By Oliver Treidler, CEO, TP&C GmbH, Berlin

The Transfer Pricing Economists for Development (TPED) in December 2019 published an intriguing study called the “Proposed Framework for Foreign Comparables Selection and Adjustment.”

The authors of the TPED study suggest that their findings could contribute to the technical implementation of the Pillar 1 OECD reform for taxing the digital economy, specifically the calculation of Amount B.

I disagree with their policy recommendations regarding Pillar 1. Instead, I believe the TPED proposal should be incorporated into the existing OECD transfer pricing guidelines.

Country risk profiles could facilitate a more pragmatic approach to benchmarking

The main goal of the TPED publication was to provide tax administrations of emerging and developing countries as well as MNEs operating in these countries with an economic framework for determining arm’s length transfer pricing arrangements.

There is no doubt that the absence of a sufficient number of reliable domestic comparable companies presents a core challenge for transfer pricing practitioners – especially when dealing with developing countries.

To a certain degree, these limitations are inflicted by the tax authorities, who insist on the use of domestic (national) comparables. Performing a so-called pan-regional benchmark analysis, namely, selecting comparables operating in geographic proximity to the tested party, will usually increase the number of available comparables and can often alleviate the problem.

Based on an empirical analysis, the TPED paper argues that even though such pan-regional studies are appealing and widely used in practice, a selection of comparables based on similar country risk profiles would be even superior.

Specifically, TPED proposes to integrate the country risk profiles of comparables as an additional component in comparability analysis.

In my view, the proposed analytical framework is largely consistent with the existing framework provided by the OECD and would, if adopted, greatly enhance analytical flexibility when performing benchmark studies.

The analytical framework proposed by TPED has the potential to facilitate a more pragmatic application of the arm’s length principle. While there remain some methodological and technical issues, transfer pricing practitioners should embrace the general idea and contribute to this welcome discussion.

Discussion should focus on improving existing framework not on Pillar One application

Aside from the primary focus on improving the framework for benchmarking, the TPED paper contains recommendations for contemporary tax policy.

Specifically, the TPED claims that their study could support and facilitate simplification of transfer pricing, such as reflected in the fixed returns for certain “baseline” activities recently suggested by the OECD in its Pillar One proposal. As will be discussed below, however, these policy recommendations seem to be somewhat misguided and inconsistent. Rather than supporting the Pillar One proposal, the framework proposed by the TPED would seem to support the notion that a pragmatic application of the arm’s length principle is feasible for developing countries. In any case, the analytical framework proposed by the TPED for benchmarking is sensible and should best be discussed separately form contemporary tax policy issues, which will only obscure and distort the discussion

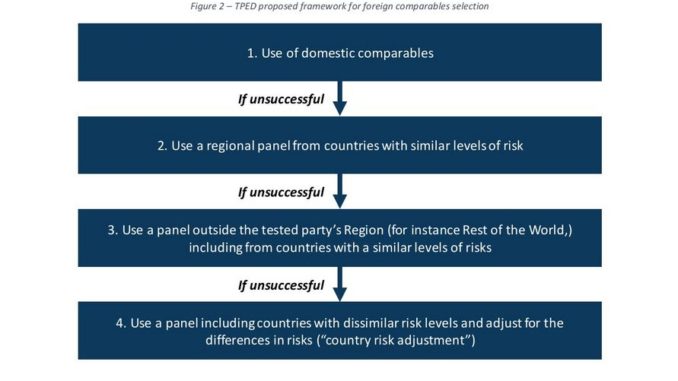

The following figure summarizes the TPDE proposal [page 13, Figure 2].

As can be seen, the selection of comparables based on country-risk is conceived as “step 4” and is (mostly) an add-on to the existing OECD framework for comparability analysis.

Aligning the TPDE proposal with the OECD Guidelines

The status quo in respect to the use of nondomestic comparables is captured by TPDE in pages 7 and 8 of the paper( emphasis added):

“in general, the arm’s length analysis is preferably based on domestic or regional data. […] Yet, in many countries, especially emerging markets, it is often impossible to retrieve such data due to the absence or scarcity of (reliable) financial information […]. Despite the complete absence or scarcity of domestic comparables, there is often a reluctance by tax administrations to accept foreign comparables, especially if such comparables originate from countries with differences in economic circumstances that are perceived as being substantial (e.g., comparables from “developed countries” used to benchmark companies located in “developing countries”).

The stubborn reluctance of tax administrations indeed presents a real problem for transfer pricing practitioners.

When we are talking about benchmarking and the application of the transactional net margin method (TNMM), the issues of tax avoidance or aggressive transfer pricing can, at most, be of secondary concern.

The BEPS potential for these transactions is limited, as we only deal with the quantification of a routine remuneration (for the tested party), rather than an allocation of the residual profit, which is by far the more potent lever for tax avoidance schemes and which was, rightly, the key target of the OECD BEPS reforms.

The TPED asserts that:

“Available transfer pricing guidelines, notably the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines or the U.N. Transfer Pricing Manual, do not necessarily provide a strict position on the usage and adjustment of foreign comparables” [see TPED page 8].

While the assertion is certainly sensible, it would require substantial qualification in case the proposed framework by the TPED was implemented outside the scope of the OECD transfer pricing guidelines.

Whether this is the intent of the TPED is not clear, but there are good arguments for embedding the proposed analytical framework within the existing OECD transfer pricing guidelines, which should facilitate a swift adoption of the framework.

Embedding the TPED proposal in the OECD guidelines

OECD transfer pricing guidelines 3.33 provides:

“The use of commercial databases should not encourage quantity over quality. In practice, performing a comparability analysis using a commercial database alone may give rise to concerns about the reliability of the analysis, given the quality of the information relevant to assessing comparability that is typically obtainable from a database. To address these concerns, database searches may need to be refined with other publicly available information, depending on the facts and circumstances. Such a refinement of the database search with other sources of information is meant to promote quality over standardised approaches and is valid both for database searches made by taxpayers/practitioners and for those made by tax administrations.”

Similar provisions are included in the domestic transfer pricing regulations of many countries. For example, in Germany, the respective administrative principles procedures (BMF-Schreiben v. 12.4.2005, section 3.4.12.4).

Thus, taxpayers are supposed to look at individual comparables to ascertain a sensible (sufficient) degree of comparability.

The TPED proposal (specifically Step 4 of the analytical framework) is, at its core, focused on using economic analysis to extend the pool of potential comparables.

As such, the approach is about enhancing the quantity of comparables without eroding the quality of the analysis and must consequently be viewed as consistent with respective provisions.

The OECD transfer pricing guidelines at 3.35 reads:

“Taxpayers do not always perform searches for comparables on a country-by-country basis, e.g. in cases where there are insufficient data available at the domestic level and/or in order to reduce compliance costs where several entities of an MNE group have comparable functional analyses. Nondomestic comparables should not be automatically rejected just because they are not domestic. A determination of whether nondomestic comparables are reliable has to be made on a case-by-case basis and by reference to the extent to which they satisfy the five comparability factors. Whether or not one regional search for comparables can be reliably.”

The existing OECD guidance seems entirely sensible and opens the door for performing pan-regional benchmarks.

It would also cover the use of nondomestic comparables that are identified based on country-risks considerations and thus constitute a sufficient basis for linking the TPED framework with the OECD transfer pricing guidelines.

The key point here, from a practitioner’s perspective, is that the existing guidance needs to be taken seriously by tax authorities.

The more pragmatic and flexible provision enacted by South Africa, referred to by the TPED [page 8], seems entirely sensible in this context and could serve as a best practices approach for other tax authorities.

Also, OECD transfer pricing guidelines 3.80 – 3.83 contain sensible guidance on compliance issues and limiting administrative burdens while not infringing legitimate interest of tax authorities in a transparent documentation of a comparability analysis.

In practice, the core difficulty seems to be unwillingness tax authorities to adhere to this guidance. The most immediate and direct alleviation of the problems (costs) connected to having to perform (multiple) comparability analyses, especially from the perspective of SMEs, is to put much more emphasis on the principle of proportionality and to require that tax authorities bear the burden of proof when assessing benchmark studies.

In sum, there seems to be no apparent obstacle for embedding the TPED proposal in the OECD transfer pricing guidelines.

In sum, there seems to be no apparent obstacle for embedding the TPED proposal in the OECD transfer pricing guidelines.

Naturally, the discussion with stakeholders, especially tax authorities, would need to address well-known issues that might contribute to the reservations against nondomestic comparables and benchmarking and TNMM in general.

First and foremost, this would seem to depend on reshaping the current discussion regarding facilitating consensus on two fundamental issues.

First, it is feasible, at least in most cases, to delineate routine from non-routine functions (i.e., functional and risk analysis based on the post-BEPS OECD transfer pricing guidelines 2017.

An arm’s length remuneration for routine functions can reliably be determined by one-sided methods, most notably the TNMM (CPM).

Second, when routine functions are clearly delineated, the application of the TNMM does not provide MNEs with an enticing lever for aggressive transfer pricing structures; i.e., the potential for shifting profits is much smaller in the context of calculating routine remuneration than it is in the context of allocating residual profits among entrepreneurial entities.

Hence, the regulatory framework and guidance for applying the TNMM and calculating routine profits should be less strict and emphasize the principle of proportionality.

The existing OECD transfer pricing guidelines, in my interpretation, reflect a clear consensus on these two basic issues.

That consensus seems to be increasingly diluted in contemporary discussions on digital taxation, which are often technically unsound and solely driven by politics.

Maintaining the focus on agreeing to key principles and on how to improve the application of the arm’s length principle would greatly help in sustaining clarity in an otherwise increasingly muddy discussion.

Interpreting country-risk in the context of transfer pricing

The basic assumption underlying the proposal of the TPED seems rather straightforward; namely:

“If, as suggested in literature, companies located in riskier countries are on average more profitable than their counterparts in less risky countries, the risk factor (proxied by the sovereign rating) may be used as a comparability criterion and a segmentation factor in the context of searches of foreign comparables outside the domestic country where the tested party operates.” [page 9]

While using the risk factor is intuitive and appealing, the link or (extent of) the correlation to the (expected) profitability of comparables could require some additional explanations to convince potentially skeptical stakeholders (tax authorities – see above).

While the work and data regularly published by Aswat Damodaran, who is referenced as an authority by TPED, are habitually used by transfer pricing practitioners in the context of analyzing financial transactions (i.e., determining risk spreads in down-notching procedures), it would be helpful to elaborate on the presumptions underlying the application of this work in the context of the TNMM.

Considering that this presumption will largely drive the results of the proposed framework, such explanations should not only have to be substantiated empirically but also need to be presented in a form that is likely to facilitate consensus among stakeholders.

The Damodaran paper cited by TPED illustrates that investors will, ceteris paribus, require a higher return on their investment when the country risk is higher and also touches upon the issue of differing equity risk premiums across countries for the valuation of companies.

How the credit default swaps relate to the remuneration for routine business functions is, however, not sufficiently clear and should be a focal point of future research.

Furthermore, some of the theoretical issues raised by Damodaran regarding the calculation and interpretation of country risk should also be explicitly addressed for transfer pricing purposes.

The most relevant aspects are, arguably, discussed by Damodaran in his Chapter on “Valuing Country Risk in Companies and Projects.”

His questing here seems to be of relevance to the empirical analysis of TPED; namely:

“If we accept the proposition that country risk is not diversifiable and commands a premium [as would seem to be implied in the presumption of TPED in using CDS as proxies], the next question that we have to address relate to the exposure of individual companies to that risk. Should all companies in a country with substantial country risk be equally exposed to country risk?” [see p. 84 of Damodaran Paper].

Both, the “operations-weighted ERP” and the “Lambdas” approach, discussed by Damodaran, caution against using uniform country risks for transfer pricing analysis purposes.

Damodaran conclusively demonstrates that the seat (registration) of companies alone is insufficient to explain exposure to country risk. Substantial differences in exposure to country risk may result from generating income in other countries (local distribution hubs).

Damodaran conclusively demonstrates that the seat (registration) of companies alone is insufficient to explain exposure to country risk. Substantial differences in exposure to country risk may result from generating income in other countries (local distribution hubs).

Also, Damodaran explains:

“Companies that would otherwise be exposed to substantial country risk may be able to reduce this exposure by buying insurance against specific (unpleasant) contingencies […]. A company that uses risk management products should have a lower exposure to country risk […] than an otherwise similar company that does not use these products” [see p. 89 of Damodaran Paper].

Similar arguments could be made for routine companies within an MNE value chain. TPED seems to be aware of these issues and might want to integrate specific solutions when refining the empirical analysis.

While addressing these issues seems to be required to substantiate the basic premises – and it is certainly worthwhile to do so – it is also clear that the simplification and accuracy promised by the TPED approach may not be substantial.

This does not need to detract from the advantages to transfer pricing practice, but the TPED needs to balance the required degree of accuracy with the increase in complexity.

Also, if the proposed framework is embedded in the OECD transfer pricing guidelines and step 4 is merely an add-on to the existing framework, the demands of stakeholders in respect to “accuracy” would presumably be lower compared to a proposal focused on promoting step 4 on a stand-alone basis.

Reviewing analytical method and results of the analysis presented by TPDE

The restricted scope of the analysis, limited to the food processing industry, is certainly appropriate for this stage of the discussion, but it also seems clear that the scope needs to be extended to substantiate the indicative conclusions.

More importantly, the statement that the analysis “comprises data from 1,042 independent companies operating in the food processing industry worldwide. Companies operating in the food processing industry can be considered relatively homogenous in terms of functions, assets and risks” [pages 10 and 32] needs to be revisited and requires detailed and careful qualification.

What exactly is meant by the “relatively homogenous composition” of comparables? Are these comparables all deemed to be routine entities that are assumed to exhibit a limited functional and risk profile (i.e., to ensure comparability to the tested party, which “by default” should have a comparatively simple functional and risk profile)? If so, the criteria for identifying these 1.000 companies should be explained in more detail.

The search strategy presented on page 32 of the TPDE paper seems insufficient to uphold the above statement.

While an independence screen was performed (using BvD independence indicator above A- (A+, A, A-)) and a turnover threshold (> 2 million EUR) was applied, these rudimentary parameters cannot ascertain a homogenous set of comparables in the sense that transfer pricing practitioners usually refer to the homogeneity of functional profiles.

It seems pertinent to apply an additional screen for intangibles. It also seems appropriate to segment the pool of comparables based on turnover or to introduce a cap (maximal turnover) to account for the effects of size differences.

Ultimately, it needs to be ensured that the functional and risk profile is sufficiently “homogeneous” to sustain methodological consistency and to prevent a potential confusion between the risk profile of the comparables and the country risk as distinct factors.

Not observing this delineation would render any subsequent interpretation to be highly difficult. The relevant country risks are rated from AAA to B (comprising almost the entire rating scale), while all other factors (i.e., including the implied stand-alone ratings) of the potential comparables would need to be narrowly grouped between a few notches of the scale (presumably rather close to the AAA to AA due to their routine classification).

To qualify as homogeneous, the only (substantial) difference between the comparables should be the country-risk, which in turn would be the only variable explaining differences in profitability.

In other words, we need to ensure that we are limiting the scope of the analysis to low-risk distributors because including fully-fledged distributors would widen the default IQR and the effects of differing country risks would likely be exaggerated.

One additional observation regarding the country ratings is that TPED segments the rating classes into three groups: firms in countries with a sovereign rating of AAA or AA; firms in a country of sovereign rating A, and firms in a country of sovereign rating BBB, BB, or B.

In this context, the choice to group B together with BBB and B seems inconsistent with the financial data because country risk B seems to have a much more distinct correlation to profitability compared to BBB and BB.

The illustration of the effect of different functional and risk profiles provided by the OECD transfer pricing guidelines in 9.46 and 9.47 may serve also provide a sensible frame of reference.

The explanations offered by the OECD in this context would also serve as a plausible interpretation of Figure 1 [page 10] summarizing the TPDE results, namely the differing rating classes reflect a situation where a “[…] distributor is surrendering a profit potential with significant uncertainties [class B] for a relatively low but stable rate of profitability [class AAA]”.

As illustrated by the OECD, whether an independent party would be willing to accept such a tradeoff, will ultimately depend on the anticipated return under both scenarios, and on its level of risk tolerance. Whether additional compensation would be required in such a case must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Again, this interpretation seems to be consistent with the general position adopted by the TPED [p.17], which should be explicitly applied to the interpretation of Figure 1 as well.

In sum, the argument for a default adjustment does not seem strong (with the possible exception to class B risks). Here the presentation of the empirical results should be extended, and the empirical results [p.35/36] should be linked more explicitly to the interpretation of Figure 1.

The respective interpretation should also address the “translation” from statistics to transfer pricing – i.e., will a (any) statistically significant difference translate to the requirement of a compensating adjustment – or is it feasible to limit the requirement to a really great difference (i.e., how many notches are significant for transfer pricing purposes)?

One additional interpretation to be derived from Figure 1 seems to be the correlation between country risk and profitability.

For categories AAA to BBB [i.e., the investment grades] the difference seems non-existent (negligible). Now, if the only substantial difference relates to class B risk, the question arises whether the TPED should more appropriately be contextualized with quantifying (partially) the so-called “location-specific advantages” instead of seeking to provide a general analytical framework for calculating baseline rates.

Looking at the initial evidence presented by the TPED, it would at least seem sensible to think about contextualizing the country-risk analysis with the location-specific advantages concept (or commenting on differences), which would have the advantage in embedding the recommendations in the existing OECD transfer pricing guidelines.

In sum, the regression analysis seems to support the hypothesis formulated by TPED that accounting for country risk is plausible and relevant for the transfer pricing practice, especially as an additional justification for selecting foreign comparables.

It seems sensible, and is highly welcome, to promote a more flexible approach to selecting comparables; i.e., advocating the pragmatic South African approach as a sort of best practice.

In terms of policy recommendations, it seems to follow that tax administrations must be convinced of the validity of this approach.

It is unclear whether comparing these findings with the use of pan-regional benchmarks is likely to facilitate consensus in this respect.

The priority should be on stressing the principle of proportionality and allowing both approaches, pan-regional studies as well as a country-risk based approach (as step 3 and step 4 of the analytical framework proposed by TPED).

Both approaches should be accepted by tax authorities pursuant to the OECD transfer pricing guidelines 3.33 (see above).

Promoting the proposed framework

In sum, the analytical framework outlined by the TPED in Section 4.1. and the decision tree illustrated in Figure 4.2 of the TPED paper appear highly sensible.

As described above, the implementation of the process outlined in Figure 4.2. is already feasible on the basis of existing OECD transfer pricing guidance.

From the perspective of MNEs (and consultants), the outlined process is likely to be readily accepted. The obstacle will be convincing tax authorities. It may be beneficial, in terms of adopting a streamlined communications strategy, to emphasize that the process is aligned with existing OECD guidance (if not “in letter,” certainly “in spirit”).

The degree of “novelty” of the proposed analytical framework should, however, not be emphasized unnecessarily, as this is likely to confuse the discussion.

Arguably more important would be emphasizing that adjustments to differences in country-risk would only apply in step 4 of the outlined process. Initial reactions to proposed adjustments based on a rather complex technical method may be somewhat “reserved.”

This could also be facilitated when driving the case study to its logical conclusion, i.e., actually performing a manual screening.

Based on the data provided in Table 1, it would be reasonable to assume that there will often be no reason to perform step 4 at all, as step 3 ensures a sufficient number of potential comparables (> 400) that will allow identification of an appropriate number of reliable comparables.

It should also be addressed that in the case at hand, the pan-African search (step 2) would also have to be pursued.

While the number of potential comparables is admittedly very small, it may be feasible to identify at least a couple of sufficiently reliable comparables.

Again, from a policy perspective, the principle of proportionality would have to be stressed. In case of a high-risk transaction (high volume), step 2 will likely not be satisfactory, but for small transactions (SMEs), it could well be sufficient, and the administrative burden (costs) of a more complex analysis could be avoided.

Generally, the pragmatic mindset adopted by TPED appears commensurate with the OECD position. Specifically, acknowledging that “[…]the country risk adjustments […] will not necessarily be perfect, but their imperfection should not be a reason for their disqualification” [p.18] is sensible here.

The corresponding cautioning stance of the TPED is reasonable, namely “the application of corporate finance theory to transfer pricing needs to be well framed and implemented.” [p.18].

In this context, the TPED briefly addresses the case of a toll manufacturer which, due to “protection” by the group (principal), is not exposed to the same risks as other local market players while still being subjected to some systemic risk stemming from operating in a specific country [p.19].

Again, this point (segmentation or delineation of country-risk) requires elaboration before being used in the analytical framework.

It is also important to contextualize the analytical framework with paragraphs 3.47 and 3.50 to 3.52 of the OECD transfer pricing guidelines.

Especially, OECD transfer pricing guidelines 3.47, defining an appropriate degree of comparability and anchoring principle of proportionality, seems sensible and should be appropriately reflected in the framework:

“To be comparable means that none of the differences (if any) between the situations being compared could materially affect the condition being examined in the methodology or that reasonably accurate adjustments can be made to eliminate the effect of any such differences. Whether comparability adjustments should be performed (and if so, what adjustments should be performed) in a particular case is a matter of judgment that should be evaluated in light of the discussion of costs and compliance burden.”

Here the TPED study is helpful in illustrating that adjustments for country risk can be required in cases when, due to the lack of available domestic comparables, the scope of the comparability is extended to countries with significantly different risk profiles.

The scope of adjustments for country risk would thus likely be limited to step 4 of the proposed framework, while comparability analyses performed based on steps 1 through 3 should not require these adjustments.

Further, OECD transfer pricing guidelines 3.50, on clarity regarding the purpose of comparability adjustments states:

“Comparability adjustments should be considered if (and only if) they are expected to increase the reliability of the results. Relevant considerations in this regard include the materiality of the difference for which an adjustment is being considered, the quality of the data subject to adjustment, the purpose of the adjustment and the reliability of the approach used to make the adjustment.”

Again, applied to comparability adjustments for country-risk, this would likely support adjustments in the context of step 4 of the proposed framework, while the necessity for adjustments on earlier steps (e.g., step 3) will be rather low.

Further, OECD transfer pricing guidelines 3.51 / 3.52 on avoiding making adjustments for the sake of making adjustments provides:

“Some differences will invariably exist between the taxpayer’s controlled transactions and the third party comparables. A comparison may be appropriate despite an unadjusted difference, provided that the difference does not have a material effect on the reliability of the comparison. On the other hand, the need to perform numerous or substantial adjustments to key comparability factors may indicate that the third party transactions are in fact not sufficiently comparable[…]. Likewise, sophisticated adjustments are sometimes applied to create the false impression that the outcome of the comparables search is “scientific”, reliable and accurate.”

These issues should generally be more stringently observed by the TPED in refining the analytical framework.

Again, this strongly supports limiting the comparability adjustments to step 4 of the proposed framework – which perhaps should be emphasized more clearly by the TPED.

The proposed calculations of country risk adjustments [section 5.3.] generally seem sensible. Whether country risk premiums are to be applied will likely also depend on the availability of the required data – again, the existing OECD guidance illustrated above would seem to provide a sensible general framework.

On a general note, the respective calculations are only the last step of the comparability analysis. First and foremost, we need to ensure that the earlier stages of the comparability analysis (notably the manual screening process) are adequately performed by capitalizing on the enlarged pool of potential comparables resulting from the widening of the search strategy.

In other words, it needs to be ensured that the food processing service provider operating in the UK which has been identified as a comparable indeed exhibits a functional and risk profile that matches that of the tested party operating in Ghana (see, for example, TPED on p. 21).

Failing to appropriately and explicitly contextualize the performance of comparability adjustments would threaten to dilute and misguide the general public discussion on benchmarking and especially the current discussion on baseline returns in the OECD Pillar 1 proceeding (see below).

Misguided policy recommendations

While the elements of the TPED paper have been praised above, the policy recommendations advanced by the TPED in section 6 of their paper require a more critical comment concerning the general application of the arm’s length principle.

The TPED argues that the empirical analysis of country-risk effects could be replicated to other (generic) functions and/or industries and help set fixed returns for certain “baseline” activities (so-called Amount B), as recently suggested by the OECD under the Pillar 1 proposal for the taxation of the digital economy.

It is clear that the OECD Pillar 1 approach, which is based on arbitrary baseline remunerations, is lacking an economic rationale and that there is ample room for improvement.

In coping with the Pillar 1 approach, the discussion on quantifying the baseline remuneration is, however, only scratching the surface of the issue.

In a nutshell, Pillar 1 reflects an extremely worrisome development that erodes the application of the arm’s length principle by proposing a (partial) substitution with formulary apportionment.

The context of Pillar 1 is, thus far, limited to the digital economy and introducing a new nexus (Amount A) and how market states can share in the synergies realized by an MNE “beyond” mere baseline activities (Amount B).

The premise of the OECD under Pillar 1 is that the arm’s length principle, at least in its present form, cannot ensure that these objectives can be met, hence the introduction of formulary apportionment elements.

One aspect for driving the OECD Pillar 1 proposal is a (perceived) dissatisfaction with the challenges of conducting arm’s length based transfer pricing.

But this is arguably not the key issue – at least it should not be. The conflict between the market and non-market states is not so much whether a routine remuneration can adequately be calculated (and maybe “uplifted” for developing countries), but rather whether the market-states should be entitled to share in synergies (i.e., the residual profits) resulting from integrated operations in the digital economy.

In other words, the Pillar 1 discussions are focused on an entirely different conceptual issue. It is unclear whether TPED is aware of these differences. The fact that their paper has a different title form their framework paper would suggest that they are aware.

It is not helpful for the debate that the TPED presents a neutral view on the arm’s length principle in the context of the framework paper, while the empirical paper reflects a distinctly more skeptical stance; i.e., stating that “In the absence of uniform guidelines on the optimal identification for comparable companies, however, it remains a concern that poor selection choices may lead to biased estimates, which in turn may systematically bias international revenue flows” [TPED paper p.27].

In my perception, the TPED framework paper did not claim or demonstrate biased estimates or international revenue flows.

It is also quite different to say that “[a]vailable transfer pricing guidelines, notably the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines or the U.N. Transfer Pricing Manual, do not necessarily provide a strict position on the usage and adjustment of foreign comparables” [p.7. – framework paper] opposed to claiming that “This practice is not well-defined and, to our knowledge, there does not exist universal guidelines on where to find foreign comparable companies, how to specify them and how to identify the necessity of adjustment” [p.28 – empirical paper]. The latter seems somewhat exaggerated (as steps 1 -3 of the framework, shown above, are well established).

There is no doubt that the TPED approach would be suited to calculate baseline remunerations that make more economic sense than those arbitrarily stipulated by the OECD.

But, regrettably, that is not an impressive achievement. The policy implications thus seem detrimental, as the TPED recommendations seem aimed at legitimizing the adoption of the Pillar 1 proposal (Amount B), not just for the digital economy, but for all business models.

Linking the sensible TPED proposal on accounting for country risk in benchmarking to the highly controversial OECD Pillar 1 proposal seems completely unnecessary and, to a certain degree, inconsistent.

If anything, the TPED paper, as shown above, demonstrates that pragmatic solutions for applying the arm’s length principle can be found for developing countries.

Not only does it seem that the TPED proposal is suited to promise a fruitful discussion on the acceptance of nondomestic comparables, it also implies that tested parties located in high-risk countries (developing countries, which would largely coincide with the market states supporting Pillar 1) would receive a higher remuneration compared to the status quo (which fails to systematically account for country-risk adjustments).

Communicated in a coherent and straightforward manner, these two effects inherent in the TPED proposal should make finding a consensus on the proposed framework possible. The analysis presented by the TPED could thus strongly support advocating to sustain a framework embedded in the existing arm’s length based OECD transfer pricing guidelines.

As such, TPED could facilitate strengthening the consensus on the application of the arm’s length principle rather than sponsoring policy recommendations, which potentially erode the increasingly fragile consensus.

This is not to say that simplifications for transfer pricing are not desirable or feasible. But, from a policy perspective, it would be preferable to contextualize respective recommendations with safe harbor provisions (akin to the mark-up on centralized low-value-added services – Chapter VII, Section D of the OECD transfer pricing guidelines) and stay away from Pillar 1.

Be the first to comment