By Dr. Harold McClure, New York City

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) began a dialogue with representatives of multinationals on how to address the transfer pricing implications from the demise of London interbank rates in an August 12 paper. This article builds on an example described in the ATO paper to further illustrate the issue.

The reporting of London interbank rates is scheduled to cease after December 31, 2021. Given the fact that many third party as well as related party floating rates loans use these rates as their base rate, an alternative base rate will be needed for existing loans as well as loans issued in the future.

Intercompany loans generally have either a fixed interest rate or a floating rate. Floating interest rate loans are also referred to as variable or adjustable rate loans. Floating rate loans are expressed in terms of a base rate plus a loan margin, where the interest rate varies over time with variations in short-term market rates.

As an example, consider a mortgage agreed in early January 2016 to pay the one-year US government bond rate plus a margin equal to 1.5 percent. At the time, the interest rate on one-year government bonds was only 0.6 percent, so the interest rate for the first year was 2.1 percent. The government bond rates on the anniversary date were 0.9 percent for 2017, 1.8 percent for 2018, 2.6 percent for 2019, 1.5 percent for 2020, and 0.1 percent for 2021. The adjustable rate mortgage contract would set the interest rate at 2.4 percent for 2017, 3.3 percent for 2018, 4.1 percent for 2019, 3.0 percent for 2020, and 1.6 percent for 2021.

Floating rate loans often use interbank offered rates as the reference point. The London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) has often been used as the reference rate. LIBOR rates currently are quoted for US dollar, UK pound, Euro, and Japanese yen-denominated loans and used to be quoted for loans quoted in other currencies, including the Australian dollar. LIBOR rates are quoted for US dollar-denominated loans where the rate changes every month, every three months, every six months, and year.

In early January 2016, the 12-month LIBOR rate for US dollar-denominated loans was 1.15 percent, which represented 0.55 percent spread over one-year government bond rates. Had the intercompany loan been established with the 12-month LIBOR rate as the base rate and a loan margin of 0.95 percent, the initial interest rate would have still been 2.1 percent.

The “TED spread” is formally defined as the difference between the 3-month LIBOR rate for US dollar-denominated loans and the interest rate on 3-month US Treasury bills. One can see the above 0.95 percent difference between the 12-month LIBOR rate and the one-year government bond rate as a longer term version of the TED spreads. Analogous TED spreads can be calculated for currencies other than the US dollar.

Credit spreads for fixed interest rate loans are defined as the difference between the interest rate on corporate bonds and the interest rate on government bonds for the same currency and the same term to maturity. For floating rates where the base rate is an interbank rate, the sum of the TED spread and the loan margin can be seen as the credit spread.

The August 12 ATO paper posed several examples of intercompany loans from an Australian parent corporation to a UK affiliate where the UK affiliate incurred intercompany pound-denominated debt with an interest rate equal to the 3-month LIBOR rate plus a 5 percent loan margin. Each of these examples addressed how the terms of the loan were altered after December 31, 2021.

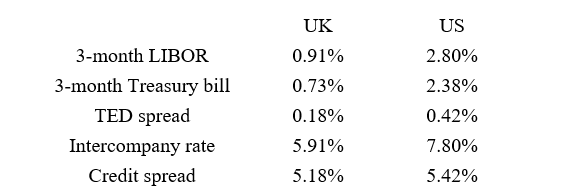

The following table considers the pricing of two intercompany loans, both issued in early January 2019. One loan was to a UK affiliate and was denominated in pounds, while the other loan was to a US affiliate and was denominated in dollars. The following table presents certain market data in order to determine the credit spread implied by a 5 percent loan margin.

Two hypothetical intercompany loans

The 5 percent loan margin in the ATO’s example is surprising in light of the intercompany contract at issue in Chevron Australia Holdings Pty Ltd v. Commissioner of Taxation. The tax court decision described the intercompany loan contract:

Central to the proceedings is a Credit Facility Agreement dated 6 June 2003 between CAHPL and ChevronTexaco Funding Corporation (CFC) under which CFC agreed to make advances from time to time to CAHPL “in the aggregate the equivalent in Australian Dollars … of Two Billion Five Hundred Million United States Dollars”. Interest was payable monthly at a rate equal to “1-month AUD-LIBOR-BBA as determined with respect to each Interest Period +4.14% per annum” and the final maturity date was 30 June 2008 (the Credit Facility Agreement).

The ATO challenged the 4.14 percent loan margin and successfully argued that this loan margin should have been less than 1.5 percent.

LIBOR rates were quoted in Australian dollars up to 2013 but have not been since. Interest rates on interbank loans denominated in Australian dollars, however, are still being reported. The interest rate on 3-month interbank loans denominated in Australian dollars was approximately 2 percent during early January 2010. Similar US rates were higher, while similar UK rates were lower.

The TED spread for US dollar-denominated loans was 0.42 percent. Had our intercompany loan been denominated in dollars with this 5 percent loan margin, the interest rate would have been 7.8 percent. As such the credit spread would have been 5.42 percent.

The TED spread for UK pound denominated loans was 0.18 percent. Had our intercompany loan been denominated in pounds with this 5 percent loan margin, the interest rate would have been 5.91 percent. As such the credit spread would have been 5.18 percent.

In the absence of reported LIBOR rates, an alternative base rate must be found. A simple solution might be to use Treasury bill rates as the base rate with the loan margin being equivalent to the credit spread. Our hypothetical intercompany loan could have been expressed as the Treasury bill rate plus a loan margin near 5.2 percent.

We shall note three caveats. The most important transfer pricing issue for this example is whether a credit spread in excess of 5 percent could be sustained as arm’s length. The ATO has challenged high credit spreads based on assumptions of weak credit ratings in situations where the related party borrower was an Australian affiliate. In this example, the related party borrower is a UK affiliate. It is likely that the UK tax authorities would challenge a credit spread in excess of 5 percent.

The second caveat relates to the fact that TED spreads vary over time. The US TED spread fell from over 0.4 percent in early January 2019 to less than 0.1 percent by the middle of August 2021.

Finally, one would need reporting of Treasury bill rates to execute our simple replacement for LIBOR. While the Federal Reserve reports US Treasury bill rates, the Bank of England recently ceased reporting UK Treasury bill rates.

Be the first to comment