By Ibrahim Moshood, Attorney, Centurion Law Group, Lagos

Following calls for the deregulation of the oil and gas sector in Nigeria, the National Assembly on 1 July passed the petroleum industry bill, which had been in the works since 2008. The tax changes introduced by the bill are expected to increase national revenue and create optimum opportunities for local and international investors alike.

The bill revamps the industry by amending at least ten different legislations that were hitherto applicable to the oil and gas industry.

We expect that the bill will receive presidential assent in the coming weeks and become fully operational.

In 2015, the present-day administration had split the bill into four separate segments: the petroleum industry governance bill, fiscal regime bill, upstream/midstream bill and the petroleum host communities’ bill. The petroleum industry governance bill gained prominence at that time and passed the Senate in 2019 but was declined the presidential assent needed to enact it.

In September 2020, the President presented the petroleum industry bill wholistically for consideration at the National Assembly, the result of which is the passage that was done by the Senate on 1 July.

Tax changes ushered in by the petroleum industry bill

The tax changes are contained in chapter 4 of the bill. The aim is to establish a fiscal arrangement to provide incentives for investors, clarity and increased revenue for the government.

The bill introduces a dual tax regime under which the Federal Inland Revenue Services (FIRS) is now to collect a hydrocarbon tax at 15%–30% on profits from crude oil production. This is in addition to the companies’ income tax at 30% and education tax at 2%. The hydrocarbon tax applies to crude oil, condensates and natural gas liquids from associated gas. However, it is not payable on associated and non-associated natural gas, condensates and natural gas liquids produced from non-associated gas in fields or gas plants regardless of whether the condensates or natural gas liquids are subsequently mixed with crude oil.

New hydrocarbon tax regime and rates

Since the bill has altered the tax regime from the Petroleum Profits Tax Act (PPTA) arrangement, there are some changes to the ascertainment of assessable profits of companies in the upstream sector. Some of these changes by the bill include new rules on deductible items, non-deductible items, and the minimum tax provision.

Regarding deductible items, expenses are now subject to the reasonability test, i.e., they must be wholly, reasonably, exclusively and necessarily incurred for hydrocarbon tax purposes. However, a cost price ratio limit of 65% of gross revenue is imposed, and excess cost incurred may be carried forward. Royalties are also deductible with respect to the final hydrocarbon tax payable after they have been paid and not on an accrual basis as under the Petroleum Profits Tax Act.

Bad debts, bank charges, penalties, natural gas and gas flare fees and education tax are not tax deductible. Other items, such as custom duties, head office, affiliates, and shared costs, are deductible for corporate tax purposes.

With respect to minimum tax provision, the deductibility of expenses and capital allowances for hydrocarbon tax purposes is subject to a cost price ratio at 65% of the gross revenue of the company in a given accounting year. However, rent paid on licenses, leases, royalties and other deductible taxes and levies paid to the government are not subject to the restriction.

To be eligible for a capital allowance claim, assets classified as capital work in progress are to be transferred to a more appropriate asset class and put to use. The costs of acquisition in a transfer of petroleum rights between related entities is also eligible for annual allowance at 10% for both corporate income tax and hydrocarbon tax purposes, and the tax written down value of 1% until the asset is disposed. Where such transaction is between unrelated entities, the acquisition cost is only eligible for corporate tax purposes.

Under the previous framework, a company could operate in more than one sector (upstream, midstream, downstream). Now a company intending to carry out operations in more than one sector must incorporate separate companies for each sector. The capital gains and stamp duties treatment in this situation appears to be different.

There has been an expansion of the list of companies eligible for the gas utilization incentives, as provided under S.39 of the Companies Income Tax Act. The list now includes companies in the midstream sector, including petroleum liquids/gas operations and large-scale gas utilization industries.

Companies are mandated to re-compute and file a revised estimated tax return whenever there is any switch in the price or volumes of condensates. The failure to do so results in the imposition of interest at London Interbank Official Rate (LIBOR) + 10% on the additional tax that would have been payable if the return had been submitted. The bill is silent on what would happen if a company fails to file a revised estimated tax return which results in a lower tax payable. Perhaps, the punitive measure only kicks in when the revised estimated tax return results in additional tax liability.

Late filing of tax returns will attract penalties of NGN 10 million (USD 19,802) on the first day and NGN 2 million (USD 3,961) for subsequent days of failure. Where no penalty is prescribed for an offence, a penalty of NGN 20 million (USD 39,603) is applicable – whether this is a one-time payment is not clear. However, penalties and fines are not tax deductible.

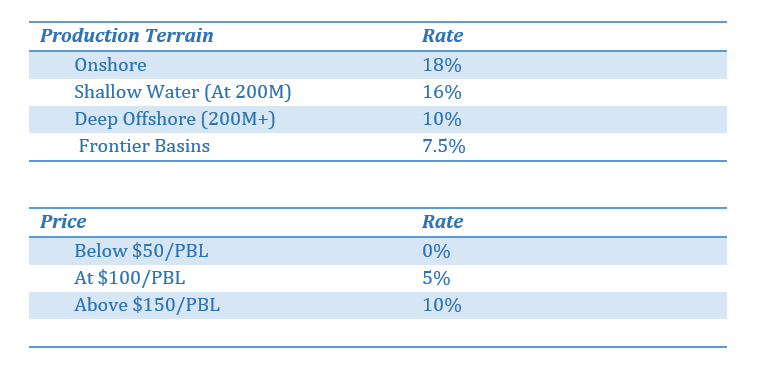

The bill retains the production-based royalty rates but has also introduced the price-based royalty, which is applicable based on price and production and is calculated on a field basis. The price-based royalties are credited to the Nigerian Sovereign Wealth Fund.

These changes are set to apply upon the following bases: conversion of existing oil prospecting licenses and oil mining leases to petroleum prospecting licenses and petroleum mining licenses, termination or expiration of licenses yet to be converted, and renewals of oil mining leases. This implies that holders of unconverted licenses and leases will continue to be taxed under the current regime of the Petroleum Profits Tax Act.

Conclusion

At a time when the world seems to be tilting towards cleaner and renewable energy sources, deregulating the oil industry is aimed at enhancing competitiveness. Now that the bill has been passed, it remains to be seen whether the fiscal provisions are competitive enough when compared to other jurisdictions.

If anything, it appears that the bill has further increased multiple taxation and has not successfully achieved true deregulation. But compared to the old regime, the bill is a positive stride towards shifting investors’ attention to the oil industry in Nigeria once again.

Impactful