By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

The Dutch tax authorities often challenge intercompany debt by claiming the financing should be considered equity. A July 16 Supreme Court decision in ECLI:NL:2021:1152 ruled in favor of the tax authority using the doctrine of fraudem legis (contrary to the aim and purpose of the law). A review of the terms of the intercompany loan will show that the Dutch tax authority could have also challenged the intercompany interest rate as being excessive.

A Dutch-based multinational acquired another entity for EUR 135 million, financed by almost EUR 75 million in equity and EUR 60 million in intercompany debt. This intercompany debt represented the financing provided by a sequence of French affiliates known as investment vehicles.

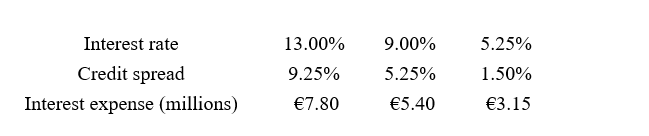

The intercompany debt was labeled convertible instruments, which had terms to maturity equal to 40 years and interest rates equal to 13 percent. The Supreme Court record also noted that a German entity had entered into an intercompany loan on January 31, 2011, with the same term to maturity but with an interest rate of 9 percent as this intercompany debt was not subordinated. If the interest rate equaled 13 percent, the Dutch affiliate incurred EUR 7.8 million in interest expenses per year. If the interest rate equaled 9 percent, the German affiliate incurred EUR 5.4 million in interest expenses per year.

A standard model for evaluating whether an intercompany interest rate is arm’s-length can be seen to have two components – the intercompany contract and the credit rating of the related party borrower. Properly articulated intercompany contracts stipulate the date of the loan, the currency of denomination, the term of the loan, and the interest rate. The first three items allow the analyst to determine the market interest rate of the corresponding government bond. This intercompany interest rate minus the market interest rate of the corresponding government bond can be seen as the credit spread implied by the intercompany loan contract.

On January 31, 2011, the interest rate on very long-term German government bonds was only 3.75 percent. The credit spread implied by a 9 percent interest rate was 5.25 percent, while the interest rate implied by a 13 percent interest rate was 9.25 percent.

Table 1: Key information for issue in ECLI:NL:2021:1152

Justifying this implied credit spread is the more difficult and controversial issue. The GE Capital Canada and Chevron Australia litigations highlighted the controversy with respect to estimating credit ratings. Both litigations highlighted the implicit support concept, while the Chevron Australia litigation specifically rejected the notion that intercompany debt should be seen as subordinated.

If the appropriate credit rating were BBB, then the appropriate credit spread would be only 1.5percent. In this case, the then arm’s length interest rate would be 5.25 percent and the intercompany interest deduction would be only EUR 3.15 million per year.

An earlier 2021 Supreme Court decision

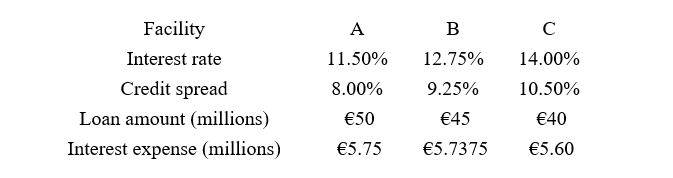

Table 2 summarizes the intercompany agreements addressed in a March 6 Supreme Court decision (ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2021:724). A Dutch multinational acquired another entity for EUR 322.7 million in early 2011. The acquisition was financed by foreign affiliates that extended EUR 135 million in intercompany loans, which were divided into three facilities with intercompany rates equal to 11.5 percent, 12.75 percent, and 14 percent depending on the facility. The date of these intercompany loans was January 31, 2011, and the term was 10 years.

Table 2: Table 1: Key information for issue in ECLI:NL:GHAMS:2021:724

On January 31, 2011, the interest rate on 10-year government bonds was 3.5 percent. As such the implied credit spreads were 8 percent, 9.25 percent, and 10.5 percent, depending on the facility. The taxpayer’s representatives provided the justification of what appear to be very high intercompany interest rates.

This “economic analysis” noted a third party secured loan from a syndicate of six banks where the third-party interest rate was lower than the interest rates noted in table 2. The analysis claimed that the intercompany loans were subordinated and would therefore deserve a higher interest rate than the third-party loan.

The analysis used a “Ratio-Inferred-Rating model” to suggest that the credit rating on a standalone basis should be CCC+. The analysis could not produce a Euro-denominated Bloomberg yield curve for this assumed credit rating but did manage to suggest its own extrapolation exercise that included rather arbitrary subordination premiums for each facility.

The tax authority questioned the reliability of the taxpayer’s justification. The tax authority’s approach, however, was also questionable. Using the 2010 average for three-month Euribor rates, which the tax authority claimed was approximately 1.5 percent, the tax authority argued for a 2.5 percent intercompany interest rate. On January 31, 2011, the three-month Euribor interest rate was only 1 percent, but short-term rates were generally lower than longer-term rates. While the tax authority suggested that the 10-year German government bond rate was 2.5 percent, this interest rate on January 31, 2011, was actually 3.5 percent.

The Supreme Court rejected the taxpayer’s aggressive position and its questionable justification. The Supreme Court ultimately accepted the position of the tax authority that the arm’s length interest rate should be 2.5 percent. The arm’s length rate, however, should be seen as the sum of the 3.5 percent government bond rate plus a reasonable credit spread. If the appropriate credit rating were BBB, then the credit spread would be 1.5 percent implying a 5 percent arm’s length interest rate.

A 2020 Supreme Court decision

A March 6, 2020, Supreme Court decision considered a similar issue, except the size of the intercompany financing was substantially larger (ECLI:NL:PHR:2020:102). A 2010 intercompany loan with principle equal to EUR 635 million was issued to a Dutch affiliate with an interest rate equal to 11.2 percent.

The Dutch tax authority argued that the arm’s length rate should be limited to 2.5 percent, which was the 10-year German government bond rate on August 30, 2010. While interest rates on 10-year German government bonds were generally higher during 2010, let’s assume that the intercompany loan was issued on August 30, 2010, with a term equal to 10 years.

An arm’s length interest rate should exceed the interest rate on the corresponding government bond rate by an appropriate credit spread based on the borrower affiliate’s credit rating. While a zero credit spread is too low, the 12.7 percent credit spread implied by the intercompany loan is clearly excessive.

Concluding comments

Arm’s length interest rates equal the interest rate on the corresponding government bond plus an appropriate credit spread, which depends on the credit rating of the related party borrower. The three Dutch litigations we reviewed had very high intercompany interest rates even though German government bond rates at the time were less than 4 percent in each case.

The tax authority in two of these litigations argued for a 2.5 percent interest rate even though the interest rate on the corresponding government bond rate was 2.5 percent or higher. The starting point of any economic analysis is the identification of the terms of the intercompany contract, including date, currency of denomination, and term to maturity. In each litigation, the currency of denomination was Euro, while the term was 10 years or more. The use of a short-term interest rate, therefore, makes no sense.

Interest rates on Euro-denominated notes today are much lower than they were a decade ago. Unless one can defend very high credit spreads, defending intercompany rates in excess of 10 percent is simply not credible. Litigations in other nations have stressed the role of implicit support, which would tend to suggest more moderate credit spreads.

The focus of many Dutch intercompany financing litigations has been on debt versus equity issues. Even if the intercompany financing issue survives this challenge from the Dutch tax authority, more attention needs to be paid on the pricing issue as to what constitutes an arm’s length interest rate.

Be the first to comment