By Susi Baerentzen, Ph.D., Carlsberg Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow, Amsterdam

On March 28, the High Court of Eastern Denmark delivered its ruling in two joined cases between the former A.P. Møller – Mærsk group—then Mærsk Olie og Gas A/S and A.P. Møller-Mærsk A/S (hereafter called MOGAS)—on one side and the tax authorities on the other.

The case concerns MOGAS’ participation in the initial phases of oil production activity in Algeria and Qatar and the know-how etc. that the company put at the disposal of its local subsidiaries for these preliminary investigations. The tax administration had conducted a discretionary assessment of MOGAS’ income as it found that the company had defrayed costs for its subsidiaries, which comprised controlled transactions, just as the transfer pricing documentation was disputed.

The High Court continued the recent line of court rulings rejecting the tax administration’s argumentation in cases about discretionary assessments. It stated that for the years in question (2006-2008), the initial investigative phase had been concluded, and expenses were no longer defrayed by MOGAS, i.e., the transactions in question were not controlled. The Court, on the other hand, did find that other performance guarantees and technical/administrative assistance provided for the subsidiaries were controlled transactions and should have been at arm’s length. Consequently, the case has been referred back to the tax authorities for a renewed assessment.

Facts of the case

MOGAS was a 100% owned subsidiary of A.P. Møller – Mærsk A/S (APMM), which was the management/administration company in the consolidated group. MOGAS, which was the parent company for a large number of subsidiaries, was incorporated in 1962 in relation to the current A.P. Møller – Mæersk group obtaining permission to explore and extract deposits of oil and gas in the North Sea. In 2018, Maersk Oil, which MOGAS was part of, was sold to Total S.A.

MOGAS’ activity consisted of three main areas until 2018: first, MOGAS was operator on behalf of the parent company APMM in the Danish section of the North Sea. In addition, MOGAS conducted preliminary investigations in different parts of the world to discover new oil fields, after which subsidiaries/branches were incorporated to facilitate the continued oil exploration and initiate the production of oil. Furthermore, MOGAS delivered a number of technical and administrative services (so-called time writing) for other companies within the group, including to APMM and to its subsidiaries in Algeria and Qatar.

Simply put, MOGAS conducted the necessary negotiations to obtain licenses with the local authorities, which was necessary to initiate the work to begin with. In this regard, MOGAS guaranteed that the obligations towards the oil state in question were met and that the contract with the relevant independent joint venture participants was fulfilled by the local MOGAS subsidiary or permanent establishment (so-called performance guarantees). MOGAS was paid at cost price for providing the time-writing services in the shape of technical and administrative assistance for the subsidiaries. If a license was obtained, the subsequent expenses were defrayed entirely by the subsidiary or its branch, and correspondingly, this subsidiary/branch received all the income from the oil extraction.

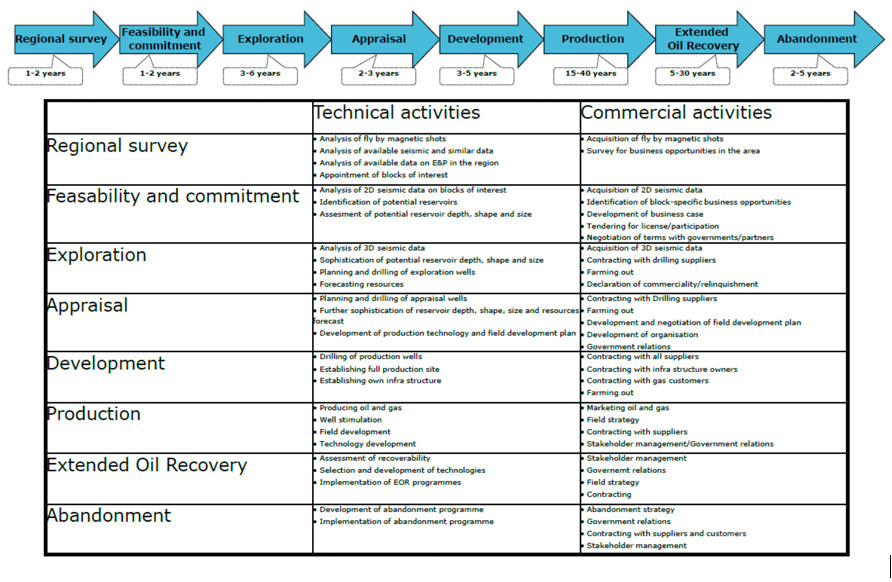

Looking at the overall lifespan of an oil production field, the initial investigative phases are relatively short, and the expenses are relatively low. The highly valuable and costly activities take place in the following explorative phases, which comprise drilling activities, that may very well turn out to be nothing. Only for the deposits that are likely to be commercially profitable to extract, infrastructure will be set up to perform this task, which requires very substantial investments.

The lifetime of an oilfield has been presented as follows in the case documents:

The issues in a nutshell

In 2012, the Danish Tax Agency had performed a discretionary assessment of the income for MOGAS for putting valuable know-how at the disposal of its subsidiary’s foreign branches in Algeria and Qatar. The Tax Agency had taken the view that MOGAS (in the years prior to incorporating the subsidiaries in Algeria and Qatar in the early 1990s) had defrayed expenses for preliminary investigations, which constituted controlled transactions for the income years 2006-2008. As mentioned above, the alleged know-how consisted among other things of initial preliminary investigations, the incorporation of subsidiaries, negotiations with the oil state, and the providing of performance guarantees and time-writing services.

The transfer pricing documentation MOGAS offered only comprised the providing of time-writing and not the expenses defrayed for the initial investigations or the providing of performance guarantees.

Essentially, the tax authorities had taken the view that MOGAS’ business model entails that the company will never be able to yield a profit from its activity because of the setup and that the presence of a group entity being persistently loss-making is an indication of further controlled transactions, which they were entitled to adjust. Consequently, the tax agency had adjusted the consolidated group income for the same income years.

In 2018, the Danish Tax Tribunal upheld those decisions, and MOGAS brought the case before the courts. The case was referred directly to the High Court.

Like several significant recent Danish transfer pricing cases, this case before the High Court fundamentally raises the question about whether there has been a basis for performing the discretionary assessment; and if so, if the assessment is being conducted on a faulty basis or is obviously unreasonable.

Ruling from the High Court

In determining whether there were controlled transactions at all, the High Court emphasizes that the subsidiaries in Algeria and Qatar both formally and actually owned the license rights to extract the oil for the income years in question, and therefore there were no controlled transactions.

The High Court considered it undisputed that the preliminary investigations in question were concluded in the early 1990s and that MOGAS did not defray further expenses for the subsequent phases of the oil extraction. Therefore, the preliminary investigations did not constitute controlled transactions for the income years 2006-2008. Based on the evidence provided, the High Court did not find a basis for concluding that remunerations in the shape of royalties or the like would have been paid for the preliminary investigations between independent parties, which would constitute a controlled transaction for the income years 2006-2008.

The Court further highlights that MOGAS has conducted similar preliminary investigations resulting only in a limited or even loss-making oil production, which the tax authorities have chosen to disregard. Furthermore, no examples were provided to show that payments are made in the shape of royalties or profit share in similar cases for the relatively limited work that is conducted in the initial investigative phases.

On the other hand, it follows from the annual reports for MOGAS for 2006-2008 that the company guarantees the obligations of the subsidiary through the performance guarantees, which varies over time and can involve large amounts. These guarantees were not mentioned in the transfer pricing documentation. The High Court did find that these guarantees for the subsidiaries in Algeria and Qatar were controlled transactions and, therefore, should have been determined at arm’s length. Furthermore, the Court found that the time writing provided for the subsidiaries in Algeria and Qatar at cost-price were not at arm’s length but should have been.

The transfer pricing documentation – significantly inadequate?

In assessing whether the transfer pricing documentation was so significantly inadequate that it did not provide the tax authorities with a sufficient basis for assessing whether the arm’s length principle was met—and therefore must be equated with a lack of documentation altogether—the High Court refers to the well-established principles in the Microsoft case from 2019 and the Adecco case from 2020.

In this regard, the High Court emphasizes that the fact that the tax authorities disagree with—or raise justified doubts about—the comparison analysis in relation to MOGAS’ delivery of time writing assistance does not, in itself, entail that the documentation is significantly inadequate. Furthermore, the Court did not find that the Ministry of Taxation had substantiated the significance of a potentially lacking or inadequate function analysis in the documentation for the determination of whether or not the arm’s length principle was met.

Assessment of the arm’s length terms – performance guarantees and time-writing

The High Court finds that the performance guarantees, which are controlled transactions, are not at arm’s length, and further finds that the Ministry of Taxation has substantiated that MOGAS’ supply of time-writing to its subsidiaries at cost-price is, in fact, outside the scope of what could have been achieved had the agreement been made between independent parties.

The Court’s conclusion

Overall, the High Court finds that although there is a basis for conducting a discretionary assessment of MOGAS’ taxable income for the years 2006-2008, the Ministry of Taxation’s assessment is based on a faulty basis and is obviously unreasonable. Consequently, the High Court referred the case back to the tax authorities for a renewed assessment. The same goes for the assessment of APMM’s consolidated income for the years 2006-2008.

Key takeaways from the High Court ruling

By rejecting the discretionary increase of the taxable income, the High Court adds to a line of cases following the same trend since the Microsoft Supreme Court ruling in 2019.

Essentially, the tax authorities have taken the view that MOGAS’ business model entails that the company will never be able to yield a profit from its activity because of the setup. This notion—that a group entity that is persistently loss-making is an indication of the presence of further controlled transactions—has been tried several times over to the tax administration’s detriment.

The High Court states here, once again, that the fact that MOGAS’ results for the period 1986-2010 have essentially been negative does not, in itself, provide an excuse for the tax administration to conduct a discretionary assessment.

When asked about the Eastern High Court ruling, Vice President and Head of Group Tax at A.P. Møller – Mærsk, Mette Mellemgaard Jakobsen, said:

“ We are pleased that the Eastern High Court has decided to follow the practice established by the Supreme Court, and ruled that our Transfer Pricing documentation was sufficient for SKAT to conclude on the arm’s length principle for the controlled transactions in the years in question.”

Thanks Susi B, brilliant