By Susi Baerentzen, Ph.D., Copenhagen

The General Court of the European Union on September 23 ruled in the Spanish tax leasing case, aka the Lico Leasing case, that had been referred back from the European Court of Justice in 2018.

The case has led a turbulent life bouncing back and forth between the European Commission, the General Court of the European Union, and the European Court of Justice.

It serves as a good example of an overall tendency in state aid cases on taxation; with the Commission, on one hand, having a very clear agenda to push their policies and on the other hand with the EU courts in search of principle.

The maze of the Spanish tax leasing scheme

The scheme in question applied to finance agreements for the purchase of ships and made it possible for shipping companies to purchase ships built by Spanish shipyards at a 20-30% discount.

The system in itself was quite the bundle of arrangements, as each ship contract involved a shipping company, a shipyard, a bank, a leasing company and an economic interest grouping made up of investors who owned its shares.

The grouping took a lease on the ship from a leasing company as soon as the construction began and then leased the ship to the shipping company under a bareboat charter. At the end of the leasing contract there was a commitment for the grouping to purchase the vessel while the shipping company undertook to buy it at the end of the bareboat charter.

Essentially, this complex setup generated tax benefits at the level of the grouping investors, who then transferred some of these benefits onto the level of the shipping company in the shape of a discount on the price of the vessel agreed by the shipyard.

Back in 2006, the European Commission received a number of complaints regarding the scheme and, consequently, they argued that the objective of the scheme was to grant tax advantages to the groupings and the investors participating in them, which then passed on part of the benefits to the shipping companies that bought a new vessel.

In 2013, the Commission declared the law partially incompatible with the internal market, finding that three out of five fiscal measures provided by the system constituted illegal State aid and maintaining that the law had been unlawfully implemented by Spain since January 1, 2002.

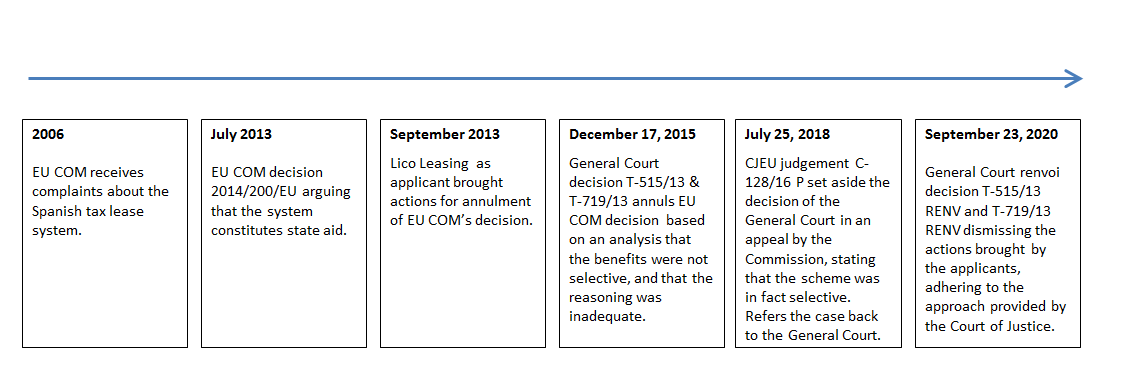

The development of the case has been equally complex, so for the sake of the overview and this update on the most recent development, a timeline is provided below.

Who are really the beneficiaries – intermediate or final?

Keeping in mind the complexity of the scheme, determining who really benefits from it has proved to be quite the challenge.

According to the Commission, the scheme constituted state aid incompatible with the internal market. Spain, on the other hand, argued that the groupings were transparent for tax purposes as they passed on the benefits to their investors, and since any investor from any sector of any size could invest in the groupings, the measure was not selective.

Fundamentally, the tax advantages are derived from the five fiscal measures applicable to finance leases (accelerated depreciation and — with authorization — early depreciation of certain goods), incentives for the groupings and to maritime shipping activities, the latter of which are already eligible for a very favorable tonnage tax state aid regime on their income from shipping activities.

In a 2015 judgment, the General Court annulled the Commission’s decision on the grounds that the measure was not selective.

This ruling was part of a series of decisions from 2014-2015 in which the General Court advanced a novel approach to determining whether a tax derogation or exception was selective.

In essence, it held that an exception from a tax system was not necessarily selective if it was open to any undertaking wanting to benefit from it.

Also, the General Court asserted that insofar as the Commission aimed to prove that the derogation or exception was selective, it was obliged to demonstrate that it was only available to some rather than all undertakings.

The issue of selectivity

The Court of Justice scrapped this approach by the General Court in a string of rulings, including a ruling in the Spanish Tax Leasing case in 2018.

It stated that, regardless of whether a derogation or exception was open to any undertaking from any sector, it was still selective if it differentiated between undertakings in a comparable situation.

The end result is that the Commission’s decision was not vitiated by a failure to state reasons. It was not obliged to identify the undertakings that were explicitly excluded from the measure in question.

The Court of Justice simply held that the General Court misapplied the provisions of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Article 107 relating to state aid in its analysis of the selective nature of the tax measures.

Selectivity can arise at many levels, and the mere fact that a benefit appears to be general at one level does not guarantee that it is not selective at another.

Even if the measure is open to all undertakings, it is still selective if it differentiates between participating and non-participating undertakings. In this regard, the Commission simply needs to establish that the measure is a derogation from the reference system and that this derogation cannot be justified by the nature or internal logic of that system.

In the Spanish tax leasing scheme, the groupings were obviously undertakings that obtained an advantage in comparison to other undertakings which may have wanted to buy a ship.

According to the Court of Justice, the fact that these benefits were passed on to the shareholders of the groupings is irrelevant.

Finally, the Court found that the tax lease system affected trade and adding this to the conclusion that the system was selective; it annulled the judgment of the General Court.

Ultimately, the Court of Justice ended the tug-of-war between the Commission and the General Court, and since it did not find that the state of the proceedings enabled it to give final judgment, it referred the case back to the General Court.

The renvoi judgment by the General Court

By its judgment of September 23, the General Court dismissed the actions brought on by Spain, adhering to the approach provided by the Court of Justice.

In terms of the selectivity, the General Court reviewed the case law stemming from the discretionary power of the national authorities when exercising their competences in relation to taxation.

This is an interesting addition to the ruling of the Court of Justice, stating that a measure is selective, even if it is in principle open to all undertakings when it differentiates between participating and non-participating undertakings.

This part of the ruling from the Court of Justice from 2018 may be criticized for posing a latent risk of undermining the principle of tax autonomy of the Member States.

Simply put, despite the acknowledgment of the freedom of the Member States to design their own tax systems while ensuring that they do not contain state aid, the Court of Justice does not necessarily acknowledge that tax systems must comprise exceptions of general application.

These exceptions can have policy objectives and function as tools for beneficial behavioral changes, and by classifying exemptions of general application as selective as such, the EU law inevitably encroaches on the prerogatives of the Member States.

In assessing the selectivity of the Spanish tax lease scheme, the General Court observed that the benefit was granted by the tax authorities in the context of a system of prior authorization on the basis of vague criteria requiring an interpretation for which no provision was established.

The result is that the tax authorities could set the start date for depreciation based on terms that granted them a considerable scope for discretion.

In short, the wide scope for discretion was in favor of the beneficiaries in comparison to other taxpayers in a comparable legal and factual situation.

In view of this de jure discretionary nature of the scheme, it was irrelevant whether or not the application was de facto discretionary. With this analysis, the General Court provided some sort of quantification of the approach by the Court of Justice.

The end result is that since the authorization of accelerated depreciation was one of the measures enabling benefits from the tax lease system, which was selective as a whole, the consequence was that the Commission had been correct in considering that the system as a whole was selective.

Furthermore, the General Court found that since the market for trading maritime vessels was open to trade between the Member States and since a price reduction of 20-30% of the price threatened to distort completion on that market, the relevant conditions were satisfied.

Consequently, the General Court disregarded the plea alleging disregard of the classification of the measure as state aid.

No recovery because of legitimate expectations?

According to the procedural regulation, recovery of unlawful state aid is not required if this would be contrary to a general principle of EU law, such as legitimate expectations.

The scope of this principle is very narrow as it merely applies to communications from EU institutions, and the Court of Justice has ruled continuously that companies must keep updated on the EU official journal for notifications of the aid, i.e. if no notification is made, legitimate expectation is absent in principle.

To deviate from this narrow interpretation, very specific circumstances must apply, and in relation to the Spanish tax lease scheme, the General Court found that it had not been established that the applicants had obtained precise, unconditional, and consistent assurances from the Commission that the regime did not constitute state aid.

Furthermore, the Court found that the Commission had, in fact, taken into account the requirement of legal certainty in its decision, which had led it to limit the recovery of the unlawful state in time.

Finally, the General Court rejected alleged infringement of the principles applicable to recovery.

The Commission had ordered recovery from all investors in the grouping despite the fact that some of the benefits had been transferred to the shipping companies.

The Court found that since the shipping companies were not considered beneficiaries of the aid, the Commission was right in ordering recovery of all aid, as it was the investors who benefitted from the aid since the scheme did not require them to pass part of the aid to third parties.

Be the first to comment