By Kuldeep Sharma, ADIT (CIOT, UK), Author ‘MLI Made Easy’, India

The consternation caused by unilateral measures taken by various countries on taxation of digitalised economies has been an area of immense concern for multinational corporations. Even before the introduction of these unilateral measures, it was only a matter of time before the UN and the OECD, which are at the vanguard of providing consensus-based solutions to the vexed issue of international taxation and transfer pricing, commenced work on taxation of digitalised economies.

The tax challenges arising out of digitalisation of economies were first identified as one of the main areas of focus of the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project, leading to the 2015 BEPS Action 1 Report. In March 2018, the Inclusive Framework, working through its Task Force on the Digital Economy issued ‘Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018’ which recognised the need for a global solution.

Substantial work has since been done by the OECD and the UN on taxation of digitalised economies. The OECD is at the brink of providing a solution based on consensus of its 139-member strong Inclusive Framework through a two pillar approach and has released blueprints on Pillar I and Pillar II.

On the other hand, UN has already inserted a new Article 12B in the UN Model for taxation of automated digital services.

In regard to implementation of the recommendations, there is on-going talk in the OECD and the UN that the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (MLI), emerging from BEPS Action 15, may offer a model for a coordinated and efficient approach to introducing these changes into the tax treaties.

FACTI panel report

Since UN has already inserted a new Article 12B in the UN Model, there is an urgency to roll out its implementation and an early adoption of the new provisions in tax treaties. The UN’s International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity for Achieving the 2030 Agenda (FACTI) panel released its report in February 2021 containing 14 main recommendations. Under Recommendation 2, the panel has inter alia observed at pages 17–18 as follows:

To hasten implementation, the UN Tax Convention should contain provisions holding that its terms will be automatically incorporated into signatories’ tax treaties, so that they would not need to renegotiate individual bilateral treaties.

In addition, under Recommendation 4A, the panel has inter alia observed at pages 24- 25 as follows:

Fair taxation of digitalised economic activity requires equitable treatment of digital businesses and business models with traditional business. The formulaic approach to taxing rights described above would help achieve this. To strengthen multilateralism, additional proposals to allow taxation of automated digital services should be adopted in the UN Tax Convention. Countries are already moving ahead with digital services taxes. Therefore, incorporating provisions to address this in the UN Tax Convention will create a multilateral framework based on international agreement and enable additional countries to start taxing the digital economy with realistic prospects of obtaining substantial revenue.

UN and OECD recommendations on digitalisation

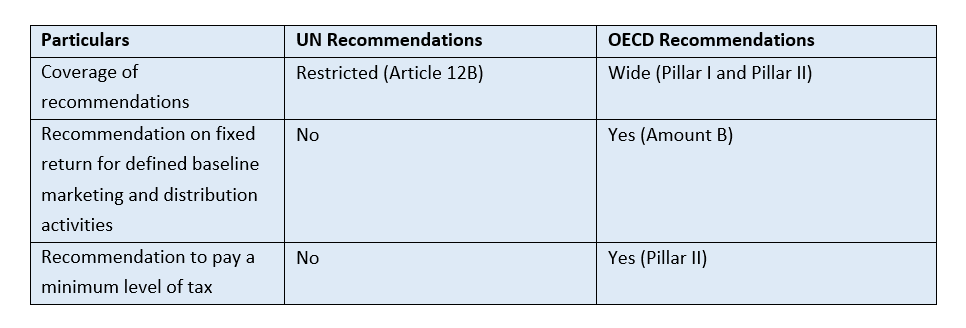

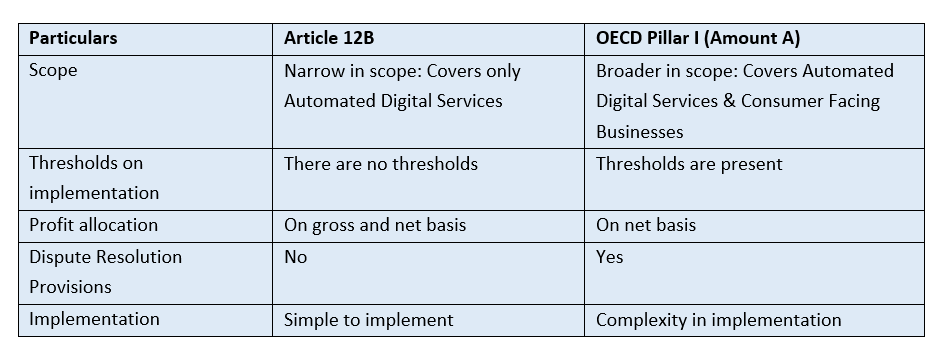

There are substantial differences in the recommendations of the UN under Article 12B and the OECD under Pillar I and Pillar II (consensus not reached yet). Article 12B of the UN Model broadly corresponds to OECD Pillar I (Amount A). Here is a bird’s eye-view of the comparative position of UN and OECD recommendations (without any comments on the merits and demerits of each proposal):

The circumstances under which OECD and UN have worked in the area of digitalisation can be summarised under three broad heads, namely, mandate, composition of taskforce, and support of Secretariat.

As far as mandate is concerned, OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS was mandated to produce reports on the Blueprints of Pillar I and Pillar II implying that G20 has specifically authorised OECD to carry out this task, whereas, no similar institutional mandate of international scale lies with the UN.

The Committee of Experts on International Co-operation in Tax Matters (UN Tax Committee) has worked on taxation of digitalised economies under its regular course of working as part of its 2017 to 2021 term. It is only now that the FACTI Panel in its report of February, 2021 provides that taxation of automated digital services should be adopted in the UN Tax Convention.

In regard to composition of taskforce, the OECD work on digitalisation is being carried out by the Inclusive Framework, consisting of 139 member jurisdictions which are represented by the government officials in their official capacity, whereas, the UN recommendations were made by the 25 member UN Tax Committee who are revenue officials but work in their personal capacity, although they are nominated by their respective governments. Quite clearly, the backing with Inclusive Framework is much stronger and participating officials hold governmental status vis-à-vis the UN Tax Committee wherein the numerical strength is much lesser and the revenue officials work in their personal capacity.

The support of Secretariat is very critical. The OECD Secretariat carries out the work of the OECD and duly supports the Inclusive Framework. It is led by the Secretary-General and is composed of directorates and divisions that work with policy makers and shapers in each country, providing insights and expertise to help guide policy making based on evidence in close coordination with committees.

The 3,300 employees of the OECD Secretariat include economists, lawyers, scientists, political analysts, sociologists, digital experts, statisticians and communication professionals. On the other hand, the United Nations Secretariat carries out the day-to-day work of the UN as mandated by the General Assembly and the Organization’s other main organs. The Secretary-General is the head of the Secretariat, which has tens of thousands of UN staff members working at duty stations all over the world. The Secretariat is organized along departmental lines, with each department or office having a distinct area of action and responsibility. Given the diversity in tasks performed by the UN Secretariat, its numerical strength to provide technical support to the UN Tax Committee is not quite substantial and focused vis-à-vis the OECD’s Secretariat. It is for this very reason that one finds that BEPS related amendments made in the UN Model Tax Convention were an adaptation of the BEPS related changes adopted in the OECD Model Tax Convention.

Conclusion

One may wonder as to why in the first place G20 mandated OECD to work on anti-BEPS measures and did not bestow that responsibility on the UN or any other international organization, namely, IMF and World Bank. My guess is that one of the many important factors influencing this decision is the strong technical support provided to Inclusive Framework by the OECD Secretariat.

As is evident, the technical support to the UN Tax Committee is not at par with that of Inclusive Framework. Article 12B in the UN Model is viewed as work of 25 committee members, though revenue officials, but working in their individual capacity. As against this, OECD’s recommendations on Pillar I and Pillar II are seen as participation in the Inclusive Framework of 139 government officials.

Going forward, as and when the Inclusive Framework succeeds in achieving the desired consensus and technical solutions on Pillar I, it is a certainty that these 139 countries would not be adopting Article 12B. The reason thereof is obvious.

Hence, it is expedient that first of all, the status of the existing UN Tax Committee may be upgraded to that of an intergovernmental committee. Under Recommendation 14B, the FACTI Panel has also inter alia made similar observations.

Also, the numerical strength of the UN Tax Committee needs to be increased so that at the policy making level itself more and more countries participate which shall ensure that the implementation of new provisions gets efficacious. In addition, the strength of the UN Secretariat for tax purposes may be substantially increased and upgraded. Academicians and experts from diverse fields of international taxation, transfer pricing, economics, law, scientists, statistics, communication professionals, etc. may be inducted.

It’s time for the UN to come out of the shadows of the OECD, make structural changes to its Tax Committee and strengthen its Secretariat to bring it at par with the OECD.

Otherwise, its recommendations of new provisions in the UN Model, if not aligned to the OECD recommendations, as is the case with Article 12B, may be difficult to get incorporated in any of the tax treaties.

If such structural changes are not implemented by the UN, the hard work of the UN Tax Committee (with the existing secretariat support) may remain academic only or at best, remain confined within a small network of tax treaties of developing countries. It is in the interest of developing countries also that the UN Tax Committee and its Secretariat remain robust and are seen as an alternative to the OECD.

Be the first to comment