By Susi Baerentzen, Industrial Ph.D. Student at Innovation Fund Denmark

The OECD on July 9 provided data on no less than 4,000 multinational enterprise groups headquartered in 26 jurisdictions, operating across more than 100 jurisdictions worldwide.

This is an important development in terms of data on multinational enterprises, BEPS, and their activities.

The OECD/G20 base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) project has been one of the most significant overhauls in the history of international taxation, with 135 jurisdictions collaborating to tackle tax avoidance strategies by multinationals that exploit gaps and mismatches in the international tax rules.

In other words, the project works to ensure that taxes be paid where value is created.

So does the BEPS project ensure that taxes are really paid where value is created? And is it growing the revenue pie for the participating jurisdiction?

We are all eager to know, but assessing the effects and impact of the project is challenging for several reasons, particularly the lack of data.

Country-by-country reporting of multinational groups was implemented as part of Action 13 of the BEPS project to aid in solving this problem and to support jurisdictions in countering BEPS behavior.

What is the data telling us?

All multinational enterprise groups with revenues above EUR 750 million are required to annually submit country-by-country reports. These reports collect important information on where the enterprises do business, their global allocation of income and taxes paid, just as they feature certain indicators of the local economic activities and the business activities for each entity.

All of this data is vital to understanding the behavior of the multinationals and the taxation of their activities.

These country-by-country reports provide tax authorities with the information needed to analyze the behavior of the multinationals for tax risk assessment purposes, and the release of today’s anonymized and aggregated statistics will support the improved measurement and monitoring of BEPS.

For the first time, the data collected also contain information on BEPS Action 3 on controlled foreign company rules, and Action 4 on interest limitation rules, which are crucial to monitor the progress of the implementation of these rules and their impact.

And it is a fascinating read indeed because there are “plenty of signs in the data that point to continued BEPS,” notes Pierce O’Reilley, OECD Tax Economist on Twitter:

2. Does this mean that the CBCR don’t say anything about BEPS? No! There are plenty of signs in the data that point to continued #beps

— Pierce O’Reilly (@PierceOReilly) July 8, 2020

Location of tax accrued and location of indicators of economic activity do not align

One of the main findings of the report is that there is a misalignment between the location where profits are reported and the location where economic activities, like jobs, assets, and sales, occur.

One of the main findings of the report is that there is a misalignment between the location where profits are reported, and the location where economic activities, like jobs, assets, and sales, occur.

In other words, the profits are not being reported where the value is created, meaning that this is also not where the tax is paid.

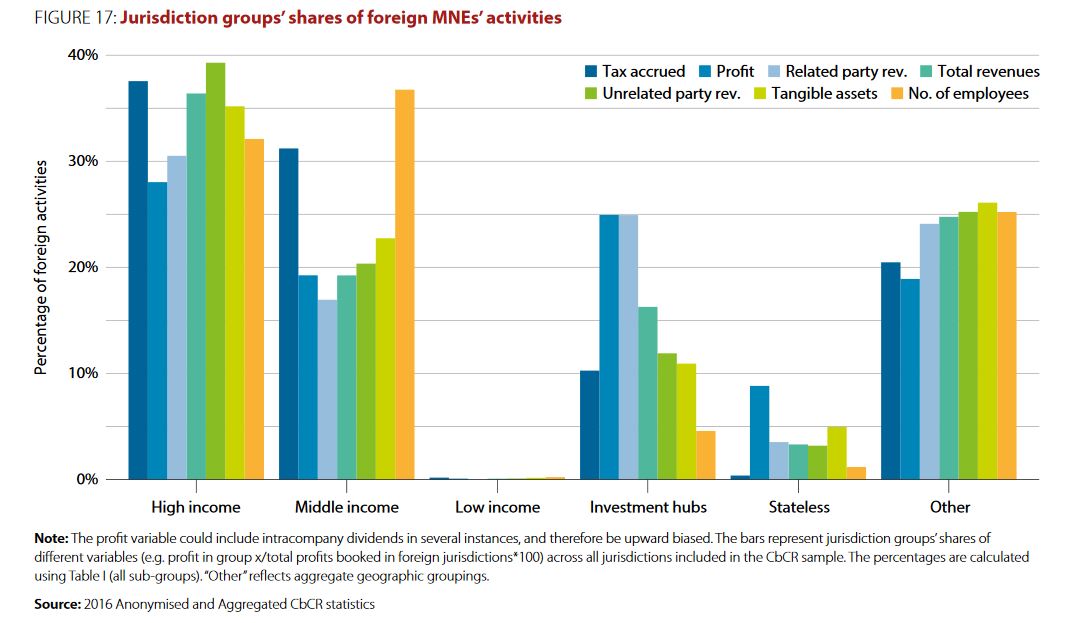

Multinationals in investment hubs report a relatively high share of profits compared to their share of employees and tangible assets, which underscores this misalignment, as illustrated by Figure 17 in the report:

Revenues per employee tend to be higher in jurisdictions with zero percent statutory corporate income tax rate

In other words, more revenue is generated relative to the number of employees in jurisdictions with a zero percent rate and in investment hubs.

This may indicate differences in capital intensity or worker productivity, but it can also be a high-level indicator of base erosion and profit shifting.

For multinationals in investment hubs, the share of related party revenues in total revenues is higher

It may be commercially motivated that the share of related party revenues is higher in investment hubs than in high-, middle-, and low-income jurisdictions.

However, these findings are also a high-level risk assessment factor and one that could indicate tax planning.

This goes hand-in-hand with the finding that in high-, middle- and low-income jurisdictions, sales, manufacturing, and services are the most prevalent activity, while in the case of investment hubs, the predominant activity is “holding shares and other equity instruments.”

Such a concentration of holding companies in investment hubs may relate to genuine commercial arrangements, but it is also a risk assessment factor and could be evidence of certain tax planning structures.

Such a concentration of holding companies in investment hubs may relate to genuine commercial arrangements, but it is also a risk assessment factor and could be evidence of certain tax planning structures.

Outlook

No matter the number of caveats in the OECD release, the country-by-country reporting data does provide a high-level risk assessment tool for tax authorities.

Taxpayers, on the other hand, are faced with difficulties associated with the sourcing of data within the multinational groups, and the burdensome required systems upgrades.

These challenges are exacerbated by the fact that the data and many items of information included in the reporting template were not collected or aggregated before the introduction of the obligation, and retrieving them now can be very challenging.

This also factors in the difficulties for the tax authorities with interpreting the data, and finally, it poses the risk that raw and potentially mishandled data can be released to the public and misinterpreted.

So, is it really all worth the effort?

On a high level, it appears that the data does indeed provide significant insight into the behavior of the multinationals and, consequently, into the impact of the BEPS measures.

While respecting the limitations of the data and duly noting that these observations could also reflect some commercial considerations, there are indications of BEPS behavior.

Ultimately this finding reinforces the debate on a need to continue the work in progress in the Inclusive Framework on Pillar 2 of the effort to address the tax challenges arising from digitalization.

From the view of the taxpayers, light is thrown on the intermediate structures employed by large multinationals, essentially exposing these structures and perhaps further necessitating revised requirements for adequate transfer pricing documentation as a result.

Be the first to comment