Much has been written recently on the pros and cons of the proposed destination-based cash flow tax (DBCFT) from the House Blueprint on tax reform.

I will leave the broader argument to others who know those issues much better than I do. However, I would like to raise a critical comment on the apparent interaction of the proposed new tax as it would apply to partnerships and partners.

To tee up the pertinent issues, I would like to quote from David S. Miller’s paper (Tax Forum Paper No. 680, February 6, 2017) on the application of the subchapter K partnership rules to the DBCFT regime, which describes a situation that will likely come up frequently:

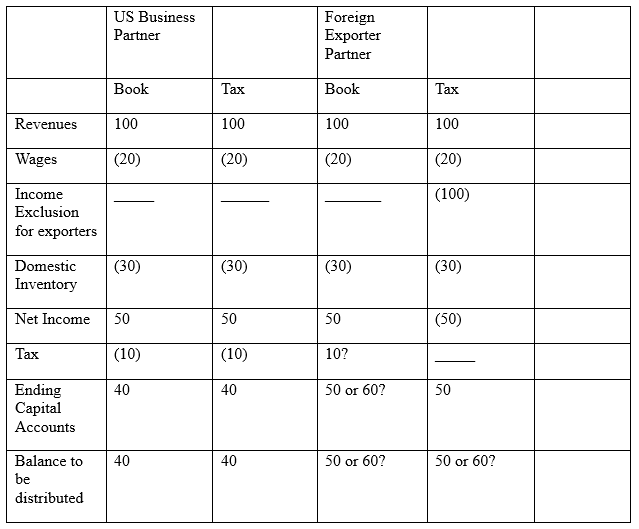

“Assume that a domestic partnership has two businesses: A domestic sales business and an exporting business. Each business earns revenues of 100, has wages of 20, and purchases domestic inventory of 30. Each business has pre-tax profits of 50. However, the export business generates a tax loss of 50, which is worth 10 based on a 20% tax rate. The domestic business has taxable income of 50 and pays tax of 10. On a combined basis, the partnership earns after-tax profit of 100. However, the domestic business pays tax of 10 and the exports business generates a loss of 50 (worth 10), so the combined business pays no tax…. Let’s assume that one partner is allocated all of the pre-tax economic income from the domestic business and the other is allocated all of the pre-tax economic income from the export business, and they agree to share the tax in accordance with relative profits. Since each business had the same pretax profit and, as a whole, the business paid no tax, they distribute 50 to each partner. . . . .Although this allocation would appear to have substantial economic effect under current law, I suspect that it wouldn’t be allowable under the Blueprint. The tax benefit exclusion of export income is intended for exporters. Only the partner who is allocated the economic income from exporting should be entitled to the tax benefits from that activity. The domestic partner should be distributed 40 and the exporting partner 60. It also becomes clear from this example that tax does not follow book under the DBCFT. Capital accounts are an economic income concept; the DBCFT is not. Likewise, the allocation of an exporting tax loss to a partner would not reduce that partner’s basis. Otherwise the exclusion would become a mere deferral.”

The allocation method set forth in the fact pattern described in the above scenario raises similar concerns as those present in the allocation regime under section 704(b) for creditable foreign tax expenditures (CFTEs). As a general rule, under the CFTE regime, the foreign tax follows the US net income related to that tax.

Example 25(i) and (ii) of reg. 1.704-1T(b)(5)[1] shows how the forced allocation of foreign taxes to related US net income can distort the partners’ economic deal. In such cases, though, the regulations basically say “tough” and that the partners can correct this distortion of their agreed economic deal out of other unrelated allocations.

In David Miller’s example, the partners wanted to split the net income $50 to each partner but the border adjustment regime appears to force the allocation to be $40 to the US side and $60 to the exporting side, a fundamental economic distortion of the partners’ deal.

If, as I expect, this type of regime is applied to the cash flow tax, it will add significant complexity to the US partnership tax rules, burdening small- and medium-size business and allowing only large partnerships with high level tax advice to deal adequately with the new tax system.

Add to this the added complexity from the House Blueprint’s partnership tax reform measures — which include separate income allocation categories at the partnership level for active business income; investment income; other income; the wages versus allocations on reasonable compensation issue; and the special rate of tax on corporations, whether partners or not — and you can see that this new system will be very very complex.

Taking David Miller’s example, adding in the Blueprint partnership reform proposals, and extrapolating a bit, here is what you get:

It seems that the only method that makes sense here is to charge the $10 of tax to the US side and carryover the $50 loss on the foreign side.

The economic equivalent of the $50 loss is a $10 accession to wealth, but there is no adjustment to the partnership book capital accounts that I know of that would make this adjustment. And so the capital accounts of the partners would add up to $90 but there would be $100 of cash to be distributed.

Now, the entire section 704(b) regulatory regime under reg. section 1.704-1(b) is turned on its head and a substitute regime needs to be put in its place. [2]

The loss should not be taken into account for tax purposes on the books of the partnership until it is used in a later year. Hence, carryover of a tax attribute (with no book corollary) appears to be introduced into the partnership tax regime.

One possible solution to carry out this scenario would be to give advance credit to the exporter partner for the $10 of net benefit of the tax loss that will be used (you hope) by the partnership in a future year.[3] That seems too far-fetched to me.

Stay tuned.

The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of either Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer & Feld or of any other firm or organization.

——————–

[1] Example 25. (i) A contributes $750,000 and B contributes $250,000 to form AB, a country X eligible entity (as defined in § 301.7701-3(a) of this chapter) treated as a partnership for U.S. federal income tax purposes. AB operates business M in country X. Country X imposes a 20 percent tax on the net income from business M, which tax is a CFTE. In 2016, AB earns $300,000 of gross income, has deductible expenses of $100,000, and pays or accrues $40,000 of country X tax. Pursuant to the partnership agreement, the first $100,000 of gross income each year is specially allocated to A as a preferred return on excess capital contributed by A. All remaining partnership items, including CFTEs, are split evenly between A and B (50 percent each). The gross income allocation is not deductible in determining AB’s taxable income under country X law. Assume that allocations of all items other than CFTEs are valid.

(ii) AB has a single CFTE category because all of AB’s net income is allocated in the same ratio. See paragraph (b)(4)(viii)(c)(2) of this section. Under paragraph (b)(4)(viii)(c)(3) of this section, the net income in the single CFTE category is $200,000. The $40,000 of taxes is allocated to the single CFTE category and, thus, is related to the $200,000 of net income in the single CFTE category. In 2016, AB’s partnership agreement results in an allocation of $150,000 or 75 percent of the net income to A ($100,000 attributable to the gross income allocation plus $50,000 of the remaining $100,000 of net income) and $50,000 or 25 percent of the net income to B. AB’s partnership agreement allocates the country X taxes in accordance with the partners’ shares of partnership items remaining after the $100,000 gross income allocation. Therefore, AB allocates the country X taxes 50 percent to A ($20,000) and 50 percent to B ($20,000). AB’s allocations of country X taxes are not deemed to be in accordance with the partners’ interests in the partnership under paragraph (b)(4)(viii) of this section because they are not in proportion to the allocations of the CFTE category shares of income to which the country X taxes relate. Accordingly, the country X taxes will be reallocated according to the partners’ interests in the partnership. Assuming that the partners do not reasonably expect to claim a deduction for the CFTEs in determining their U.S. federal income tax liabilities, a reallocation of the CFTEs under paragraph (b)(3) of this section would be 75 percent to A ($30,000) and 25 percent to B ($10,000). If the reallocation of the CFTEs causes the partners’ capital accounts not to reflect their contemplated economic arrangement, the partners may need to reallocate other partnership items to ensure that the tax consequences of the partnership’s allocations are consistent with their contemplated economic arrangement over the term of the partnership.” [Emphasis added]

[2] I am not suggesting a regime such that all allocations would have to be pro rata, much like S corporations, but that could be considered as a potential solution to this problem. But with the solution comes much pain, and in such a case the business and investment flexibility offered by partnerships would be sacrificed in order to implement the border adjusted regime which does not make a great deal of sense to me. It may to others though.

[3] An alternative would be to pass the loss through to the exporter partner and take the loss into account at the partner level in a later year, much like a section 743(b) adjustment. The allocation of the loss, as Miller points out in his Tax Forum paper, should not reduce outside tax basis because, otherwise, the tax benefit of the loss would be eliminated. The exporter’s outside tax basis should be $50 to account for the exporting revenue as tax exempt income. The exclusion of the exempt income could then occur at the partner level. This kind of regime seems even more complex than a carryover at the partnership level. S corporations would appear to have similar carryover issues as well.

Be the first to comment