest rate even if the claim of being an abusive tax arrangement was not upheld.

Table 1 shows the credit spread, defined as the interest rate minus the interest rate on the corresponding government bond rate, for both the third-party loan and the intercompany loan.

The 1.25 percent credit rate on the third-party loan is consistent with a group credit rating of BBB+. The 2.25 percent credit rating on the intercompany loan assumes a credit rating of BB+ for the borrowing affiliate. Tax authorities have recently challenged intercompany interest rates based on assumed credit ratings below the group rating.

Centralized leasing

Oil drilling rig multinationals achieve low effective tax rates through a planning technique that is alternatively referred to as bareboat chartering or centralized leasing.

Oil drilling rig multinationals are very capital-intensive enterprises, with over 80 percent of the capital being in the form of expensive drilling rigs. These rigs are formally owned by tax haven affiliates, which tend to charge very high intercompany lease rates. Even under arm’s length lease rates, this planning often sources about half of the worldwide profits in the tax haven affiliate.

In 2014 the UK government accused these multinationals of paying overly generous intercompany rents to their leasing affiliates. The Bareboat Charter Act sought to legislatively cut their lease rates in half.

At the time, Transocean received approximately $8 billion in third-party revenue and enjoyed operating profits near 30 percent of sales. Half of these revenues were booked by its US, UK, and Norway affiliates, with about $2 billion being booked by the US affiliates. Its North Sea affiliates in Norway and the UK collectively booked the other $2 billion.

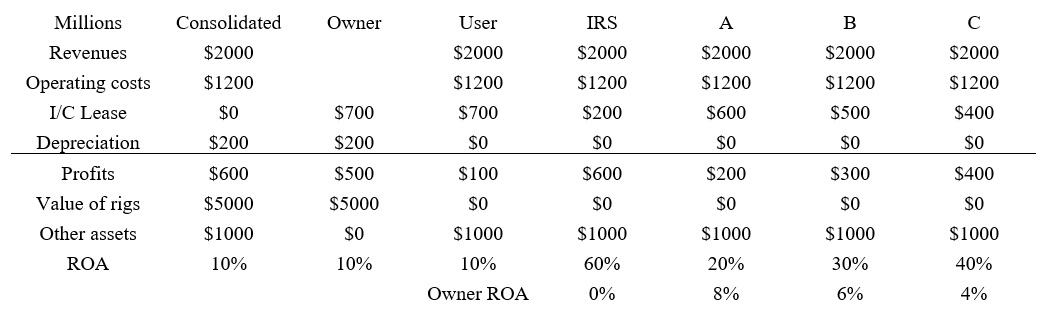

Table 2 presents the consolidated financials for the US affiliate assuming:

- Operating costs = 60 percent of revenues;

- Depreciation = 10 percent of revenues; and

- Total operating assets represent 3 times revenues.

The $6 billion in total operating assets consists of $5 billion in rigs owned by the tax haven affiliate and $1 billion in other assets owned by the operating affiliate. Consolidated operating profits represented 10 percent of total operating assets. This return on assets (ROA) was consistent with Transocean’s cost of capital.

Table 2: An Illustration of Transocean’s Intercompany Leasing Charges

Table 2 considers various transfer pricing policies with respect to the intercompany (I/C) lease payment.

The actual intercompany policy can be seen as a 14 percent lease (L) to the value of rigs (V). The L/V ratio captures the sum of the depreciation rate plus the rig owner’s cost of capital. The depreciation rate in our example is 4 percent so the intercompany policy affords both the leasing affiliate and the operating affiliate with a 10 percent ROA on the assets they formally own.

Paragraph 63 of the BEPS discussion draft on Action 9 captures an important consideration from the financial economics of leasing:

Risks should be analyzed with specificity, and it is not the case that risks and opportunities associated with the exploitation of an asset, for example, derive from asset ownership alone. Ownership brings specific investment risk that the value of the asset can increase or may be impaired, and there exists risk that the asset could be damaged, destroyed or lost (and such consequences can be insured against). However, the risk associated with the commercial opportunities potentially generated through the asset is not exploited by mere ownership.

The 10 percent cost of capital for the oil drilling sector can be thought of as the sum of a 4 percent risk-free rate plus a 6 percent premium for bearing systematic risk. This systematic risk can be decomposed into a premium for bearing ownership risk and a premium for bearing commercial risk. The leasing affiliate only bears ownership risk, which implies it does not deserve a 10 percent expected return to assets as it does not bear commercial risk.

The IRS position in its original challenge to the transfer pricing for Transocean was based on the implicit premise that the intercompany lease charge should cover only depreciation thereby leaving the leasing affiliate with no profits. This position was ultimately abandoned as being consistent with financial economics.

The UK bareboat charter law is based on the premise that the leasing affiliate deserves only the risk-free rate.

Column C of Table 3 shows the implications of this extreme position that ignores the role of ownership risk borne by the formal owner of the rigs.

Columns B and C capture the implications of a model where the formal owner is rewarded with the return for bearing ownership risk and the operating affiliate is rewarded with the return for bearing commercial risk on the use of leased drilling rigs. If the premium for bearing ownership risk is 2 percent, then the formal owner deserves a 6 percent ROA, which sets L/V = 10 percent. Under this transfer pricing policy (column B), the lease payment would be $500 million, which splits consolidated profits evenly.

Some tax authorities have unsuccessfully argued that the profits from the leasing affiliate be included in the tax base of the operating affiliate. The Norwegian tax authority attempted to use permanent establishment to accomplish this result, but the courts rejected this argument in favor of evaluating whether the lease payment is arm’s length.

The IRS assertion in its original challenge to Transocean would have had a similar effect, but this assertion was rejected as not being a proper application of the arm’s length standard.

While centralized leasing has withstood these challenges, tax authorities can still challenge whether the actual intercompany lease charges exceed arm’s length rates.

Intangible holding affiliates

Action 13 of the BEPS initiative has armed tax authorities with country-by-country reporting. Representatives of multinationals have raised concerns that tax authorities will misuse the information on head counts and tangible assets to allocate income across jurisdictions.

The concern is that country-by-country reporting does not account for the value of intangible assets. A recent audit by the Austrian tax authorities has been used as an illustration of this alleged abuse.

An Austrian affiliate of a Swiss-based multinational performed both research and development (R&D) functions as well as manufacturing functions. The policy of this multinational was to compensate the Austrian affiliate on a cost-plus basis for the manufacturing functions and for the R&D functions.

The implicit assumption by the multinational was that the Austria entity performed contract R&D and contract manufacturing functions. Any profits attributable to the multinational’s intangible assets resided with the Swiss parent. The Austrian tax authority argued that the Austrian affiliate had created valuable intangible assets, which would have required a profit split approach that split profits based on head count.

While the Austrian tax authority is likely asserting that the product and process intangible assets were created by the Austrian affiliate and not the Swiss parent, the issue of which legal entity owns the marketing intangibles should also be explored.

If the goods manufactured in Austria are sold to French and German customers, the gross margins for the Western European distribution affiliates is another transfer pricing issue. Multinationals often based these gross margins on distribution costs and routine returns for distribution. The French and German tax authorities, however, might assert that the marketing intangibles were created by the distribution affiliates.

A defense of the multinational’s transfer pricing policies would require that it could be demonstrated that the Swiss affiliate had both substance and created the intangible assets. If the Swiss affiliate, however, had few employees and had never incurred intangible development costs, then it could be seen as a shell company.

The state aid case involving Amazon Luxembourg is an illustration of this potential controversy. In my May 24 discussion entitled “The EU Commission’s objections to Amazon’s transfer pricing approach,” I noted the European Commission wanted to base the income of the intangible holding company as being a modest markup on the costs incurred to maintain its legal ownership of the intangible assets.

The implicit assumption that the Luxembourg intangible holding company did not own the European rights to Amazon’s intangible assets was rejected by the General Court of the European Union.

A May 7 Russian Arbitration Court ruling on intercompany royalties illustrates how tax authorities may challenge arrangements that they deem lack substance.

Johnson Matthey PLC is a UK-based multinational designing and producing products such as emission controls products made from various chemicals and precious metals. A Dutch affiliate charged a Russian operating affiliate intercompany royalties equal to 6 percent of sales for the alleged use of certain know how.

The Russian tax authority noted that the Russian affiliate used this know how before the intercompany licensing agreement was initiated. Decision A33-5437/2020 agreed with the tax authority that these intercompany royalties should be denied on the grounds that the Russian affiliate was aware of this know-how before any intercompany agreements was in place.

This ruling will be certainly controversial, and its raises questions as to what the underlying reasoning was. Did the Court believe that the intangible asset had no economic value, or did it believe that the Russian affiliate and not the licensing affiliate-owned this know-how?

Any denial of tax benefits from an alleged shell affiliate raises similar issues. Whether this affiliate is entitled to intercompany royalty income depends on what, if any, intangible assets it owns.

Even if the affiliate is deemed to own certain intangible assets, the transfer pricing question remains how much are these intangible assets worth in terms of an arm’s length royalty rate.

Need to note that in Decision A33-5437/2020 not the Dutch affiliate but UK based JM PLC (the owner of developed know how) charged a Russian operating affiliate intercompany royalties for the alleged use of certain know how. And it is also very important to note that the Russian court considered several questions, e.g. the deductibility of royalties for the use of know how received before signing of license agreement; the economic value of know how (here the judgement was made basing on the expert’s report (in my personal opinion the expert was unqualified, as he has an experience in assessment of value of intellectual property and value of immobilities, and his main education is an woodworking, though in the report of expertise he described the chemistry and technology of catalysis)); the re-qualification of royalties in dividends and applicable tax rate on DTT between Russia and UK.

This dispute was highly discussed within community of Russian tax experts, and is remarkable tax case forming the recent negative practice against taxpayers in Russia in cases where the evidence for taxpayer’s favour is ignored though the evidence for tax authorities’ favour is accepted by court without any doubt.

Interesting comments regarding the expert witnesses and their evaluation of the economic value of the know how. Are these reports available to review as I noted to some others privately that a 6% royalty rate was implausibly high. But the other real way to know would be to review the competing economic analyzes.