By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

Glencore won the latest round of its long-running transfer pricing dispute with the Australian tax authority involving the pricing of copper from the Cobar mines. In a November 6 decision, the Federal Court of Australia sided with Glencore in the Australian tax authority’s appeal of a 2019 trial court decision.

The decision was a significant blow to the Australian tax authority. According to former Australian Tax Office Deputy Commissioner Jim Killaly, if the Australian government loses further appeals, it should seek to amend its transfer pricing laws.

Killaly noted that the court might have concluded that a higher transfer price was required for Glencore’s Australian mining affiliate if the court placed more reliance on traditional transfer pricing structures than on third-party price sharing agreements. As will be discussed, this could be a successful argument for Australia in further appeals.

The essence of the Australian tax authority’s complaint was that an intercompany agreement between Glencore’s Swiss distribution affiliate and its Australian mining affiliate was altered in 2007, whereas the tax authority preferred the original contract.

Glencore emphasized that the new contract had risk-sharing properties that a mining affiliate might prefer. However, the Australian tax authority argued that the 23 percent discount under the new agreement was excessive and departed from an arm’s length standard. Thus, it shifted the Australian mining affiliate’s profits to its Swiss affiliate.

Glencore’s structure

Under a 1999 intercompany contract, Glencore International AG acted as a Swiss distribution affiliate, receiving a 4 percent commission rate on copper sales from Cobar Management Pty Ltd, the Australian mining affiliate. Shipping and smelting were performed by third party entities, with the reimbursement ultimately paid by the Australian affiliate under the original transfer pricing policies.

In early 2007, the Glencore intercompany arrangement was altered such that the Swiss affiliate incurred the third- party smelting costs. The transfer pricing structure was changed to a price sharing agreement where the Swiss affiliate’s discount was increased to 23 percent.

In early 2007, the Glencore intercompany arrangement was altered such that the Swiss affiliate incurred the third- party smelting costs. The transfer pricing structure was changed to a price sharing agreement where the Swiss affiliate’s discount was increased to 23 percent.

The Australian tax authority asserted that the new intercompany agreement should be ignored and replaced by the prior agreement. The trial court and the appeals court both rejected this attempt to recast the intercompany contract for the 2007–2009 period.

Netback approach: selling, shipping, and smelting functions

The appropriate discount rate depends on the appropriate compensation for the Swiss affiliate’s functions.

The Australian tax authorities adopted a netback approach to implement its petroleum resource rent tax and its minerals resource rent tax. This approach evaluates the appropriate price for a mining affiliate as the revenues received from customers minus the arm’s length compensation for downstream activities, including the cost of shipping, processing, plus an appropriate gross margin for the distribution affiliate.

The Swiss affiliate was originally only responsible for the selling function, receiving a 4 percent commission rate. The selling costs for copper multinationals are generally near 2 percent of sales, which suggests that the Australian tax authorities could have argued for a 3 percent commission rate.

Shipping was performed by third parties, which was directly paid for by the Swiss affiliate. This expense was passed on to the mining affiliate through a freight allowance. The role of shipping was minor in this litigation, which we note below in reference to one of the third-party transactions used by the taxpayer as an alleged comparable.

Smelting was performed by third party entities and initially paid for by the mining affiliate. However, the 2007 revised intercompany arrangement made the role of smelting the central issue in this litigation.

The taxpayer’s case for the high discount rate relied on third party agreements, which may have serious comparability issues. The tax authority’s expert witness made an interesting analytical case that depended on various factors, including the expected cost of smelting and expected copper prices.

The taxpayer’s case for the high discount rate relied on third party agreements, which may have serious comparability issues. The tax authority’s expert witness made an interesting analytical case that depended on various factors, including the expected cost of smelting and expected copper prices.

In an earlier discussion (“Gross Margins for Mining Marketing Hubs: Applications and Critiques of TNMM”, Journal of International Taxation, January 2020), I suggested that the Swiss affiliate’s appropriate discount rate is equal to the sum of the third-party smelter’s margin (s) and the distributor’s gross margin. The smelter’s margin under arm’s length pricing should be the ratio of the cost of smelting and refining (Sc) relative to the price of copper (Cp), with the appropriate value of s = Sc/Cp.

Under the 1999 contract, the Swiss affiliate deducted the actual cost of refining and smelting and received a fixed gross margin equal to 4 percent. Under the 2007 contract, s represented the expected Sc relative to expected Cp.

A key argument made by the Australian tax authority was that market conditions during the 2007– 2009 period were fundamentally different from historical market conditions. Copper prices had risen dramatically. In addition, expected smelting costs may have been low relative to previous periods.

Copper price volatility

As noted by the Glencore appeals court, the price of pure copper was volatile during the years at issue. In 2006, the year leading before the revised intercompany agreement, the copper price reached “unheard of heights,” the court noted. Figure 1, below, shows the monthly price of copper from January 2003 to December 2017.

Figure 1: copper prices reported by the International Monetary Fund (global price of copper)

This figure shows both the volatility of copper prices and the copper price boom that began even before 2006. Over the 15-year period from January 1990 to December 2004, copper prices ranged from $0.60 per pound to $1.40 per pound averaging $0.965 per pound. Over the 15-year period from January 2005 to December 2019, copper prices ranged from $1.50 per pound to $4.50 per pound averaging $2.948 per pound.

Copper prices averaged $3.06 per pound during 2006 but fell during the early months of 2007 before rising to $3.65 per pound by October 2007. Copper prices since then have been highly volatile. Actual prices averaged $2.95 per pound from 2007–2009.

Expert witnesses for Glencore and the Australian tax authority had very different views on expected copper prices for 2007–2009. Glencore’s expert forecasted almost $2.30 per pound while Australia’s forecast, prepared by Brook Hunt, suggested lower prices, about $2.25 per pound.

Smelting costs and arrangements

Contracts between smelters and mines are priced in terms of treatment charges (TC) and refining charges (RC). Copper concentrate contracts offer a purchase price based on the London Metals Exchange price minus the TC or RC being used at the time.

Treatment charges were forecasted to be $60 per metric ton in 2007, while refinery charges were forecasted to be $6 per pound. How these charges are converted to total smelting costs per pound of finished copper is unclear, Brook Hunt noted that these charges translated into 15.4 cents per pound of copper.

The trial court noted how these charges are negotiated by market forces, which leads to significant volatility in prices. The trial court also noted the roles of spot prices versus long-term agreements as well as the role of price participation. Price participation clauses represent a form of risk-sharing between the smelter and the mine.

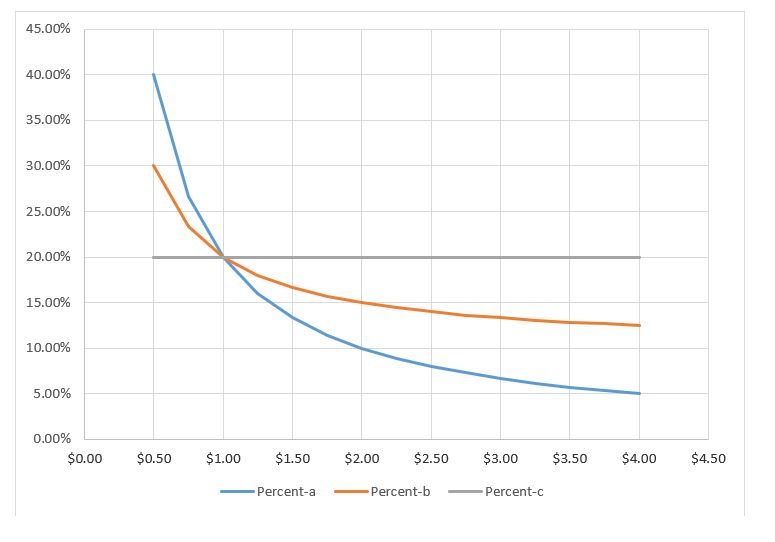

Table 1 explores the implications of a price participation contract, using as an example the copper market before the commodity boom where copper prices varied with a central tendency near $1 per pound.

Let’s also assume that during a normal period, smelters charged $0.20 per pound of finished copper, where the normal charge is $0.20 per pound, but this charge adjusts by 10 percent for any difference between the actual price of copper and our average $1 per pound.

Table 1: Effect on smelting costs under alternative contract types

|

Copper price |

Percent-a |

Percent-b |

Percent-c |

Cost-a |

Cost-b |

Cost-c |

|

$0.50 |

40.00% |

30.00% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.150 |

$0.10 |

|

$0.75 |

26.67% |

23.33% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.175 |

$0.15 |

|

$1.00 |

20.00% |

20.00% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.200 |

$0.20 |

|

$1.25 |

16.00% |

18.00% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.225 |

$0.25 |

|

$1.50 |

13.33% |

16.67% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.250 |

$0.30 |

|

$1.75 |

11.43% |

15.71% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.275 |

$0.35 |

|

$2.00 |

10.00% |

15.00% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.300 |

$0.40 |

|

$2.25 |

8.89% |

14.44% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.325 |

$0.45 |

|

$2.50 |

8.00% |

14.00% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.350 |

$0.50 |

|

$2.75 |

7.27% |

13.64% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.375 |

$0.55 |

|

$3.00 |

6.67% |

13.33% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.400 |

$0.60 |

|

$3.25 |

6.15% |

13.08% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.425 |

$0.65 |

|

$3.50 |

5.71% |

12.86% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.450 |

$0.70 |

|

$3.75 |

5.33% |

12.67% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.475 |

$0.75 |

|

$4.00 |

5.00% |

12.50% |

20.00% |

$0.20 |

$0.500 |

$0.80 |

Cost-a represents a fixed charge with no participation clause, while cost-b represents the impact on smelting costs with a 10 percent participation rate as copper prices rise.

Pricing sharing contracts, such as the one employed by Glencore, can be seen as extreme versions of price participation. The tax court noted the role of price sharing agreements, which establish the smelter charges as a percent of copper prices.

Cost-c in Table 1 shows the smelting cost under alternative copper prices if the smelter charge represents 20 percent of copper prices

As copper prices rise, the ratio of smelting costs to copper prices dramatically changes if smelter costs are fixed at $0.20 per pound, as shown in Table 1 and Figure 2 as percent-a.

Under a price participation clause, higher copper prices gradually increase smelter costs, which translates into a less volatile ratio of smelter costs to copper prices. This ratio is displayed as percentage-b in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Under our illustration of price sharing contracts, percentage-c remains at 20 percent regardless of copper prices. Note, however, that the smelter costs rise dramatically under a price sharing contract when copper prices increase.

The copper price boom led mining multinationals such as BHP Billiton to replace price participation clauses with fixed smelter price contracts.

The usual reason for this switch was that these mining entities did not want to pay smelter fees well in excess of the cost of smelting. Yet Glencore had its Australian mining affiliate sign an extreme form of price participation in the form of price sharing precisely during this period of time.

The usual reason for this switch was that these mining entities did not want to pay smelter fees well in excess of the cost of smelting. Yet Glencore had its Australian mining affiliate sign an extreme form of price participation in the form of price sharing precisely during this period of time.

The evidence presented showed that price sharing continued, but the price sharing percentages declined over time. An expert witness for the Australian tax authority noted that smelter costs relative to copper prices were 21.9 percent in 2002, 17.3 percent in 2003, 10 percent in 2004, 17.7 percent in 2005, and 15 percent in 2006.

This variability was in part due to changing copper prices but also in part due to fluctuations in the market. This expert noted that smelter costs in 2004 were only $0.13 per pound in 2003 but were $0.46 per pound in 2006.

An expert witness for the tax authority also asserted that if the parties entered a price share agreement in early 2007, the negotiations would likely start with a 8.1 percent rate rather than the 23 percent rate in the intercompany agreement.

Figure 2: Smelting costs relative to copper prices under three types of contracts

Application to the Cobar mine case

Brook Hunt’s forecast for smelting costs over the 2007–2009 period averaged 15.8 cents per pound while Glencore’s forecast averaged 19.2 percent.

If a reasonable forecast for smelting cost was 18 cents per pound and if we used the $2.25 per pound copper price forecast, then a reasonable estimate for s = Sc/Cp would be 8 percent.

Our estimate is roughly consistent with the starting point noted by the Australian tax authority’s expert.

Table 2: Expected v. actual smelting costs relative to copper prices

|

Per pound |

Forecast |

Actual |

|

Smelter costs |

$0.18 |

$0.18 |

|

Copper prices |

$2.25 |

$3.00 |

|

Percentage |

8% |

6% |

Note that even if we added a 3 percent premium for the value of the Swiss affiliate’s selling activities, the 23 percent discount is more than twice the expected cost of its functions.

Table 2 compares this estimate based on taxpayer forecasts to the actual percentage based on actual copper prices, which reached almost $3 per pound during 2007–2009. Given the uncertainty of future copper prices, it would be reasonable to set the price sharing ratio at 8 percent, even if the ratio of smelting costs to actual copper prices fell to only 6 percent.

While the Swiss affiliate reaped additional profits from this unexpected rise in copper prices, this arrangement put this affiliate at the risk of receiving lower profits had copper prices declined below $2.25 per pound.

Our analysis is consistent with the testimony of the experts for both the Australian tax authority and Glencore.

Under Glencore’s own forecast of copper prices and smelting costs, a 23 percent discount more than compensated the Swiss affiliate for its selling functions and the expected cost of smelting. The taxpayer, however, argued that third-party pricing sharing arrangements supported this new policy of using price sharing with a 23 percent discount.

Under Glencore’s own forecast of copper prices and smelting costs, a 23 percent discount more than compensated the Swiss affiliate for its selling functions and the expected cost of smelting. The taxpayer, however, argued that third-party pricing sharing arrangements supported this new policy of using price sharing with a 23 percent discount.

Glencore’s alleged third party comparable transactions

Glencore’s defense for the high price sharing percentage appears to be the percentages charged in six other pricing sharing arrangements.

One of these arrangements was between two affiliates of BHP Billiton. In late 2003, a Peruvian copper mining affiliate named Tintaya SA entered into an agreement with BMAG, which was given a 25.5 percent discount for smelting costs. The Peruvian tax authorities challenged this intercompany agreement.

Table 3 provides information on the other five agreements. The agreement involving PT Freeport Indonesia allowed for a rising price share for the smelter depending on copper prices, which is akin to how a price participation contract would be executed. The higher percentage was 27.5 percent.

Table 3: Summary of third party price sharing agreements

|

Date |

Mine |

Trader |

Rate |

|

Dec-01 |

Jiangxi Copper |

Glencore |

22.50% |

|

Oct-02 |

Tritton Resources |

Sempra Metals |

22.00% |

|

May-05 |

PT Freeport Indonesia |

PASAR |

21.00% |

|

Nov-06 |

Redbank Mines |

Glencore |

20.00% |

|

Jan-12 |

Red Earth |

Glencore |

21.00% |

The Australian tax authorities argued that the earlier contracts were not comparable to an agreement entered into during the beginning of 2007.

However, as discussed above, copper prices were fundamentally different before the commodity price boom as compared to 2007–2009, giving credence to the government’s comparability concern.

The Redbank agreement was established around the same time that the Glencore intercompany agreement was revised. This agreement provided a 20 percent discount for Glencore. The Redbank agreement had a comparability difference, though, because Glencore was responsible for freight charges. Glencore’s Swiss affiliate also paid for shipping of Cobar copper but passed this cost onto the mining affiliate in the form of a freight allowance.

The appeals court referred to this freight allowance, noting the cost of shipping to India was $60 per wet metric ton in 2009. Most of the shipments of copper from the Cobar mines were to China. The cost of shipment to China was lower than the cost of shipment to India. While a downward adjustment to the 20 percent discount in the Redbank agreement is warranted, this information is not sufficient to determine how much lower the adjusted percentage would be.

The appeals court concluded, however, that these third-party agreements establish that a price sharing agreement may have been entered into by third parties but offer little defense of the 23 percent discount.

The appeals court admitted that the comparability differences identified by the tax authority were relatively important with respect to the size of the appropriate discount. The appeals court agreed with the taxpayer that the third party agreements did establish that the type of pricing between the Swiss affiliate and the mining affiliate existed in third party contracts even if they did not confirm that the 23 percent discount was arm’s length.

The implicit risk and expected return argument

If the third-party transactions do not show the reasonableness of this 23 percent discount rate, one would imagine that reliance on an analysis that estimated expected economic costs would be a reasonable approach.

Our review suggests that this 23 percent discount rate is approximately twice the expected economic costs, even relying on the taxpayer’s estimates of copper prices and smelting costs.

The appeals court decision noted that the tax authority’s expert did not dispute that price sharing was a term legitimately used by parties dealing with each other at arm’s length; the concern was the 23% rate.

The tax authority asserted that the new agreement significantly lowered the revenues from the sale of copper concentrate with little in the way of compensation for this reduction. The expert witnesses for both the tax authority and the taxpayer conceded that the mining affiliate’s expected profits over the 2007 to 2009 period were reduced by this pricing sharing agreement.

While the tax authority viewed this issue in terms of maximizing expected profits, the taxpayer emphasized the role of risk aversion.

The taxpayer’s expert witnesses noted that the Cobar mine faced risks from high and rising production costs in addition to the risks from variable copper pricing and smelting costs.

Glencore’s experts emphasized the threat to the financial viability of the mining affiliate from potential increases in costs, while the tax authority asserted that the reduction in gross revenue from the 23 percent discount reduced the financial viability of the mining affiliate.

While a risk-averse company may trade off certainty for a modest amount of expected return, according to the appeals court, the “taxpayer had never demonstrated that these benefits justified giving up so much expected gross revenue.”

This central question parallels an issue in the litigation between the Canadian Revenue Agency and Cameco over uranium prices paid by its Swiss marketing affiliate to the Canadian mining affiliate, addressed in my MNE Tax article.

The structure of Cameco’s transfer pricing gave the mining affiliate only a modest return to its tangible assets and ignored the potential economic rent from being the lowest cost producer of uranium. One of the Canadian government’s expert witnesses estimated the value of this economic rent using Cameco’s forecasts with respect to uranium prices as they were expected to rise above the intercompany price.

Even though the Cobar mining affiliate may have had high operating costs, this affiliate would have received significant economic rents when copper prices reached $3 per pound.

A significant portion of these economic rents were shifted to the Swiss affiliate under the pricing sharing arrangement on the argument that the reduction in commercial risk compensated this affiliate for its loss of expected profits.

The taxpayer’s argument runs contrary to the popular notion that distribution affiliates incur limited risks. I would argue, however, that the bearing of commercial risks should allow an affiliate with at least a modest premium over routine returns.

To see this argument more clearly, think of economic rents as a form of intangible asset. While some tax authorities assert that licensees deserve only the routine return for their functions, financial economists would note that licensees deserve premium returns for bearing commercial risk.

This challenge to simple-minded approaches to intercompany royalties under the heading of the comparable profits method could be extended to the debate over the premium that a mining marketing affiliate should receive for taking on additional commercial risk.

Be the first to comment