By Noopur Trivedi and Jitesh Golani

Out of the multiple crucial design elements of the global minimum tax under Pillar Two of the OECD/G20 July 1 statement, the adoption of “jurisdictional blending” for computation of effective tax rate and consequent top-up tax denotes one of the most pivotal policy choices for the global anti-base erosion (GloBE) rules. Given that the release of the final package is at a striking distance, this write-up intends to be an analytical dissection of this crucial policy component.

The article first discusses the concept of jurisdictional blending and the various choices that were available before the OECD. The article then discusses the contours of jurisdictional blending approach, including the identification of constituent entities, their base jurisdiction, assignment of income, and covered taxes. This is followed by a hypothetical case study culminating application of all concepts. Before concluding, the article deliberates on whether jurisdictional blending decimates profit-shifting practices entirely.

The release of the OECD/G20 July statement on the two-pillar solution puts the final nail in the coffin to all speculations around the implementation of the global minimum tax proposal. At the time of writing this article, 134 members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework have agreed on the critical policy design of Pillar One and Pillar Two. Of these two pillars, the latter has a far-reaching impact as it targets a wide array of multinational enterprise groups with consolidated revenues over EUR 750 million (approximately USD 880 million).

Jurisdictional blending under the GloBE policy

The objective of the GloBE policy is to ensure that multinationals pay a minimum level of tax on their profits regardless of their headquarters or location, and thus, put a full stop on jurisdictions’ unsustainable race to rock-bottom taxes. The levy of the global minimum tax requires a comparison between the effective tax rate of multinational groups with the GloBE tax rate (currently a minimum of 15%).

During policy formulation for GloBE rules, several proposals were floated for computation of effective tax rate, namely worldwide blending, jurisdictional blending, or entity blending. The US global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) regime applies the 90% high tax exemption based on a more granular ‘tested unit’ concept and applies the worldwide blending for low-taxed income of balance tested units (although the provision is in the midst of potential reform).

For the GloBE rules, while the broad-based worldwide blending could have been simpler to comply with and administer, it may not be an appropriate measure to counter tax competition. At the same time, the granular entity-level approach could have been a nightmare for stakeholders, and also beyond the GloBE policy objectives, which was never to put an entity-wise floor rate. With the jurisdictional blending approach, the GloBE rules seek to achieve the best of both worlds.

Under the jurisdictional blending approach, the GloBE tax liability will arise when the effective tax rate of a particular jurisdiction (including the stateless jurisdiction, as we will see later) in which the multinational group operates is below the GloBE minimum rate. Though it may sound simple, the jurisdictional effective tax rate computation involves a series of steps, with each step governed by a web of intricate rules.

The determination of jurisdictional effective tax rate under the GloBE rules broadly involves three steps (although there are several other concepts affecting computation that are beyond the scope of this article). The first step is identifying the constituent entities and their base jurisdiction. The second is assigning income and covered taxes to each jurisdiction. The third is computing the jurisdictional effective tax rate.

Identification of the constituent entities and their base jurisdiction

The OECD blueprint defines the term “constituent entity” as any separate business unit that is a part of consolidated financial statements for financial reporting purposes, including those ignored solely on the grounds of size or materiality. Further, a permanent establishment of any separate business unit would be a separate constituent entity, provided the business unit prepares separate financial statements for financial reporting, regulatory, tax reporting, or internal management control purposes for such permanent establishment. This definition majorly aligns with the country-by-country reporting rules. The entities excluded from the GloBE rules ambit (such as pension funds, government entities, investment funds) are not constituent entities.

An essential prerequisite for the computation of jurisdictional effective tax rate is identifying the jurisdiction to which income and taxes of a constituent entity should be assigned. As a thumb rule, a constituent entity is tagged to the jurisdiction where it is liable for covered tax on its income based on the place of management, place of incorporation, or similar criteria (that is, basis its tax residence).

There are some exceptions to this thumb rule for special cases. A permanent establishment, which is a constituent entity, is tagged to the jurisdiction of its location. A constituent entity that is a separate taxable entity in its jurisdiction but fiscally transparent in its owner’s jurisdiction (i.e., hybrid entity) is assigned to the jurisdiction of its tax residence. A constituent entity that is a fiscally transparent entity in its owner’s jurisdiction and the jurisdiction of its incorporation is tagged to the “stateless” jurisdiction. Similarly, a constituent entity that is fiscally transparent in its jurisdiction but a taxable entity in its owner’s jurisdiction (reverse hybrid) is also tagged to the “stateless” jurisdiction. Further, a constituent entity located in a jurisdiction that does not levy corporate income tax is tagged to the jurisdiction of its creation, except if the entity is liable for income tax on a residence basis in another jurisdiction due to control and management criteria.

Assigning income to jurisdictions

The rules for the assignment of income are pretty straightforward as the income flows to the base jurisdiction, determined as per the above rules (including stateless entities and permanent establishments). An exception to this principle is allocating income and expenses of fiscally transparent entities tagged to the stateless jurisdiction. In certain circumstances, the income of such entities can be allocated to the jurisdiction of the other constituent entities within the multinational group, primarily including the owner’s jurisdiction, which taxes the owner’s share of income, or the jurisdiction of the permanent establishment of the constituent entity/its owners.

Accordingly, the base jurisdiction of a fiscally transparent constituent entity could differ based on the treatment adopted by the owner’s jurisdiction. Consider the situation of a fiscally transparent entity held equally by two constituent entities wherein one of the owner jurisdictions considers the investee entity a separate entity, and the other treats it as fiscally transparent. In such a case, the income and taxes of the investee entity would partially get assigned to the owner’s jurisdiction and partially to the stateless jurisdiction. Further, if an owner of a stateless entity is itself a stateless entity, the rule applies to that owner’s share of the income as if that owner directly earned its share of the income.

Assigning covered taxes

Covered taxes generally follow the jurisdiction of the underlying income (including the stateless jurisdiction). There are several critical aspects concerning the allocation of covered taxes in the cross-border scenario.

Withholding taxes on royalties/interest imposed by source jurisdiction follow the jurisdiction where underlying income is assigned (i.e., generally residence jurisdiction). However, withholding taxes on dividends are assigned to the jurisdiction of the constituent entity declaring dividends (i.e., the source jurisdiction) unless covered by any targeted anti-avoidance rules (expected in the final package).

Taxes paid by the shareholder under a controlled foreign company regime are allocated to the controlled foreign company, following the underlying income included in controlled foreign company’s tax base.

Covered taxes arising from the sale of stock of a constituent entity are excluded from the jurisdictional effective tax rate computation to the extent the underlying gains do not form part of the GloBE tax base.

Covered taxes on passive income (e.g., royalties) paid in one jurisdiction but allocated to another jurisdiction could create possibilities for multinationals to shift income and associated taxes to low-tax jurisdictions to escape/reduce the top-up tax burden. Targeted rules could be expected in the final package to counter such tax avoidance practices.

Computation of the jurisdictional effective tax rate

The jurisdictional effective tax rate is derived by dividing the aggregate covered taxes assigned to a jurisdiction by the aggregate tax base assigned to that jurisdiction. If the aggregate tax base assigned to the jurisdiction is equal to or less than zero, there would be no liability under the GloBE rules for that year.

Understanding jurisdictional blending through hypothetical case study 1

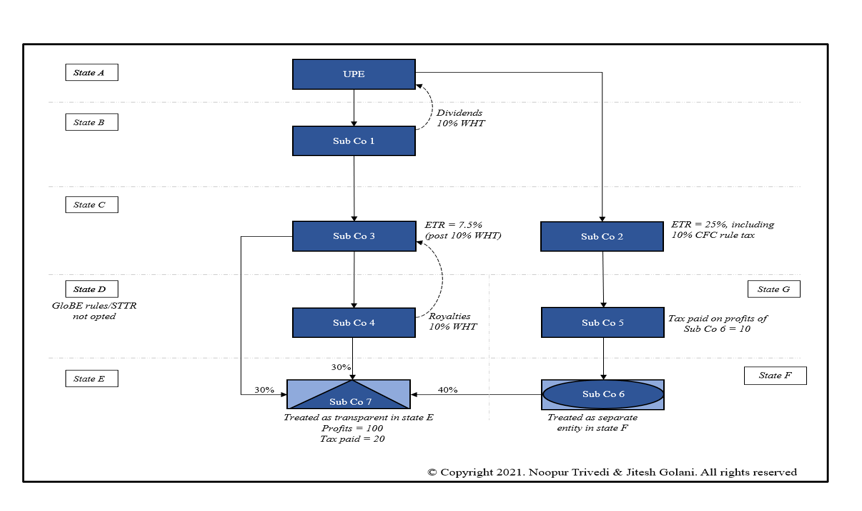

Consider a multinational group, headquartered in State A, that has subsidiaries across the globe. Apart from the apparent details depicted in the group structure below, assume several additional key facts.

State C’s tax law includes the controlled foreign company regime, pursuant to which Sub Co 2 pays controlled foreign company tax on the passive income of Sub Co 5. Post inclusion of controlled foreign company tax, the effective tax rate of Sub Co 2 increases from 15% to 25%.

Sub Co 6 is taxable in State F but fiscally transparent in State G. Accordingly, Sub Co 5 pays taxes in State G on the profits of Sub Co 6.

Sub Co 7 is a fiscally transparent entity in State E. However, the jurisdictions of its owners have distinct entity recognition rules. State C considers it a separate taxable entity, and thus, it does not levy any tax in the owners’ hands. State D treats it as fiscally transparent and taxes the owners on their share of income. State F also treats it as fiscally transparent. However, based on the E-F tax treaty, Sub Co 7 forms a permanent establishment of Sub Co 6 in State E, and proportionate profits (40%) are attributable to the permanent establishment. Sub Co 7 does not create a permanent establishment for Sub Co 3 and Sub Co 4 as per the concerned tax treaties.

Sub Co 3 licenses certain intangibles to Sub Co 4, in consideration of which it receives royalties. Sub Co 4 withholds taxes on the royalties at the rate of 5%. State D has not adopted the GloBE rules / subject to tax rule.

Sub Co 1 distributes dividends to its shareholder in State A after withholding taxes at the rate of 10%.

Group structure

Identification of the base jurisdiction

According to the thumb rule, the base jurisdiction of the ultimate parent entity, Sub Co 1, Sub Co 2, Sub Co 3, Sub Co 4, and Sub Co 5 are their respective tax jurisdictions, i.e., State A, State B, State C, State D, and State G.

Considering that Sub Co 6 is a hybrid entity, its base jurisdiction is State F.

Sub Co 7, being a fiscally transparent entity in State E, is tagged to the stateless jurisdiction.

Assignment of income and covered taxes to jurisdictions

Dividend: The underlying profits from which Sub Co 1 has paid dividends to the ultimate parent entity are part of the GloBE tax base of Sub Co 1. Accordingly, Sub Co 1 would include the withholding taxes on dividends in its effective tax rate computation.

Royalties: The GloBE tax base of Sub Co 3 includes royalty income, and correspondingly, Sub Co 3 also includes the withholding taxes on royalties while computing its jurisdictional effective tax rate in State C. The assignment of withholding taxes increases the overall effective tax rate of Sub Co 3 from 6% to 7.5%.

Controlled foreign company tax: Sub Co 2 pays tax in State C on the passive income of its controlled foreign company in State G. Since Sub Co 5 includes the underlying passive income in its GloBE tax base, its effective tax rate computation would include the corresponding tax paid by Sub Co 2. Accordingly, the effective tax rate of Sub Co 2 would reduce from 25% to 15%.

Income and taxes of Sub Co 6: The income and taxes paid by Sub Co 6 are allocable to State F. Thus, the effective tax rate computation of Sub Co 6 in State F would include the taxes of 10 paid by Sub Co 5 on the profits of Sub Co 6 in State G.

Income and taxes of Sub Co 7: State C considers Sub Co 7 as a separate taxable entity. Accordingly, the share of Sub Co 3’s income and covered taxes (30 and 6, respectively) are allocable to the stateless jurisdiction. State D considers Sub Co 7 as a fiscally transparent entity, and thus, the share of Sub Co 4’s income and covered taxes (30 and 6, respectively) are allocable to State D. Though State F considers Sub Co 7 fiscally transparent, the latter forms a permanent establishment of Sub Co 6 in State E. Thus, assuming Sub Co 6 prepares separate financial statements for the permanent establishment, the permanent establishment constituent entity’s income and covered taxes (40 and 8, respectively) would be assigned to State E.

Jurisdictional blending for Sub Co 2 and Sub Co 3: The effective tax rate of Sub Co 2 after excluding the controlled foreign company tax is 15%, whereas the effective tax rate of Sub Co 3 after including the withholding tax on royalties is 7.5%. Assuming equal weights/tax base for both entities, the jurisdictional effective tax rate would be a simple average of 15% and 7.5%, i.e., 11.25%. Further, suppose the GloBE minimum tax rate finalizes at 15%, Sub Co 2 and Sub Co 3 would classify as low-taxed constituent entities of the multinational group (though Sub Co 2 on a standalone basis is a high-tax constituent entity), and thereby subject to a top-up tax of 3.75%, allocable under the GloBE rules.

Jurisdictional blending and the profit-shifting concern

As elaborated above, one reason for non-adoption of the worldwide blending for the GloBE effective tax rate computation purposes could be to eliminate the possibility of a low-tax jurisdiction benefitting at the cost of high-tax jurisdictions. While the jurisdictional effective tax rate approach overcomes this shortcoming, the question arises as to how far this approach acts as an effective tool in combating profit-shifting practices. Let us evaluate this through a case study.

Hypothetical case study 2

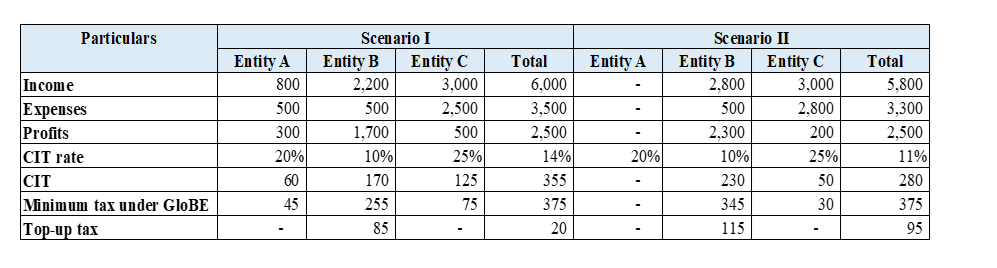

Consider a base case scenario (Scenario I) in which an in-scope multinational group has three subsidiaries, Entity A, Entity B, and Entity C in State A, State B, and State C, respectively. Entity A is the global services support center and renders services to Entity B and Entity C for a consideration of USD 500 and USD 300. The third-party expenditure incurred by Entity A for providing such services is USD 500. Entity B holds valuable intangibles of the group licensed to Entity C and receives royalty amounting to USD 2,200. State B is a low-tax jurisdiction with a corporate income tax rate of less than 15%. Entity C is a licensed manufacturer selling products to third-party customers in State C. Revenue from third-party customers is USD 3,000.

In addition, consider an alternative iteration of Scenario I with certain modifications (Scenario II). The operations of Entity A are shut down and taken over by Entity B. Consequently, Entity B records revenues of USD 300 from Entity C and third-party expenses of USD 500. State A does not have exit charge provisions in its tax law. Entity B assumes more functions/risks concerning intangibles, and thus, charges a higher royalty of USD 2,500 (as compared to 2,200 earlier).

Under Scenario I, based on the jurisdictional blending approach, the effective tax rate for the multinational group in State B is below the GloBE minimum rate of 15%, and thus, Entity B classifies as a low-taxed constituent entity leading to a top-up tax liability of USD 85. The total tax paid by the multinational group, post the top-up tax, is USD 440 (USD 355 + USD 85) under the jurisdictional blending approach, whereas the total tax remains USD 375 (USD 355 + USD 20) under the worldwide blending approach. At first glance, the jurisdictional blending approach achieves what it set out to achieve, i.e., eliminate effective tax rate blending of high-tax jurisdictions with low-tax jurisdictions and maximize the tax liability.

Now consider Scenario II wherein due to internal reshuffling in functional profile, the multinational group concentrates higher profits in Entity B, which results in a higher top-up tax of USD 115 but reduces the overall tax cost for the group to USD 395 (USD 280 + USD 115). Assuming the ultimate parent entity is a tax resident of a separate jurisdiction, the ultimate parent entity jurisdiction would enjoy higher top-up tax. However, State A would lose not only tax revenue but also foreign direct investment-linked economic benefits. Similar will be the outcome if the ultimate parent entity is a tax resident of State A.

The above illustration demonstrates that jurisdictional blending may not be able to entirely pull the curtains down as far as profit shifting is concerned – multinational enterprises may still be tempted to shift profits from high tax jurisdiction (> 15%) to low-tax jurisdictions and benefit from the tax rate arbitrage. In a way, the GloBE rules may provide a safe harbor to such profit-shifting practices that intend to take the shelter of the minimum tax rate of 15%. The worldwide blending approach could demotivate such profit-shifting practices (tax cost for the multinational group is equal in both scenarios), but this would result in lesser top-up tax collections for ultimate parent entity jurisdictions.

The OECD blueprint acknowledges the issue of profit shifting through the transfer of passive income and corresponding taxes to low-tax jurisdictions for circumventing GloBE tax liability. As a solution to such practices, the blueprint notes that targeted anti-avoidance rules should be developed as a part of the final package. However, the discussion in the blueprint is precisely in the context of preventing the shifting of high-tax passive income to shelter the low-taxed incomes in low-tax jurisdictions. The situation considered in the case study involves shifting of profits consequent to migration of functions and risks. Probably, the proposed anti-avoidance rules may not cover those cases where the realignment of functional profile amongst constituent entities is based on accepted transfer pricing principles. This could be the case even when the sole intent behind profit shifting is to lower the multinational’s global effective tax rate. Thus, the GloBE rules may not be a final nail in the coffin for profit shifting practices after all!

Conclusion

The article briefly navigates through one policy element of GloBE, which in turn is a gamut of intricate rules. The case study on identifying jurisdictions under GloBE dwells over a stylized structure involving only a handful of entities. The fact pattern could be much more complicated for multinational enterprises having myriad web-like group structures in the practical world. Especially, divergent entity recognition rules in various jurisdictions could magnify the complexity associated with the jurisdictional blending.

Another intriguing aspect would be the impact of the GloBE policy on the corporate income tax rates. There is a lot of concern in low-taxed jurisdictions around the GloBE minimum tax rate of 15% as it undermines their tax sovereignty and pressures them to increase their corporate income tax rates. However, there should also be concern in high tax jurisdictions as the GloBE policy may still leave some room for profit shifting practices. If these jurisdictions do not want to lose on non-tax economic benefits linked to foreign direct investment, they may still be compelled to lower their corporate income tax rates to the minimum rate (as loss of some tax revenue could be inevitable). Presently, the statutory corporate income tax rates of certain major economies hover around 25%, allowing a trade-off of tax revenues with foreign direct investment. To summarize, while it may be true to say that GloBE prevents the race to the unfathomable bottom, in all probability, it can start the race to a new bottom of 15%.

— Noopur Trivedi and Jitesh Golani are international tax professionals-cum-researchers, based in India.

The views and opinions expressed are personal. The authors graciously invite any comments from readers at [email protected] to discuss and debate this intriguing international tax reform.

Be the first to comment