By Allan Lanthier, Montreal, retired partner of an international accounting firm and former advisor to the government of Canada

On December 20, 2021, the OECD issued model rules for Pillar Two—the 15% global minimum tax. It is a brutally complex 70-page package and introduces two fundamental changes to the October 2021 OECD framework: a new Qualified Domestic Minimum Top-Up tax (QDMTT) and a significant rewrite of the Undertaxed Payment Rule (UTPR).

Close to 140 countries agreed to the October 2021 framework, but not to these new model rules. The changes introduce even more uncertainty and complexity to Pillar Two. In addition, the new UTPR may violate many bilateral tax treaties. Pillar Two is starting to look more like a train wreck than a coherent set of rules.

The new domestic top-up tax

Under the October 2021 framework, there were two steps. First, the Income Inclusion Rule (IIR) imposed a top-up tax on the Ultimate Parent Entity (UPE) in respect of low-taxed income of a foreign subsidiary. Second, if the IIR did not apply (because the country of the UPE had not enacted Pillar Two), the UTPR denied deductions on base-eroding, intragroup payments made to entities in the low-taxed country (more on the UTPR later).

In an astonishing development, the model rules created a third alternative—the QDMTT. Under this new rule, low-taxed countries—the countries that have long helped large corporations avoid tax—are now first in line to charge the top-up tax on low-taxed income of entities in that country. These countries do not have to increase their general corporate income tax rate: In fact, they can collect the top-up tax even if they have no corporate income tax at all. And why wouldn’t they impose the tax? After all, the country of the UPE will charge the tax if the QDMTT is not adopted.

Switzerland was one of the first countries out of the gate. Swiss Finance Minister Ueli Maurer announced that Switzerland intends to adopt the QDMTT. “If 15% is going to be levied, then we want to levy that in Switzerland,” several news outlets quoted him as saying at a January news conference in Bern. Around 2,000 Swiss subsidiaries of foreign parents will be affected by the move. The countries where the UPEs are located won’t receive a dime. Other countries have followed suit.

Why should MNEs care which country charges the top-up tax? Well, consider a simple structure where the UPE is in the U.S., and owns 100% of a foreign subsidiary in a low-taxed country. The foreign country enacts the QDMTT. Even if the Biden administration makes sufficient headway for global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) to be considered compliant with Pillar Two, it is uncertain whether the U.S. will grant foreign tax credits. If not, the result is double taxation: The low-taxed income is taxed to the UPE under GILTI and to the foreign subsidiary under QDMTT, with no relief mechanisms.

The undertaxed payment rule

The new UTPR is even more problematic. The UTPR acts as a backup to the IIR (and now to the QDMTT as well). Under the October 2021 framework, the UTPR was an undertaxed payment rule: Additional tax was to be levied by denying deductions for intragroup payments to low-taxed group entities. But the rule is now radically different.

Under the model rules, any additional tax that is not captured as top-up tax (under the IIR or QDMTT) is allocated as additional tax to group entities based on the relative number of employees and relative book value of tangible assets in each adopting country. In other words, a group entity in a UTPR jurisdiction may be charged tax on income with which it has no nexus whatever.

What is the mechanism for charging the tax? The model rules suggest that domestic tax law should simply deny otherwise deductible expenses up to the amount required to yield the additional amount of cash tax determined by the formula.

In summary, a country will tax income that is neither earned by one of its residents nor sourced in that country. Here’s a simple example.

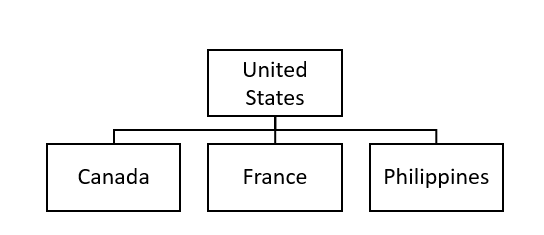

US Parent owns 100% of subsidiaries in Canada, France, and the Philippines (Co. P). Assume that neither the U.S. nor the Philippines is part of Pillar Two (the U.S. because GILTI is not considered compliant). As a result of deductions and credits, US Parent and Co. P have paid tax of less than 15% under the Pillar Two rules. The subsidiary companies in Canada and France must, therefore, pay additional tax under the UTPR on income earned by US Parent and Co. P.

Houston, we have a problem. The United States and the Philippines have tax treaties with Canada and France, and the imposition of tax under the UTPR by Canada and France is inconsistent with those treaties. For starters, article 7 of the treaties only allows a contracting state to tax business profits if a business is carried on in that state through a permanent establishment. Article 9 of the treaties (associated enterprises) also appears problematic, as does the non-discrimination article.

The OECD stated that its October 2021 framework was compatible with existing tax treaties. That no longer seems accurate, and so yet another multilateral tax convention may be required to accommodate the new UTPR. Without another multilateral instrument, companies that are taxed under a domestic UTPR regime may well challenge the validity of the tax in court. In short, the fate of Pillar Two seems uncertain.

What race to the bottom?

Even before these two changes, the Pillar Two framework created massive complexity and uncertainties. Others have commented on them. This was all necessary, proponents argued, to address the “race to the bottom.” But what race is that exactly? Corporate statutory rates have decreased over the last several years, but there have been base-broadening measures, as well. And, except for the United States, corporate tax has been rising as a percentage of GDP in most countries for almost 50 years.

For example, based on OECD data, Canada’s corporate tax-to-GDP ratio increased by 26% from 1972 to 2019. The ratio increased by 10% in the same period in the UK, and by 24% in Germany. And for the OECD on average, the increase was a whopping 48%.

With numbers like these, and a UTPR that appears to violate bilateral tax treaties in many countries, it is time to hit the emergency brake on Pillar Two. Government leaders around the world should consider a more balanced and sensible approach.

-

Allan Lanthier is a retired partner of an international accounting firm and former advisor to the government of Canada. He lives in Montreal. He thanks Jinyan Li, professor of law at York University in Toronto, for her insights on the UTPR and its interaction with tax treaties.

First, what is wrong with the QDMTT? It was always recognised that increasing resident country taxes and giving a credit increases the ability of source countries to impose tax. Not just Switzerland and other hubs, but any country where there is excess income.

Second, the October Blueprint did not specify how the UTPR would work – just that there would be one. Using payments to low tax countries as the allocation method was extremely complex – the Model Rules allocation method is much simpler.

Third, if CFC taxes are treaty compliant, it is difficult to see a problem with the UTPR. The UTPR recognises the reality of corporate groups. The inconsistency with a broad interpretation of article 7 is obvious, and so the 137 countries that agreed the Model Rules must be taken to have agreed that article 7 is no longer appropriate to that extent.

Casey, thank you for these comments. They help contribute to a constructive debate on Pillar Two.

First, there is nothing necessarily wrong with the QDMTT. However, it did not form part of the October Blueprint – the document that IF participants actually agreed to. At that time, the OECD stated that model rules would be developed “to enhance consistency and improve rule co-ordination”. In my view, the model rules were expected to give effect to – not replace – the GloBE rules. As for complications, we now have potential double taxation for example for US headquartered groups (even if GILTI becomes compliant) unless additional credit rules are introduced.

On UTPR, the October Blueprint was detailed and explicit – in fact there was an entire chapter devoted to UTPR. And the details in that chapter were consistent with the 2019 work program and the January 2020 statement. The formulary apportionment now included in the model rules with no nexus whatever is extraordinary – it represents a fundamental departure from the century-old principle of taxation based on either source or residence.

Third, who knows if CFC taxes are treaty compliant, unless of course the relevant treaty explicitly says so (as many of Canada’s treaties do). The OECD says that this is for greater certainty (in which case the treaty drafters have spoken in vain I suppose). In the coming years, we shall see what the courts have to say in many countries as taxpayers challenge assessments under UTPR and perhaps under the IIR as well.