By Dr. J. Harold McClure, New York City

On December 17, the Federal Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the Australian Tax Office (ATO) in Singapore Telecom Australia Investments Pty Ltd v. Commissioner of Taxation. The issue involved what the ATO suggested was intercompany interest payments in excess of the arm’s length standard.

Background

Singapore Telecommunications Limited acquired Cable and Wireless Optus Pty Limited in late 2001. Singapore Telecom Australia Investments (STAI) became the operating affiliate financed by AUD 9 billion and AUD 5.2 billion in intercompany debt. The related party lender was Singtel Australia Investment Ltd (SAI), an affiliate in the British Virgin Islands.

The intercompany loans were in the form of a Loan Note Issuance Agreement (LNIA) entered into on June 28, 2002, and subject to three subsequent amendments. There were ten loans notes under the LNIA, which totaled AUD 5.2 billion and had an initial interest rate set at the one-year Bank Bill Swap Rate (BBSW) plus a 1 percent loan margin. This “applicable rate” was scaled up to account for withholding taxes. Given the complexity from the three amendments, our discussion will not incorporate the role of withholding taxes.

The first amendment was signed on December 31, 2002, and the second amendment was signed on March 31, 2003. These amendments maintained the floating rate nature of the intercompany loan. While the original agreement and amendments made the term of the LNIA ten years, it also allowed for the lending affiliate to redeem the loans on demand. The second amendment added an additional premium of 4.552 percent but also made the accrual and payment of interest contingent on certain benchmarks being met.

The third amendment was signed on March 30, 2009, and fundamentally changed the nature of the LNIA to that of a fixed rate agreement for the remaining four years under the LNIA. The stated fixed interest rate was 6.835 percent but also included a 1 percent premium as well as an additional premium equal to 4.552 percent. Even not factoring in the withholding tax considerations, the total interest rate for the last four years of the LNIA was 12.387 percent. The ATO’s objections to this complicated and ever-evolving intercompany financing focused on these last four years.

A standard model for evaluating whether an intercompany interest rate is arm’s–length can be seen to have two components – the intercompany contract and the credit rating of the related party borrower. Properly articulated intercompany contracts stipulate: the date of the loan; the currency of denomination; the term of the loan; and the interest rate. The first three items allow the analyst to determine the market interest rate of the corresponding government bond. This intercompany interest rate minus the market interest rate of the corresponding government bond can be seen as the credit spread implied by the intercompany loan contract.

This discussion notes the estimates of STAI’s credit rating and the testimony of Charles Chigas, who offered what might be seen as an ambitious but confusing discussion of the credit rating implied by the ever-changing nature of the LNIA. The court accepted the credit rating estimate from the taxpayer’s expert witness but rejected the Chigas report. The standard model noted above assumes a straightforward fixed interest rate loan contract. I offer a simpler interpretation of the third amendment to this rather complex and ever-evolving LNIA.

Credit rating

The group credit rating for Singapore Telecommunications was A+, which was relevant given that both the ATO’s and the taxpayer’s expert factored in the role of implicit support. Both experts testified that the standalone credit rating for STAI was BB on the date of the third amendment. They disagreed on the role of implicit support.

The ATO’s experts were Robert Weiss and Gregory Johnson of Global Capital Advisors. Mr. Weiss asserted a strong version of implicit support that would result in an estimate of the credit rating equal to A. This was the position of the tax authority’s expert witnesses in Alberta v. Enmax Energy Corporation (2018 ABCA 147). Weiss in that litigation testified as an expert for the taxpayer and had argued for a very poor credit rating in that particular litigation.

The taxpayer relied on Dr. William Chambers who also estimated that the standalone credit rate was BB. Dr. Chambers argued that the implicit support justified a credit rating closer to BBB-. His approach to the implicit support issue was similar to his testimony in General Electric Capital Canada v. the Queen (2009 TCC 563). The court accepted the approach of Dr. Chambers.

Period covered by the second amendment

The intercompany arrangement from June 28, 2002, to May 31, 2009, was a floating rate loan set at Bank Bill Swap Rate (BBSW) plus a loan margin. The loan margin was initially 1 percent but was raised to 5.552 percent on May 31, 2003.

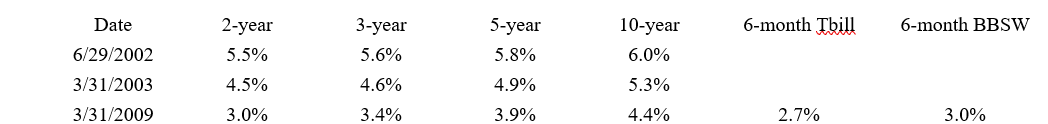

BBSW is an interbank rate. Interbank interest rates tend to exceed government bond rates by a modest margin. While the Reserve Bank of Australia reports interest rates on two-year, three-year, five-year, and ten-year government bonds dating back to 1976, its reporting of six-month interbank rates and six-month Treasury bills dates back to March 2009. Table1 presents key interest rates as reported by the Reserve Bank of Australia for both March 31, 2003, and March 31, 2009, as well as for June 29, 2002.

Table 1: Key interest rates as reported by the Reserve Bank of Australia

A 1 percent loan margin would not be excessive for a borrowing with a credit rating of BBB- but a loan margin in excess of 5 percent would clearly be excessive. The additional 4.552 percent additional spread would not have been warranted given the estimated credit rating in the absence of any considerations for the provisions that the accrual and payment of interest contingent on certain benchmarks being met.

The court noted that no interest was paid until April 2005. The court also noted that the total interest deductions over the entire period covered by the LNIA was approximately AUD 4.9 billion.

The Chigas report

Charles Chigas prepared a report that claimed that the effective credit rate over the life of the LNIA was only 1.44 percent, which he argued was lower than the credit spread that might reasonably be expected to have been agreed in an arm’s length debt capital markets (DCM) transaction between independent parties. Corporate bonds with credit ratings of BBB- tend to have credit spreads that are in excess of 1.5 percent. If this estimate of the effective credit spread was reliable, then this report would support the arm’s length nature of the intercompany financing.

Given the high loan margin under the second amendment and the high intercompany interest rate after the third amendment, this assertion that the effective credit rating was a mere 1.44 percent appears questionable. The court notes the approach taken by Mr. Chigas:

Mr. Chigas looks to the actual borrowing and payments over the ten years and assumes a traditional DCM transaction with deferred and capitalized interest. That requires him to adjust for the interest-free period and the fact that interest under the LNIA accrues only on the face value of the notes. He does that by working out the effective credit spread on the actual borrowing and actual payments having regard to the dates on which the actual payments were made. That calculation results in an actual credit spread of approximately 144 bps. He then applies this credit spread to the actual borrowing with assumed deferral and capitalisation of interest in a manner consistent with a DCM transaction in order to see what the transaction with the actual effective interest rate would look like. Thus, using the actual effective interest rate calculated by reference to the actual credit spread over the period of the loan he calculates what the semi-annual accrual and deferral/capitalisation of interest would look like.

One potential issue was how the credit spread was calculated. Credit spreads are defined as the difference between the yield of a debt instrument and the yield on a government bond where both instruments are in the same currency and have the same maturity. The court notes that Chigas relied on the following:

It is also common ground that the most economical, and likely only, source of debt in the amount of $5.2 billion for a term of 10 years for a party in the position of STAI was the US DCM in the form of a new issue transaction (coupled with a USD:AUD Cross Currency Interest Rate Swap (CCIRS)).

There are two possible biases with this approach. A ten-year government bond would tend to have a higher interest rate than a shorter-term government bond if the term structure was upward sloping, which was generally the case for Australian financial markets at the time. It is important to use interest rates appropriate for Australian debt instruments and not interest rates on US dollar-denominated instruments. Using swap rates is one mechanism for accomplishing the goal of having the currency of denomination be Australian dollars, but the use of swaps rates tends to overstate government bond rates by the swap spread. A simpler and less biased approach would have been to use the interest rate on Australian government bonds for the same maturity as the intercompany loan.

The court did note the following:

For each annual period, the table uses a “base rate” and adds the credit spread to determine the applicable interest rate for the period. For the base rate, the table uses the 1year BBSW for the years up to the year ending 31 March 2009 and 5.6143% for the subsequent years. The figure of 5.6143% was provided to Mr. Chigas by those providing instructions to him. Senior counsel for STAI said that the figure of 5.6143% came from an Australian Taxation Office schedule of calculations, and that it was a base rate that STAI had agreed to use. Senior counsel for the Commissioner then said that it is a figure which the Commissioner has accepted as a fixed rate from 1 April 2009.

The use of the one-year BBSW for the earlier years respects the floating rate nature of the LNIA under the second amendment but overstates the government bond rate if short-term government bond rates are less than the interbank rate. The use of 5.6143 percent is puzzling as this rate reflects Australian government bond rates as of June 29, 2002, which were substantially higher than Australian government bond rates as of April 1, 2009.

The court had a different issue with this approach:

The principal difficulty with STAI’s approach, in my respectful opinion, is that it departs too far from the actual transaction and the characteristics of the parties to that transaction … It did not involve a DCM bond issue. Further, I consider there to be significant differences between the terms of the LNIA and the terms of a typical DCM bond issue.

The court appears to be frustrated that the analysis did not reply on evidence from more comparable third-party loans. To be fair, however, the structure of the ever-evolving intercompany financing does not allow itself for a search of a truly comparable transaction.

The third amendment

Could an alternative approach to this issue be bifurcating the entire period into an analysis of the floating rate period prior to April 1, 2009, versus an analysis of a four-year fixed interest rate loan issued on April 1, 2009? The possible justification for such an approach comes from the court’s discussion of conversations between Singtel Telecommunications and their representatives at Ernst & Young.

In August of 2008, Singtel was concerned over the difficult financing situation that ultimately led to the Great Recession and the collapse of Lehman Brothers in the US as of September 15, 2008. Email exchanges from certain employees of Singtel and Ernst & Young suggested changing the intercompany agreement from a floating rate loan to a fixed-rate loan at an interest rate of 6.835 percent. The Ernst & Young emails interpreted this suggestion as this fixed rate plus a 1 percent premium subject to a transfer pricing analysis. The third amendment, however, based the fixed interest rate as the sum of 6.835 percent, the 1 percent premium, and another 4.552 premium.

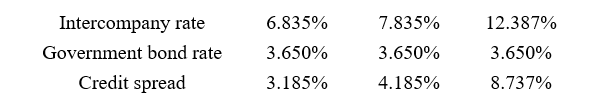

Table 2 considers three possible intercompany interest rates, including the original suggested interest rate with no premium, this rate plus a 1 percent premium, and this rate plus a total premium equal to 5.552 percent. Table 2 also assumes that the corresponding four-year government bond rate was 3.65 percent, which is an interpolation of the three-year and five-year government bonds rates as reported by the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Table 2: Implied credit spread for our interpretation of the third amendment

A credit spread in excess of 8.7 percent would certainly be excessive if the borrower’s credit rating were BBB-. Credit spreads in excess of 3 percent would also be seen as excessive for borrowings with investment-grade credit ratings in normal financial markets.

Credit spreads spiked during the period after the September 15, 2008, collapse of Lehman Brothers. I discussed the observed credit spreads for long-term corporate bonds rated BBB in “The Implications of the Credit Crunch for Intercompany Loans” (International Tax Review, February 24, 2009). On April 1, 2009, the interest rate on 20-year corporate bonds rated BBB was 8.38 percent, while the interest rate on 20-year government bonds was 3.54 percent. As such, the credit spread was 4.84 percent. Had the intercompany interest rate been only 7.835 percent, this interpretation of the intercompany financing would have supported its arm’s length nature.

The estimated standalone credit rating was BB. Had the court rejected the implicit support approach in favor of a standalone approach, the actual intercompany interest rate could have been supported by this alternative interpretation of the third amendment.

Concluding remarks

Our discussion has characterized the LNIA as two separate intercompany loans. The period covered by the second amendment was a floating rate loan with a high loan margin given the estimated credit rating under implicit support. Mr. Johnson as an expert witness testified that this loan margin was in excess of the arm’s length standard.

For the period under the third amendment, we have characterized the situation as a new fixed interest rate loan. The ATO was critical of this characterization with Mr. Johnson stating:

Even if an independent STAI had borrowed under the LNIA as amended by the Second Amendment, it would not have sought during the Global Financial Crisis to either refinance or convert a 100% floating rate financing into a 100% fixed rate financing of the same maturity 5 months before its next interest rate reset.

It is interesting that the LNIA claimed that the lending affiliate could redeem the intercompany loan on demand even though it also made the claim that the floating rate arrangement was a ten-year agreement. Refinancing in third-party arrangements exists but they are often the option of the borrower rather than the lender. While credit spreads in early 2009 were high, the credit spread implied by a fixed interest rate in excess of 12 percent would be excessive if the appropriate credit rating was BBB-.

The OECD transfer pricing guidance on financial transactions, released in February 2020, includes an extensive discussion entitled the “accurate delineation of the transaction”. While this discussion considers whether the tax authority can reclassify intercompany debt as equity, the ATO issue in the Singtel litigation accepted the debt nature of the intercompany financing preferring to challenge the pricing of the intercompany loan. If an intercompany contract is clearly and consistently articulated, its key features, including maturity and currency of denomination, should be respected.

The model for evaluating the arm’s length nature of an intercompany interest rate presumes a clearly articulated intercompany contract. If that contract represented a fixed interest rate loan, then a DCM approach is very straightforward. The problem in this particular litigation stems from the complexity and ever-evolving nature of the LNIA.

Be the first to comment