By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

The Mumbai Income Tax Appellate Tribunal ruled against the Indian tax authority on August 20 in Bennett Coleman & Co Ltd (As successor to Times Infotainment Media Limited) v. Deputy Commissioner of Income Tax. The litigation involved two questions regarding whether the funds to purchase Virgin Radio Holdings represented intercompany debt or equity. If the funds represented an intercompany loan from an Indian affiliate to a UK borrowing affiliate, then the pricing question becomes what represents an arm’s length interest rate.

On June 30, 2008, Times Infotainment Media Limited (TIML India) purchased Virgin Radio Holdings for £53.5 million. The acquisition of Virgin Holdings was made through TIML Golden Square, a UK subsidiary of TIML India. TIML India booked the transaction in its accounts as a loan to its UK subsidiary, but the interest rate on the loan was claimed at zero percent. The tax authorities argued that an arm’s length interest rate should be charged and that this interest rate should be based on the Bank of India’s prime lending rate. This rupee-denominated interest rate was 13 percent.

The taxpayer made two arguments. Its primary argument was that the £53.5 million in financing represented equity financing and not intercompany debt. The reason why the financing was labeled an intercompany loan was not clear. Action 2 of the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting initiatives noted the tendency for multinationals to engage in hybrid financing where the lending affiliate argues that it deserves no interest income on what effectively is equity, while the borrowing affiliate books an intercompany expense on the claim that the financing was intercompany debt.

The court decision does not discuss whether the UK affiliate booked intercompany interest expense on any of the financing. The UK tax authorities would certainly object to 100 percent of the financing being seen as intercompany debt. While hybrid arrangements are attempts at double no taxation, disagreements with respect to how much of this £53.5 million represented debt versus equity between the Indian and UK tax authorities could lead to double taxation.

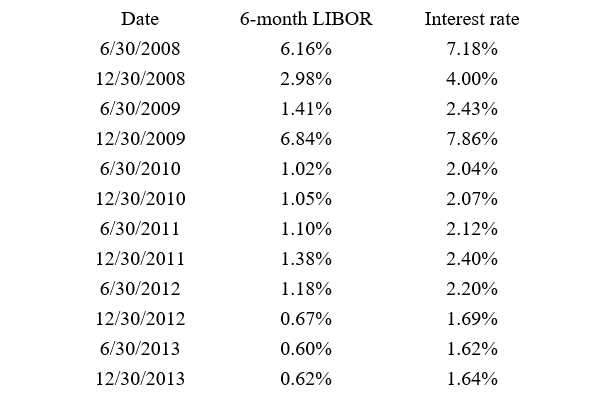

Table 1: Interest rates based on taxpayer’s position

Even if the two tax authorities agreed upon the mix of equity versus debt financing, the other issue is what represents an arm’s length interest rate. The taxpayer’s position was that the arm’s length interest rate should be based on the six-month LIBOR rate for floating rate loans based in pounds sterling plus a reasonable loan margin. The taxpayer also asserted that this loan margin should be 1.02 percent. On June 30, 2008, the six-month pound LIBOR rate was 6.16 percent, so the taxpayer’s position would suggest an initial interest rate equal to 7.18 percent. As table 1 shows, this LIBOR was lower for the subsequent anniversary dates, which would suggest lower interest rates under this interpretation of the arm’s length standard.

On June 30, 2008, the yield on six-month UK Treasury bills was 5.26 percent. The LIBOR to Treasury bill spread was then 0.92 percent, which was typical as financial markets were displaying significant stress as 2008 evolved. The credit spread implied by a 1.02 percent loan margin was therefore 1.94 percent, which would be consistent with an A-minus credit rating at the time.

The tax authority did not challenge the proposed loan margin as its assertion was that the appropriate currency of denomination should be the rupee and not the pound. In a 2013 article, I reviewed earlier intercompany loan litigations in India where the Indian tax authorities attempted to use the Indian prime lending rate for intercompany loans denominated in other currencies, noting:

Interest rates can be seen as being determined in a global marketplace, with differences in market-determined rates existing because loans have different characteristics with respect to the following:

-

- Date of the loan.

- Term or maturity of the loan.

- Currency of denomination.

- Borrower’s credit standing.

As noted below, the conflicting arguments between the various taxpayers and the Indian tax authorities indicate some apparent confusion regarding how to address the last two items on the list.

(“Indian Intercompany Loans Litigation”, Journal of International Taxation, June 2013.)

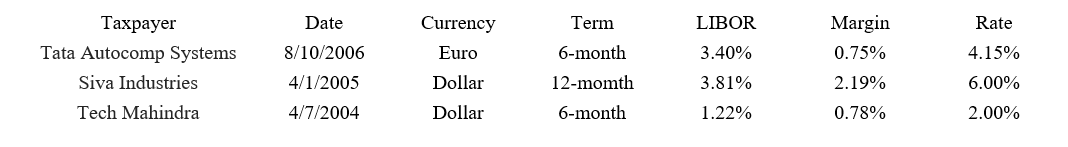

The tax authority tried to assert a high intercompany interest rate in subsequent litigations using the Indian prime lending rate in these earlier litigations, which included Tech Mahindra Limited v. DCIT, Siva Industries & Holdings Ltd. v. ACIT, and VVF Limited v. DCIT. Table 2 presents key information from these three litigations.

Table 2: Key information from three previous litigations

The 4.15 percent interest rate argued by the tax authority in the Tata Autocomp Systems litigation was consistent with the six-month Euro LIBOR rate for August 7, 2006, plus a loan margin equal to 0.75 percent. The 6 percent interest rate argued by the tax authority in the Siva Industries litigation was consistent with the 12-month dollar LIBOR rate for April 1, 2005, plus a loan margin equal to 2.19 percent. The 2 percent interest rate argued by the tax authority in the Tech Mahrinda litigation was consistent with the six-month dollar LIBOR rate for April 7, 2004, plus a loan margin equal to 0.78 percent.

If there was a clear intercompany contract for each of these litigations, the reported intercompany policies would be arm’s length if the assumed loan margin was consistent with the appropriate credit rating for the borrowing affiliate. Since the Indian tax authorities failed to challenge whether these loan margins were consistent with the arm’s length standard, the taxpayer prevailed in each litigation.

Similar issues arise where Indian parent corporations provide guarantees on behalf of their foreign affiliates who have taken out third-party loans. At first, the Indian courts did not require intercompany guarantee fees, but recent court decisions have noted that intercompany guarantees can be assessed, provided they do not exceed what would be charged under the arm’s length standard.

Be the first to comment